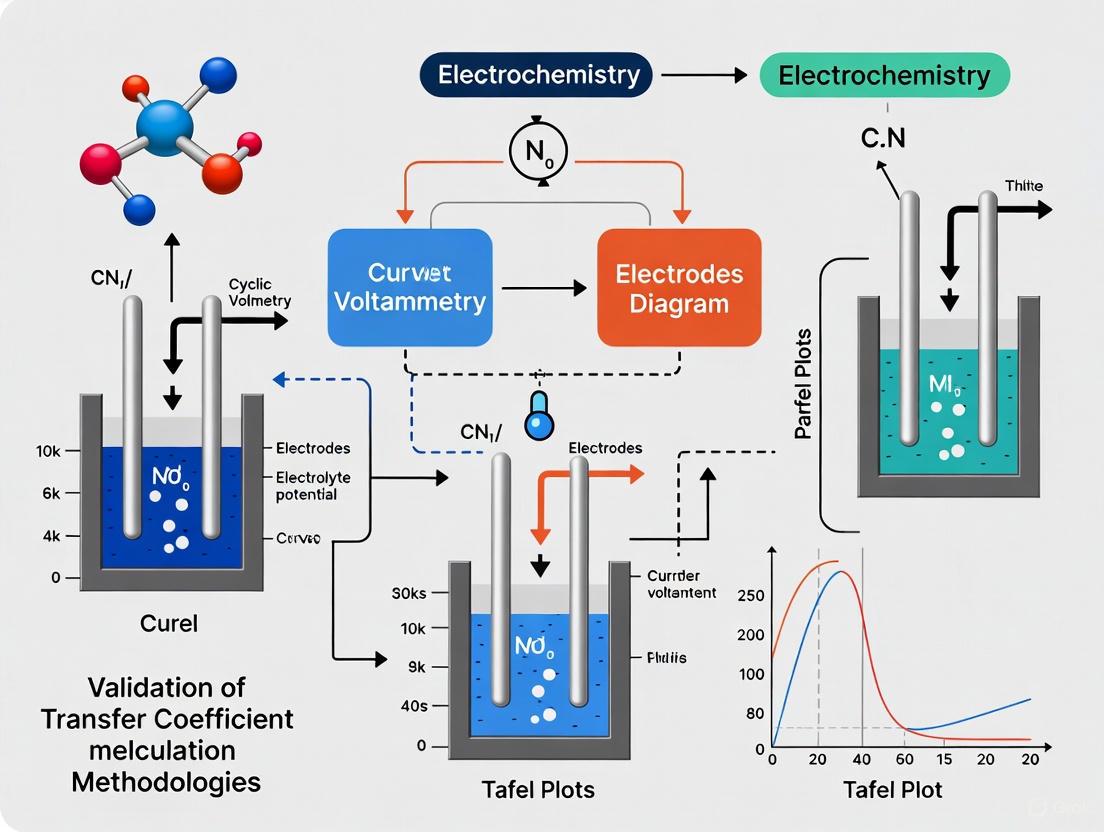

Validating Transfer Coefficient Calculation Methodologies: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical Research and Development

This article provides a systematic framework for the validation of transfer coefficient calculation methodologies, a critical process in pharmaceutical research and drug development.

Validating Transfer Coefficient Calculation Methodologies: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical Research and Development

Abstract

This article provides a systematic framework for the validation of transfer coefficient calculation methodologies, a critical process in pharmaceutical research and drug development. It addresses the foundational principles of transfer processes, explores advanced computational and empirical methodological applications, discusses common challenges and optimization strategies, and presents robust validation and comparative analysis techniques. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current best practices to ensure the accuracy, reliability, and regulatory compliance of transfer coefficient data, which underpins critical decisions from analytical method transfer to pharmacokinetic prediction.

Understanding Transfer Coefficients: Core Concepts and Regulatory Significance in Pharma

In bioprocess engineering, ensuring optimal environmental conditions within a bioreactor is paramount for cell growth, viability, and product yield. Two parameters are fundamental to this control: the volumetric mass transfer coefficient (kLa), which quantifies the efficiency of oxygen delivery from the gas phase to the liquid culture medium, and the heat transfer coefficient (HTC), which governs the rate of heat removal from the system [1] [2]. Efficient management of oxygen transfer and heat generation is critical for successful scale-up and commercialization of biopharmaceuticals. Within the context of validating transfer coefficient calculation methodologies, a clear understanding of both coefficients—their definitions, measurement techniques, and influencing factors—enables researchers and scientists to design more reproducible, scalable, and robust bioprocesses. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two pivotal parameters, supporting informed decision-making in drug development and manufacturing.

Theoretical Foundations: Defining the Coefficients

Volumetric Mass Transfer Coefficient (kLa)

The kLa is a combined parameter that describes the efficiency with which oxygen is transferred from sparged gas bubbles into the liquid broth of a bioreactor [1] [3]. It is the product of the liquid-side mass transfer coefficient (k~L~) and the specific interfacial area available for mass transfer (a) [4]. The oxygen transfer rate (OTR) is directly proportional to kLa and the driving force for transfer, which is the concentration gradient between the saturated oxygen concentration (C*) and the actual dissolved oxygen concentration (C) in the liquid [5] [3]. This relationship is expressed as:

OTR = kLa · (C* – C) [5]

The kLa value is influenced by numerous factors, including agitation speed, gassing rate, impeller design, and the physicochemical properties of the culture medium, such as viscosity and presence of surfactants [1] [3] [6].

Heat Transfer Coefficient (HTC)

While the search results provide less specific detail on the heat transfer coefficient (HTC) in bioprocessing compared to kLa, it is a parameter that quantifies the rate of heat transfer per unit area per unit temperature difference. In a bioreactor, significant metabolic heat is generated by cultivating cells, and this heat must be removed to maintain a constant, optimal temperature for the culture. The HTC defines the efficiency of this heat removal, typically through a jacket or internal coil. One study estimated solids-air heat transfer coefficients in a pilot packed-bed bioreactor, highlighting that such coefficients are essential for accurate modeling and scale-up, as it is not possible to assume the solids and air phases are in thermal equilibrium [2]. The heat transfer rate is generally governed by an equation analogous to that for mass transfer:

q = U · A · ΔT

Where q is the heat transfer rate, U is the overall heat transfer coefficient (HTC), A is the surface area for heat transfer, and ΔT is the temperature difference driving force.

Methodological Comparison: Experimental Determination Protocols

A critical aspect of validating calculation methodologies is the consistent application of robust experimental protocols. The methods for determining kLa and HTC differ significantly, reflecting their distinct physical phenomena.

Standard Protocol for Measuring kLa: The Dynamic Gassing-Out Method

The most prevalent technique for determining kLa is the dynamic gassing-out method, a physical method that is easy to use and provides accurate measurements without the need for hazardous chemicals or organisms [3] [4]. The following workflow outlines the key stages of this protocol, and Table 1 details the specific materials required.

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions for kLa Measurement

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Bioreactor System | Provides a controlled environment (temperature, agitation, gassing) for the measurement [4]. |

| Polarographic DO Sensor | Measures the dissolved oxygen concentration dynamically during the re-aeration step [4]. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | A standardized liquid medium that closely represents cell culture conditions, avoiding the variability of complex media [4]. |

| Nitrogen Gas (N₂) | Used to deoxygenate the liquid medium at the beginning of the protocol [4]. |

| Compressed Air | Used as the oxygen source during the re-aeration phase of the experiment [4]. |

| Thermal Mass Flow Controller | Ensures accurate and precise control of the gassing rates into the bioreactor [4]. |

The protocol involves several key phases. First, the dissolved oxygen (DO) sensor must be calibrated, typically at the process temperature (e.g., 37°C), by setting the 0% point when sparging nitrogen and the 100% point when sparging air [4]. Next, the liquid is deoxygenated by sparging with nitrogen at a high flow rate until the DO drops below 10%. A crucial step for cell culture bioreactors, where headspace effects are more significant, is purging the headspace with air to displace residual nitrogen. Finally, submerged gassing with air is initiated at the desired flow and agitation rates, and the increase in DO is recorded until it stabilizes above 90% [4].

The kLa is calculated by plotting the natural logarithm of the driving force against time. The data between 10% and 90% DO is used for a linear fit, the slope of which equals -kLa [1] [4]. The equation used is:

ln [ (C* – C(t)) / (C* – C₀) ] = –kLa · t [1]

Approaches for Estimating Heat Transfer Coefficient (HTC)

Based on the available search results, a standard protocol for HTC in stirred-tank bioreactors is not detailed. However, one methodology for estimating solids-air heat transfer coefficients in a pilot packed-bed bioreactor involves using temperature data obtained at different bed heights during drying, cooling, and heating experiments [2]. The solids-air heat transfer coefficient is then used as a fitting parameter to adjust a heat and mass transfer model to the experimental temperature data [2]. This indicates that determining HTC often involves inverse modeling from experimental temperature profiles rather than a direct dynamic measurement like the gassing-out method for kLa.

Comparative Analysis: Key Parameters and Optimization

Factors Influencing kLa and Optimization Strategies

The kLa value is highly sensitive to a wide range of process and system variables. Understanding these is key to optimizing oxygen transfer.

Table 2: Factors Affecting kLa and Common Optimization Strategies

| Factor | Effect on kLa | Optimization Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Agitation Speed | Increases kLa by improving mixing, reducing bubble size, and increasing interfacial area 'a' [3] [6]. | Increase speed within limits imposed by shear stress on cells [6]. |

| Aeration Rate | Increases kLa by providing more gas bubbles and surface area [3]. | Increase gas flow rate; balance against potential foaming [3]. |

| Impeller Design | Impellers designed for gas dispersion can significantly increase 'a' by creating smaller bubbles [6]. | Use impellers optimized for gas-liquid mixing (e.g., Rushton turbines, hollow blades) [6]. |

| Gas Sparger Design | Determines initial bubble size; smaller bubbles from fine-pore spargers increase 'a' and residence time [3] [6]. | Use spargers that produce a fine bubble size distribution [6]. |

| Antifoaming Agents | Typically reduce kLa by increasing bubble coalescence and reducing interfacial area [1]. | Use at minimal effective concentrations to mitigate negative impact. |

| Medium Viscosity | Higher viscosity reduces kLa by increasing resistance to diffusion and bubble breakup [6]. | Adjust medium composition to lower viscosity if possible [6]. |

| Temperature | Affects oxygen solubility (C*), physical properties of the liquid, and thus kL [3]. | Control at optimal for cell growth, recognizing the trade-off with solubility. |

Quantitative kLa Data from Experimental Studies

The following table summarizes typical kLa values obtained under different operating conditions, providing a reference for researchers.

Table 3: Experimental kLa Data from a BioBLU 1c Single-Use Bioreactor [4]

| Impeller Tip Speed (m/s) | Gassing Rate (sL/h) | kLa Value (h⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 5 | 2.33 ± 0.28 |

| 0.5 | 10 | 3.40 ± 0.33 |

| 0.5 | 25 | 5.39 ± 0.38 |

| 0.5 | 60 | 9.79 ± 0.24 |

| 0.1 | 25 | 1.89 ± 0.06 |

| 1.0 | 25 | 11.44 ± 0.47 |

Factors Influencing Heat Transfer Coefficient (HTC)

While data is limited, the search results indicate that the solids-air heat transfer coefficient in a packed-bed bioreactor is one of the key parameters for modeling, alongside the mass transfer coefficient and air flow rate [2]. A sensitivity analysis from that study suggested that predicted temperature profiles were more sensitive to the air flow rate than to the heat and mass transfer coefficients themselves, though it remained essential to model the phases separately using driving forces [2]. In more common stirred-tank bioreactors, the HTC (U) is generally influenced by the properties of the broth, the jacket coolant, the material and thickness of the vessel wall, and fouling on the heat transfer surfaces.

Application in Scale-Up and Process Validation

The reliable scale-up of bioprocesses is a major challenge in biopharmaceutical development. Both kLa and HTC play vital, though distinct, roles in this endeavor.

- kLa-based Scale-up: A common strategy is to maintain a constant kLa value across different scales of bioreactors [3] [4]. This ensures that cells experience the same oxygen transfer environment, supporting comparable growth and production rates. This is a process-based scale-up approach, where the critical process parameter (kLa) forms the basis for design, rather than just geometric similarity [3].

- HTC in Scale-up: Heat transfer becomes increasingly challenging at larger scales because the surface-to-volume ratio decreases. While a small lab bioreactor can easily maintain temperature, a production-scale vessel requires careful design of cooling systems to remove the substantial metabolic heat generated by a large cell mass. Validating HTC calculations ensures that temperature, a critical process parameter, can be tightly controlled at all scales.

For researchers validating transfer coefficient calculation methodologies, this comparison underscores that kLa is a well-defined, directly measurable parameter central to scale-up strategies. In contrast, HTC often requires estimation via model fitting and is critical for ensuring thermal stability, especially as reactor volume increases. A validated scale-up strategy must account for both to guarantee consistent process performance and product quality.

The Critical Role of Validation in Analytical Method Transfer and Lifecycle Management

Analytical method transfer (AMT) is a documented process that qualifies a receiving laboratory to use an analytical procedure that was originally developed and validated in a different (transferring) laboratory. The primary goal is to demonstrate that the method, when performed at the receiving site, produces results equivalent to those obtained at the originating site in terms of accuracy, precision, and reliability [7]. This process is not merely a logistical exercise but a scientific and regulatory imperative, forming a critical bridge within the broader analytical method lifecycle that spans from initial development through to routine commercial use [8].

Within pharmaceutical development, method transfer assumes particular importance for regulatory compliance and product quality assurance. Health regulators require evidence that analytical methods perform reliably across different testing sites to guarantee medicine quality and enable effective stability testing [9]. A poorly executed transfer can lead to significant issues including delayed product releases, costly retesting, regulatory non-compliance, and ultimately, compromised confidence in product quality data [7].

The Validation Imperative in Method Transfer

Establishing Equivalence Through Validation

The core principle of analytical method transfer is establishing "equivalence" or "comparability" between laboratories. This requires demonstrating that the method's key performance characteristics remain consistent across both sites. Essential parameters typically assessed during transfer include accuracy, precision, specificity, linearity, range, detection limit, quantitation limit, and robustness [7]. The validation activities must be fit-for-purpose, with the rigor commensurate to the method's complexity and criticality [8].

Validation during transfer is not a one-time event but part of a comprehensive lifecycle approach. The analytical method lifecycle encompasses method design and development, procedure qualification, and ongoing performance verification [8]. This lifecycle thinking ensures that methods remain validated not just at the point of transfer but throughout their operational use, adapting to changes in equipment, materials, or product requirements.

Regulatory Framework and Guidelines

Multiple regulatory bodies provide guidance governing analytical method transfer, including:

- USP General Chapter <1224>: Transfer of Analytical Procedures [7] [10]

- FDA Guidance for Industry: Analytical Procedures and Methods Validation (2015) [10]

- EMA Guideline: On the Transfer of Analytical Methods (2014) [10]

- ICH Q13: Addresses continuous manufacturing and material tracking models [11]

These frameworks emphasize risk-based approaches and require documented evidence that the receiving laboratory can execute the method with the same reliability as the transferring laboratory [10]. The regulatory expectation is that transfer activities are conducted according to predefined protocols with clear acceptance criteria, and thoroughly documented in formal reports [7].

Comparative Analysis of Transfer Approaches

Method Transfer Typologies

Selecting the appropriate transfer strategy depends on factors including method complexity, regulatory status, receiving laboratory experience, and risk assessment. The most common approaches are compared in the table below.

Table 1: Analytical Method Transfer Approaches Comparison

| Transfer Approach | Description | Best Suited For | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative Testing [7] [10] | Both laboratories analyze identical samples; results statistically compared | Established, validated methods; similar lab capabilities | Requires robust statistical analysis, sample homogeneity, detailed protocol |

| Co-validation [7] [10] [8] | Method validated simultaneously by both laboratories | New methods; methods developed for multi-site use | High collaboration, harmonized protocols, shared responsibilities |

| Revalidation [7] [10] | Receiving laboratory performs full/partial revalidation | Significant differences in lab conditions/equipment; substantial method changes | Most rigorous, resource-intensive; full validation protocol needed |

| Transfer Waiver [7] | Transfer process formally waived based on strong justification | Highly experienced receiving lab; identical conditions; simple, robust methods | Rare, high regulatory scrutiny; requires strong scientific and risk justification |

| Data Review [10] | Receiving lab reviews historical validation data without experimentation | Simple compendial methods with minimal risk | Limited to low-risk scenarios with substantial existing data |

Quantitative Impact of Transfer Methodologies

The choice of transfer methodology has significant operational and financial implications. Recent industry data quantifies these impacts, particularly when transfers encounter problems.

Table 2: Economic Impact of Method Transfer Efficiency

| Performance Metric | Traditional/Manual Transfer | Digital/Standardized Transfer | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deviation Investigation Costs | $10,000 - $14,000 average; up to $50,000 - $1M for product impact [12] | Significant reduction through error prevention | Industry analysis |

| Daily Delay Cost for Commercial Therapy | ≈$500,000 unrealized sales average; $5M-$30M for blockbuster drugs [12] | Days shaved from critical path through efficient transfer | Market analysis |

| Method Exchange Time | Days to weeks due to manual transcription and reconciliation | Hours to days with machine-readable, vendor-neutral exchange [12] | Pilot study data |

| Error Rate in Method Recreation | High due to manual transcription and parameter reconciliation | Minimal with standardized digital templates [12] | Industry observation |

Experimental Protocols for Transfer Validation

Core Experimental Workflow

A structured approach is essential for successful method transfer validation. The following diagram outlines the critical phases and decision points in a comprehensive transfer protocol.

Diagram 1: Method Transfer Validation Workflow

Key Experimental Methodologies

Comparative Testing Protocol

For comparative testing approaches, both laboratories analyze the same set of samples—typically including reference standards, spiked samples, and production batches [7]. The experimental sequence should include:

Sample Selection and Preparation: Homogeneous, representative samples are characterized and distributed to both laboratories with proper handling and shipment controls to maintain stability [7] [10].

Parallel Testing: Both laboratories perform the analytical method according to the approved protocol, with meticulous documentation of all raw data, instrument printouts, and calculations [7].

Statistical Analysis: Results are compared using appropriate statistical methods as outlined in the protocol, which may include t-tests, F-tests, equivalence testing, or ANOVA [7] [10]. The specific statistical approach should be predetermined with clearly defined acceptance criteria.

Risk-Based Spiking Studies

Spiking studies demonstrate method accuracy for impurity tests, such as size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) for aggregates and low-molecular-weight species. A case study illustrates a fit-for-purpose approach:

- Spike Material Generation: Stable aggregates created through controlled oxidation reactions; LMW species generated via reduction reactions [8].

- Linearity and Recovery Assessment: Good linearity between expected aggregates spike and actual UV response (correlation coefficient ≈1), with 90-100% recovery for aggregates and 80-100% recovery for LMW species [8].

- Comparative Method Evaluation: Two SEC methods showed different sensitivity to spiked samples despite both passing dilution linearity, highlighting the importance of spiking studies for method selection [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful method transfer requires carefully selected materials and reagents. The following table details key solutions and their functions in transfer experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Method Transfer

| Reagent/Material | Function in Transfer | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards [7] [10] | System suitability testing; quantification reference | Traceability to primary standards; proper qualification and storage |

| Spiked Samples [8] | Accuracy and recovery assessment | Representative impurity generation; stability documentation |

| Chromatography Columns [10] [12] | Separation performance | Column chemistry equivalence; lot-to-lot variability assessment |

| Mobile Phase Reagents [7] [10] | Liquid chromatography eluent preparation | Grade equivalence; preparation procedure standardization |

| System Suitability Solutions [10] | Verify system performance before sample analysis | Defined acceptance criteria for critical parameters (e.g., retention time, peak symmetry) |

Digital Transformation in Method Transfer

The Digital Method Exchange Paradigm

Traditional method transfer dominated by document-based exchanges (PDFs) creates significant inefficiencies. Manual transcription into different chromatography data systems (CDS) drives rework, deviations, and delays, especially when engaging contract partners [12]. Digital transformation addresses these challenges through:

- Machine-Readable Methods: Vendor-neutral, standardized method exchange using formats like Allotrope Data Format (ADF) [12].

- Structured Data Repositories: FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) repositories for method version control and exchange [12].

- Reduced Manual Effort: Elimination of transcription errors and reconciliation activities [12].

Experimental evidence from a Pistoia Alliance pilot demonstrated successful two-way exchange of standardized HPLC-UV methods between different CDSs and pharmaceutical company sites using ADF-based method objects, reporting reduced manual effort and improved reproducibility [12].

Integration with Lifecycle Management

Digital method exchange aligns with emerging regulatory guidance, including ICH Q14 on analytical procedure development and Q2(R2) on validation, both emphasizing lifecycle management and data integrity [12]. The digital approach creates a foundation for continuous method verification, a key trend in pharmaceutical validation for 2025 [13].

The following diagram illustrates how digital transformation enables seamless method transfer within a comprehensive lifecycle management framework.

Diagram 2: Digital Method Transfer Lifecycle

Validation plays a critical role in ensuring the success of analytical method transfer and ongoing lifecycle management. A risk-based approach to transfer strategy selection, combined with structured experimental protocols and comprehensive documentation, provides the foundation for regulatory compliance and data integrity. The emergence of digital transformation in method exchange addresses longstanding industry inefficiencies, reducing errors and accelerating transfer cycles.

As the pharmaceutical industry evolves toward continuous manufacturing [11] and increasingly complex analytical techniques, the principles of robust method transfer validation become even more essential. By implementing the comparative approaches, experimental methodologies, and digital tools outlined in this guide, researchers and drug development professionals can ensure the reliability of analytical data across multiple sites, ultimately protecting product quality and patient safety.

This guide objectively compares the regulatory approaches of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP), and the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) in the context of analytical method validation, providing a framework for validating transfer coefficient calculation methodologies.

Executive Comparison: FDA, USP, and ICH at a Glance

The table below summarizes the core philosophies and attributes of each regulatory framework.

| Feature | ICH | USP | FDA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Philosophy | Risk-based, product lifecycle-oriented [14] [15] | Prescriptive, procedure-focused [15] | Adopts ICH guidelines; emphasizes risk and lifecycle management [14] [16] |

| Primary Scope | Global harmonization for drug development and manufacturing [14] | U.S. centric, with international influence; specific monographs and general chapters [15] | U.S. regulatory requirements for drug approval and quality [14] |

| Key Documents | Q2(R2) Validation, Q14 Development, Q8/Q9/Q10 Quality Systems [14] [17] | General Chapters <1225> Validation, <1220> Analytical Lifecycle [15] [18] | Adopts ICH Q2(R2) and Q14; issues specific guidance on topics like nitrosamine impurities [14] [19] |

| Approach to Change Management | Flexible, science- and risk-based, allowing for post-approval changes within a quality system [14] [15] | More rigid, often requiring compliance with specific, updated monograph procedures [15] | Supports a science-based approach for post-approval changes, aligned with ICH Q12 [14] |

Detailed Analysis of Validation Parameters and Requirements

A deeper comparison of technical validation requirements reveals how the philosophical differences manifest in practice.

| Validation Parameter | ICH Approach | USP Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Specificity | Emphasizes demonstration of non-interference in the presence of expected components [15] | Often requires specific tests, such as chromatographic resolution tests [15] |

| Method Robustness | Integrated throughout method development and validation; a formalized part of the lifecycle [14] [15] | Typically treated as a discrete validation element [15] |

| Precision | Differentiates between repeatability, intermediate precision, and reproducibility [14] [15] | Focuses primarily on repeatability and reproducibility [15] |

| Linearity/Response Function | "Linearity" replaced by "Response (Calibration Model)"; explicitly includes nonlinear and multivariate models [18] | Traditionally focuses on a linear response function, which can cause confusion with nonlinear techniques [18] |

| Setting Acceptance Criteria | Employs tolerance intervals and confidence intervals based on method capability; allows for risk-based justification [15] | Often specifies fixed numerical values in monographs or follows prescriptive statistical methods [15] |

| Documentation | Flexible and proportional to the risk level of the method and the change being made [15] | Requires more standardized templates and documentation, often regardless of risk level [15] |

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

For researchers designing validation studies, the following core protocols, aligned with ICH Q2(R2) and USP, are essential.

Protocol for Accuracy Assessment

- Objective: To demonstrate the closeness of agreement between the test result and a true reference value [14].

- Methodology: Prepare a placebo sample and spike it with a known concentration of the analyte (e.g., 50%, 100%, 150% of the target concentration). Analyze a minimum of n=9 determinations across a minimum of three concentration levels. The sample matrix should be representative, and sample processing must mimic routine conditions [14] [18].

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percent recovery of the known analyte or the difference between the mean and the accepted true value. Compare results against pre-defined acceptance criteria, which are often derived from the product's specification range [14].

Protocol for Precision Evaluation

- Objective: To measure the degree of scatter among a series of measurements obtained from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample [14].

- Methodology:

- Repeatability (Intra-assay): Analyze a minimum of n=6 determinations at 100% of the test concentration under identical conditions (same analyst, same day, same equipment) [14].

- Intermediate Precision: Demonstrate the reliability of results under normal laboratory variations (e.g., different days, different analysts, different equipment). The experimental design should include a minimum of two variables [14].

- Data Analysis: Calculate the relative standard deviation (RSD) for the results. The aim is to understand the factors contributing to total variance to determine an appropriate replication strategy for routine analysis [14] [18].

Protocol for Specificity/Selectivity

- Objective: To unequivocally assess the analyte in the presence of other components like impurities, degradants, or matrix [14].

- Methodology: For chromatographic assays, inject individually solutions of the analyte, placebo, potential impurities, and degradation products. For a stability-indicating method, forced degradation studies (e.g., exposure to heat, light, acid, base, oxidation) are performed on the drug substance or product [14].

- Data Analysis: Assess that the analyte peak is pure and unaffected by other peaks. Resolution factors between the analyte and the closest eluting potential interferent are calculated and must meet pre-set criteria [14] [15].

Workflow Diagram: Analytical Procedure Lifecycle

The following diagram illustrates the modern, holistic lifecycle of an analytical procedure as championed by ICH Q2(R2)/Q14 and USP <1220>, which represents a shift from a one-time validation event to continuous verification [14] [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials and concepts critical for conducting robust analytical method validation studies.

| Item / Concept | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Analytical Target Profile (ATP) | A prospective summary defining the intended purpose of an analytical procedure and its required performance characteristics. It is the foundational concept for a lifecycle approach, guiding development, validation, and continuous monitoring [14] [18]. |

| Quality Risk Management (ICH Q9) | A systematic process for the assessment, control, communication, and review of risks to product quality. It is used to prioritize validation efforts based on potential impact [14] [17]. |

| Reference Standards | Highly characterized substances used to calibrate equipment or validate analytical methods. USP provides compendial standards, and other qualified sources are used for non-compendial methods. |

| System Suitability Samples | A defined mixture of analytes used to verify that the chromatographic or spectroscopic system is performing adequately at the time of the test, as required by USP and ICH guidelines. |

| Forced Degradation Samples | Samples of the drug substance or product that have been intentionally stressed under various conditions (heat, light, acid, base, oxidation) to generate degradants. These are essential for demonstrating the specificity of a stability-indicating method [14]. |

Strategic Considerations for Implementation

Choosing the correct guideline depends on your product's target market and the regulatory strategy. For global submissions, adhering to ICH Q2(R2) and Q14 provides a strong, harmonized foundation that is accepted by the FDA and other major regulatory bodies [14] [16]. For the U.S. market, USP standards are legally recognized and must be followed for compendial methods, often requiring a hybrid approach that satisfies both ICH's scientific principles and USP's specific monograph requirements [15]. The FDA expects compliance with ICH guidelines for NDAs and ANDAs, and its inspectors will assess the entire quality system, including method lifecycle management, during inspections [14].

In the rigorous world of scientific research and drug development, the reliability of analytical methods forms the bedrock of trustworthy data. The process of validating transfer coefficient calculation methodologies, along with other critical analytical procedures, is fraught with interconnected challenges that can compromise data integrity and decision-making. Among the most pervasive hurdles are data scarcity, model generalizability, and cross-laboratory variability. Data scarcity limits the robustness of models, poor generalizability restricts their practical application, and cross-laboratory variability introduces inconsistencies that can invalidate otherwise sound methods. These challenges are particularly acute in fields like pharmaceutical development and thermal engineering, where predictive models and standardized assays are essential. This guide objectively compares the performance of various methodological approaches designed to overcome these challenges, providing a structured comparison of their efficacy based on experimental data and established protocols.

Comparative Analysis of Methodological Approaches

The table below synthesizes experimental data and performance outcomes from various studies that tackled these core challenges, offering a direct comparison of different strategies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Methodologies Addressing Data Scarcity and Generalizability

| Methodology / Approach | Reported Performance Metrics | Key Challenges Addressed | Domain / Application | Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wide Neural Network (WNN) [20] | RMSE: 1.97, R²: 0.91, Prediction Error: <5% | Model Generalizability | HTC Prediction for Refrigerants | Outperformed Linear Regression and Support Vector Machines on a dataset of 22,608 points across 18 refrigerants [20]. |

| Fine-Tuned Convolutional Neural Network [21] | Successful prediction of time-to-failure and shear stress on unseen data | Data Scarcity, Cross-Laboratory Variability | Laboratory Earthquake Prediction | A model pre-trained on one lab configuration (DDS) was successfully fine-tuned with limited data (~3% of layers) to predict events in a different configuration (Biaxial) [21]. |

| Domain Adaptation via Data Augmentation [22] | Improved prediction accuracy and reliability on secondary device | Cross-Laboratory Variability, Model Generalizability | Blood-Based Infrared Spectroscopy | A data augmentation technique that incorporated device-specific differences enhanced model transferability between two FTIR devices [22]. |

| Benchmarking Framework for Cross-Dataset Generalization [23] | Revealed substantial performance drops on unseen datasets; identified best source dataset (CTRPv2) | Model Generalizability, Data Scarcity | Drug Response Prediction (DRP) | Systematic evaluation of 6 models showed no single model performed best, underscoring the need for rigorous generalization assessments [23]. |

| Generic Validation [8] | Reduced validation burden for new products; speed up of IND submissions | Cross-Laboratory Variability, Data Scarcity | QC Method Validation for Biologics | A platform assay validated with representative material was applied to similar products (e.g., monoclonal antibodies) without product-specific validation [8]. |

| Covalidation [8] | Method validated for multiple sites simultaneously | Cross-Laboratory Variability | Analytical Method Transfer | Intermediate precision and other studies were performed at a receiving site during initial validation, combining data into a single package for multiple sites [8]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Workflows

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear roadmap for implementation, this section details the methodologies behind the compared approaches.

Protocol: Cross-Dataset Generalization Analysis for Drug Response Prediction

This protocol, derived from a community benchmarking effort, provides a standardized workflow for assessing model generalizability, a critical step in validating computational methodologies [23].

- Benchmark Dataset Construction: Compile a dataset integrating multiple independent sources. The cited study used five public drug screening datasets (CCLE, CTRPv2, gCSI, GDSCv1, GDSCv2), including drug response data (e.g., Area Under the Curve - AUC), multiomics data for cell lines (e.g., gene expression, mutations), and drug representation data (e.g., fingerprints, descriptors) [23].

- Data Preprocessing and Splitting: Ensure data quality by applying consistent filtering (e.g., R² > 0.3 for dose-response curves). Precompute training, validation, and test splits to guarantee consistent evaluation across all models [23].

- Model Training and Standardization: Select a set of representative models (e.g., five DL-based models and one ML model like LightGBM). Adjust all model codes to conform to a unified, modular structure to ensure consistent execution [23].

- Cross-Dataset Evaluation: Train models on data from one or more "source" datasets. Evaluate the trained models on hold-out test sets from "target" datasets that were not used during training.

- Performance Assessment: Calculate a set of evaluation metrics that quantify both absolute performance (e.g., predictive accuracy like RMSE, R²) and relative performance (e.g., the performance drop compared to within-dataset results) [23].

Protocol: Domain Adaptation for Cross-Device Spectroscopy

This protocol outlines a practical approach to mitigate cross-laboratory variability using data augmentation, as demonstrated in FTIR spectroscopy [22].

- Sample Collection and Calibration: Collect a primary dataset using multiple devices or at multiple sites. For calibration, obtain a smaller subset of samples measured on all devices.

- Data Preprocessing: Apply a standardized preprocessing protocol to all spectral data. This typically includes:

- Truncating non-informative spectral regions.

- Applying normalization (e.g., L2 normalization) to standardize spectra.

- Excluding regions devoid of relevant peaks [22].

- Domain Adaptation via Augmentation: Use the calibration set to characterize the spectral differences between devices. Synthetically expand the training data by incorporating these device-specific spectral nuances, creating an augmented dataset that reflects the variability across all target devices [22].

- Model Training and Validation: Train the machine learning model on the augmented dataset. Validate the model's performance on a hold-out test set measured exclusively on the secondary device(s) to confirm improved accuracy and reliability [22].

Workflow: Analytical Method Lifecycle and Transfer

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for managing an analytical method from design through transfer, highlighting stages that address these key challenges.

Analytical Method Lifecycle Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of robust methodologies relies on a set of key materials and conceptual tools.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Method Validation and Transfer

| Item / Solution | Function / Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Representative Spiking Material | Used in accuracy/recovery studies (e.g., SEC validation) to simulate impurities like aggregates and LMW species when naturally occurring materials are scarce [8]. | Quality Control Method Validation |

| Platform Assays | Pre-validated, non-product-specific methods (e.g., for monoclonal antibodies) that enable generic validation, reducing data needs for new products [8]. | Biologics Development |

| Calibration/QC Set | A small set of samples measured across all devices/labs to quantify systematic differences and enable domain adaptation [22]. | Cross-Device/Laboratory Studies |

| Standardized Benchmark Dataset | A fixed set of data from multiple sources with pre-computed splits, enabling fair comparison of model generalizability [23]. | Computational Model Development |

| Reference Standards | Separately weighed stock solutions used to demonstrate accuracy of standard preparation; must compare within a tight margin (e.g., 5%) [24]. | Dose Formulation Analysis |

| System Suitability Test (SST) | A check performed to ensure the analytical system (e.g., HPLC) is operating with sufficient sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility at the time of analysis [24]. | Chromatographic Methods |

The comparative data and detailed protocols presented in this guide demonstrate that while data scarcity, model generalizability, and cross-laboratory variability remain significant challenges, proven methodological frameworks exist to manage them. No single solution is universally superior; the choice depends on the specific context, be it computational model benchmarking or physical analytical method transfer. The consistent theme across successful approaches is a proactive, lifecycle-oriented strategy that prioritizes robustness from initial method design through final deployment and monitoring. By adopting these comparative insights and structured experimental workflows, researchers and drug development professionals can significantly enhance the reliability and credibility of their analytical results.

From Theory to Practice: Computational, Statistical, and Machine Learning Approaches

In the field of drug development, particularly during bioprocess scale-up, the accurate prediction of mass transfer coefficients is a critical challenge. Traditional empirical correlations have long been the foundational toolkit for researchers and scientists tasked with designing and scaling bioreactor systems. These correlations, often derived from experimental data, provide a mathematical framework for predicting system behavior without requiring a complete theoretical understanding of all underlying physical phenomena [25].

This guide provides an objective comparison of these traditional methodologies, focusing on their performance in predicting the volumetric mass-transfer coefficient (kLa)—a parameter paramount to ensuring adequate oxygen supply in cell cultures and fermentations. The content is framed within the broader thesis of validating transfer coefficient calculation methodologies, presenting experimental data and protocols to equip professionals with the information needed to critically evaluate these established tools.

Principles of Traditional Empirical Correlations

Empirical research is defined as any study whose conclusions are exclusively derived from concrete, verifiable evidence, relying on direct observation and experimentation to measure reality [26] [27]. In the context of bioprocess engineering, traditional empirical correlations for mass transfer are quintessential examples of this approach. They are formulated by observing system outputs under controlled inputs and fitting mathematical expressions to the resultant data.

The fundamental principle underpinning these correlations is dimensional analysis, which relates the target variable (typically kLa) to key, easily measurable operating and geometric parameters. The most common form, van’t Riet’s correlation, exemplifies this principle [25]:

kLa = K (P/V)^α (V_S)^β

This equation demonstrates the core assumption that the volumetric mass-transfer coefficient can be predicted primarily from the volumetric power input (P/V), a measure of energy dissipation, and the superficial gas velocity (V_S), which characterizes the gas flow rate. The constant K and the exponents α and β are empirically determined and are sensitive to the physical properties of the system and the fluid.

Comparative Analysis of Key Empirical Correlations

The table below summarizes the most common types of empirical correlations used for predicting kLa in stirred-tank bioreactors, along with their inherent advantages and drawbacks [25].

Table 1: Comparison of Empirical Correlation Types for kLa Prediction

| Correlation Basis | Typical Correlation Form | Key Parameters | Primary Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Input | ( kL a = K (Pg/V)^\alpha V_S^\beta ) | Pg/V (Gassed power/volume), VS (Superficial gas velocity) | Simple form; widely recognized and frequently used. | Poor accuracy with complex broths; sensitive to system coalescence properties. |

| Dimensionless Numbers | ( Sh = f(Re, Fr, Sc) ) | Reynolds No. (Re), Froude No. (Fr), Schmidt No. (Sc) | Theoretically more generalizable across different scales. | Complex form; requires knowledge of multiple fluid properties. |

| Relative Gas Dispersion | ( kL a = f(N/N{cd}) ) | N (Impeller speed), Ncd (Critical impeller speed for gas dispersion) | Directly links to a key physical phenomenon (gas dispersion). | Difficult to determine Ncd accurately across scales. |

The performance of these correlations is highly variable. A study by Pappenreiter et al., conducted in a 15-L bioreactor, demonstrated that the presence of culture medium and additives can triple the kLa value compared to a simple water-antifoam system, underscoring a significant limitation of correlations derived from model systems [25]. The following workflow outlines the typical process for developing and validating such a correlation.

Figure 1: Empirical Correlation Development Workflow

Experimental Protocols for kLa Determination

The validation of any empirical correlation relies on robust experimental data. The following section details standard protocols for measuring the volumetric mass-transfer coefficient, which serves as the benchmark for evaluating correlation performance.

Standard Dynamic Gassing-Out Method

This is the most commonly used technique for determining kLa in bioreactors.

Objective: To experimentally measure the volumetric oxygen mass-transfer coefficient (kLa) in a stirred-tank bioreactor.

Principle: The method involves monitoring the increase in dissolved oxygen (DO) concentration after a step change in the oxygen concentration in the gas phase (e.g., from nitrogen to air).

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Key Materials

| Item Name | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Bioreactor System | A vessel with controlled stirring, temperature, gas sparging, and data acquisition. |

| Polarographic DO Probe | The sensor that measures the dissolved oxygen concentration in the broth. |

| Data Acquisition System | Records the DO probe's output over time for subsequent analysis. |

| Nitrogen Gas (N₂) | Used to deoxygenate the liquid medium at the start of the experiment. |

| Air or Oxygen Gas (O₂) | Used to create the step increase in oxygen concentration for the measurement. |

| Sodium Sulfite (Na₂SO₃) | Used in the chemical method for kLa determination to chemically consume oxygen. |

| Cobalt Chloride (CoCl₂) | Serves as a catalyst for the oxidation of sodium sulfite. |

Procedure:

- System Preparation: Fill the bioreactor with a known volume of the liquid medium (e.g., water or culture broth). Set and stabilize the temperature, stirrer speed (N), and aeration rate (Q).

- Deoxygenation: Sparge the vessel with nitrogen gas until the dissolved oxygen concentration drops to a steady, near-zero level.

- Re-aeration: Quickly switch the gas flow from nitrogen to air (or oxygen). Ensure the gas flow rate, pressure, and stirrer speed remain constant.

- Data Collection: Record the dissolved oxygen concentration as a function of time until it reaches a new steady-state value (C*).

- Data Analysis: The kLa is determined from the slope (m) of the linear regression of ln((C* - C)/C*) versus time (t), where kLa = -m.

Data Analysis and kLa Calculation

The data collected from the dynamic method is analyzed based on the oxygen balance in the system. The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the measured data, the model, and the final kLa result.

Figure 2: kLa Calculation from Experimental Data

Limitations and Critical Pitfalls

While indispensable, traditional empirical correlations possess significant limitations that researchers must acknowledge to avoid misapplication.

Sensitivity to Fluid Properties: Correlations developed in water or simple solutions show poor accuracy in cell culture broths. The presence of salts, sugars, surfactants, and cells themselves drastically alters bubble coalescence behavior, interfacial area, and thus, the kLa value [25]. A correlation's constant

Kis highly sensitive to these coalescing properties.Limited Scalability: Most correlations are developed in small-scale bioreactors characterized by homogeneous, high-turbulence environments. In large-scale vessels, turbulence is heterogeneous, being intense near the impeller and much weaker in the bulk. This leads to systematic over-prediction of kLa when laboratory-scale correlations are applied to commercial-scale systems [25].

Dependence on Equipment Geometry: The exponents in power-input-based correlations can be dependent on bioreactor and impeller geometry (e.g., impeller type, baffle design). A correlation derived for one specific geometric configuration may not be valid for another, limiting its general applicability.

Statistical versus Practical Significance: When comparing correlations or model outputs, relying solely on correlation coefficients (e.g., Pearson's r) is inadequate. These coefficients measure the strength of a linear relationship but not necessarily agreement or accuracy. They are also sensitive to the range of observations, making comparisons across different studies problematic [28] [29]. A strong correlation does not guarantee a good prediction.

Application Scopes and Best Practices

The effective use of traditional empirical correlations is bounded by their specific application scopes. The choice of correlation should be guided by the specific stage of process development and the available system knowledge.

Table 3: Guideline for Correlation Application Scope

| Development Stage | Recommended Correlation Type | Rationale & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Early Screening / Feasibility | Simple Power Input & Gas Velocity | Provides quick, order-of-magnitude estimates with minimal data. Useful for initial bioreactor selection. |

| Laboratory-Scale Process Optimization | Dimensionless Number-based or system-specific | Offers better interpolation within the design space of a specific, well-characterized small-scale system. |

| Pilot-Scale Translation | Site-Specific Correlation (Highly Recommended) | A correlation should be developed from data collected at the pilot scale to account for changing hydrodynamics. |

| Commercial-Scale Design | Not Recommended to scale-up directly from lab-scale correlations. | Scale-up requires a combination of pilot-scale data, fundamental principles, and computational fluid dynamics (CFD). |

Best Practices for Application:

- Define the Scope Clearly: Use a correlation only within the range of parameters (P/V, V_S, fluid properties) for which it was developed.

- Develop Site-Specific Models: The most reliable approach is to create a bespoke correlation for your specific bioreactor, impeller geometry, and culture broth.

- Prioritize Effect Size over P-values: When building or comparing models, focus on the estimated effect sizes and their confidence intervals (e.g., the values of α and β) rather than just statistical significance [30]. This provides a more realistic understanding of the correlation's predictive power.

- Validate with Independent Data: Always test the performance of any correlation against a set of experimental data that was not used in its creation.

Leveraging Total Error and Accuracy Profiles for Analytical Method Transfer

In the dynamic landscape of pharmaceutical development, the transfer of analytical methods between laboratories is a critical process that ensures consistency and reliability of data across different sites. Within the broader context of validating transfer coefficient calculation methodologies, the concept of total error has emerged as a scientifically rigorous framework for demonstrating method comparability. Unlike traditional approaches that treat accuracy and precision separately, the total error paradigm combines both random (precision) and systematic (bias) errors into a single, comprehensive measure that more accurately reflects the method's performance under real-world conditions.

Analytical method transfer is a documented process that qualifies a receiving laboratory to use an analytical method that originated in a transferring laboratory, with the primary goal of demonstrating that both laboratories can perform the method with equivalent accuracy, precision, and reliability [7]. This process is particularly crucial in scenarios involving multi-site operations, contract research/manufacturing organizations (CROs/CMOs), technology changes, or method optimization initiatives [7]. The fundamental principle is to establish equivalence or comparability between the two laboratories' abilities to execute the method while maintaining consistent performance characteristics.

The total error approach provides significant advantages during method transfer by requiring a single criterion based on an allowable out-of-specification (OOS) rate at the receiving lab, thereby overcoming the difficulty of allocating separate acceptance criteria between precision and bias [31]. This integrated perspective offers a more realistic assessment of method performance and facilitates better decision-making during transfer activities, ultimately strengthening the validation of transfer coefficient calculation methodologies that form the core of this research thesis.

Comparative Analysis of Method Transfer Approaches

The selection of an appropriate transfer strategy depends on multiple factors, including the method's complexity, regulatory status, receiving laboratory experience, and risk considerations. Regulatory bodies such as the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) provide guidance on these approaches in general chapter <1224> "Transfer of Analytical Procedures" [7]. The four primary methodologies include comparative testing, co-validation, revalidation, and transfer waivers, each with distinct characteristics and implementation requirements.

Structured Comparison of Transfer Approaches

The table below provides a comprehensive comparison of the four primary methodological approaches for analytical method transfer:

Table 1: Comparison of Analytical Method Transfer Approaches

| Transfer Approach | Description | Best Suited For | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative Testing [7] [32] | Both laboratories analyze identical samples; results are statistically compared to demonstrate equivalence | Established, validated methods; laboratories with similar capabilities and equipment | Requires robust statistical analysis, homogeneous samples, and detailed protocol; most common approach |

| Co-validation [7] [32] | Method is validated simultaneously by both transferring and receiving laboratories | New methods or methods developed specifically for multi-site implementation | Requires high collaboration, harmonized protocols, and shared validation responsibilities |

| Revalidation [7] [32] | Receiving laboratory performs full or partial revalidation of the method | Significant differences in laboratory conditions/equipment; substantial method changes | Most rigorous and resource-intensive approach; requires complete validation protocol and report |

| Transfer Waiver [7] [32] | Formal transfer process is waived based on scientific justification and data | Highly experienced receiving laboratory; identical conditions; simple, robust methods; pharmacopoeial methods | Rarely used with high regulatory scrutiny; requires robust documentation and risk assessment |

Total Error Versus Traditional Approaches

Traditional method comparison approaches, as outlined in USP <1010>, utilize separate tests for accuracy and precision, which presents challenges due to the interdependence of these parameters [31]. In contrast, the total error approach combines both systematic bias (accuracy) and random variation (precision) into a single criterion that corresponds to an allowable out-of-specification rate [31]. This methodology provides a more holistic view of method performance and facilitates the setting of statistically sound acceptance criteria that reflect the real-world analytical process.

The total error approach is particularly valuable in method transfer and bridging studies because it directly addresses the probability of obtaining correct results, which aligns with the fundamental purpose of analytical procedures in quality control. By employing this methodology, researchers can establish acceptance criteria that ensure analytical procedures will produce reliable results within specified tolerance limits when transferred between laboratories [31].

Experimental Protocols for Method Transfer

Total Error Methodology Implementation

The implementation of total error principles in analytical method transfer requires careful experimental design and execution. The following workflow outlines the key stages in this process:

Diagram 1: Total Error Method Transfer Workflow

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Comparative Testing

The following protocol outlines the specific steps for implementing a total error approach in comparative testing, the most common method transfer approach:

Phase 1: Pre-Transfer Planning and Protocol Development

- Define Acceptance Criteria: Establish total allowable error (TEa) criteria based on product specifications and the analytical procedure's purpose [33] [31]. These criteria should reflect the maximum acceptable error that still ensures method suitability for its intended use.

- Form Cross-Functional Teams: Designate leads and team members from both transferring and receiving laboratories, including representatives from Analytical Development, QA/QC, and Operations [7].

- Conduct Gap Analysis: Compare equipment, reagents, software, environmental conditions, and personnel expertise between the two laboratories to identify potential discrepancies that could impact method performance [7] [32].

- Develop Detailed Transfer Protocol: Create a comprehensive protocol specifying method details, responsibilities, materials, experimental design, acceptance criteria, and statistical analysis plan [7]. The protocol should explicitly define how total error will be calculated and evaluated.

Phase 2: Execution and Data Generation

- Personnel Training: Ensure receiving laboratory analysts are thoroughly trained by transferring laboratory personnel, with particular emphasis on critical method parameters and potential pitfalls [7] [32].

- Equipment Qualification: Verify that all necessary equipment at the receiving laboratory is properly qualified, calibrated, and comparable to equipment at the transferring laboratory [7].

- Sample Preparation and Analysis: Prepare homogeneous, representative samples (e.g., spiked samples, production batches, placebo) for analysis by both laboratories [7]. The number of samples and replicates should provide sufficient statistical power for total error estimation.

- Data Collection: Meticulously record all raw data, instrument printouts, calculations, and any deviations from the protocol [7].

Phase 3: Data Evaluation and Reporting

- Statistical Analysis: Perform statistical comparison using a total error approach that combines estimates of bias (systematic error) and precision (random error) from both laboratories [31]. The following calculations are essential:

- Bias Calculation: Determine the mean difference between results obtained at the receiving and transferring laboratories.

- Precision Estimation: Calculate the standard deviation or relative standard deviation of results at each laboratory.

- Total Error Calculation: Combine bias and precision estimates to determine the probability of future results falling within acceptance limits.

- Evaluation Against Acceptance Criteria: Compare the calculated total error and its confidence intervals against the pre-defined TEa criteria [31].

- Deviation Investigation: Thoroughly investigate and document any deviations from the protocol or out-of-specification results [7].

- Transfer Report Preparation: Prepare a comprehensive report summarizing transfer activities, results, statistical analysis, and conclusions regarding the success of the transfer [7] [32].

Experimental Design Considerations

When designing experiments for method transfer using total error principles, several statistical considerations are critical:

- Sample Size: Ensure sufficient sample size to provide adequate statistical power for detecting meaningful differences between laboratories. Practical sample sizes should balance statistical rigor with operational feasibility [31].

- Experimental Designs: Various experimental designs can be employed in method transfer studies, including completely randomized designs, balanced designs accounting for multiple factors, and designs that incorporate time as a variable to assess intermediate precision [31].

- Data Analysis Methods: The total error approach can be implemented using statistical methods such as tolerance intervals, uncertainty profiles, or accuracy profiles that graphically represent the relationship between the measured value and the total error across the method's range [31].

Performance Metrics and Acceptance Criteria

Establishing Scientifically Sound Acceptance Limits

The establishment of appropriate acceptance criteria is fundamental to successful method transfer. These criteria should be based on method performance characteristics, product specifications, and the analytical procedure's intended purpose [32]. The total error approach facilitates this process by providing a single, comprehensive criterion that corresponds to an acceptable out-of-specification rate [31].

Table 2: Typical Acceptance Criteria for Analytical Method Transfer

| Test | Typical Criteria | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Identification [32] | Positive (or negative) identification obtained at the receiving site | Qualitative assessment; no quantitative criteria |

| Assay [32] | Absolute difference between the sites: 2-3% | Criteria may vary based on product specifications and method capability |

| Related Substances [32] | Requirements vary depending on impurity levels:• More generous criteria for low levels (<0.5%)• Recovery of 80-120% for spiked impurities | For low-level impurities, criteria may be based on absolute difference rather than percentage |

| Dissolution [32] | Absolute difference in mean results:• NMT 10% when <85% dissolved• NMT 5% when >85% dissolved | Different criteria apply based on dissolution stage |

Total Allowable Error Values

Total allowable error (TEa) values provide essential reference points for setting acceptance criteria during method transfer. These values may be derived from various sources, including regulatory requirements, pharmacopeial standards, and method validation data [33]. The table below illustrates representative TEa values for selected analytes:

Table 3: Representative Total Allowable Error (TEa) Values

| Analyte | Fluid | Total Allowable Error | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT) | Serum | ±15% or 6 U/L (greater) | CLIA, CAP [33] |

| Albumin | Serum | ±8% | CLIA, CAP [33] |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) | Serum | ±20% | CLIA, CAP [33] |

| Amylase | Serum | ±20% | CLIA, CAP [33] |

| Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST) | Serum | ±15% or 6 U/L (greater) | CLIA, CAP [33] |

| Bilirubin, Total | Serum | ±20% or 0.4 mg/dL (greater) | CLIA, CAP [33] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of total error principles in analytical method transfer requires specific materials and reagents that ensure consistency and comparability between laboratories. The following table details essential components of the method transfer toolkit:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Method Transfer

| Item | Function | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards [7] | Qualified reference materials used to establish method accuracy and calibration | Must be traceable, properly qualified, and of appropriate purity; stability should be verified |

| System Suitability Test Materials | Samples used to verify that the analytical system is operating correctly before analysis | Should be stable, representative of actual samples, and sensitive to critical method parameters |

| Spiked Samples [32] | Samples with known amounts of analyte added, used to determine accuracy and recovery | Must be prepared using appropriate solvents and techniques to ensure accurate concentration |

| Placebo/Blank Samples | Matrix without active ingredient, used to assess specificity and interference | Should represent the complete formulation without the active pharmaceutical ingredient |

| Stability Solutions | Solutions used to evaluate sample stability under various conditions | Must cover relevant storage conditions and timepoints encountered during analysis |

| Critical Reagents [7] | Method-specific reagents essential for proper method performance (e.g., buffers, derivatizing agents) | Should be sourced from qualified suppliers with consistent quality; preparation procedures must be standardized |

The application of total error and accuracy profiles in analytical method transfer represents a significant advancement over traditional approaches that treat bias and precision separately. This integrated methodology provides a more scientifically rigorous framework for demonstrating comparability between laboratories, thereby supporting the broader validation of transfer coefficient calculation methodologies. By implementing the protocols, acceptance criteria, and experimental designs outlined in this guide, researchers and drug development professionals can enhance the reliability and regulatory compliance of their method transfer activities, ultimately ensuring consistent product quality across multiple manufacturing and testing sites.

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) for Predicting Localized Transfer Coefficients

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) has become an indispensable tool for predicting localized heat transfer coefficients (HTCs), parameters crucial to the design of thermal management systems across industries from electronics to manufacturing. The accuracy of these predictions, however, is fundamentally dependent on the rigorous validation of CFD methodologies against controlled experimental data. This guide objectively compares the performance of different CFD validation approaches by examining their application in contemporary research, providing a framework for selecting appropriate methodologies based on application requirements and available experimental resources. The following analysis is framed within the broader context of thesis research focused on validating transfer coefficient calculation methodologies, with particular emphasis on protocol details, quantitative performance metrics, and the essential toolkit required for implementation.

Comparative Analysis of CFD Validation Methodologies

Table 1: Comparison of CFD Validation Approaches for Heat Transfer Coefficients

| Validation Approach | Application Context | Reported Accuracy | Key Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1D Analytical Comparison [34] | Multi-mini-channel module with FC-72/water | 13.5% - 29% difference from CFD | Computational simplicity; Good for initial design estimates | Less accurate for complex, three-dimensional flows |

| Infrared Thermography + FEA [35] | High-pressure water descaling | 5% temperature deviation (ΔT) in validation | Direct surface temperature measurement; Well-suited for industrial processes | Requires optical access to surface; Emissivity calibration needed |

| Convective Correlation Validation [36] | Rotating disk in still fluid | < 3% difference for low angular velocities | High accuracy for canonical problems; Well-established theory | Limited to specific, well-defined geometries and flow regimes |

| Surrogate CNN Models [37] | Impinging jet arrays with dynamic control | NMAE < 2% on validation data | Real-time prediction capability; Handles vast parameter spaces | Requires extensive CFD dataset for training; Black-box nature |

| Classic Cp Plot Comparison [38] | ONERA M6 wing external aerodynamics | Includes measurement error (±0.02) | Standardized, widely understood methodology | Primarily for aerodynamic forces, not directly for HTC |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for CFD Validation

Multi-Mini-Channel Heat Transfer Analysis

Recent research conducted at Kielce University of Technology provides a comprehensive protocol for validating CFD simulations of heat transfer in complex mini-channel systems [34]. The experimental apparatus consisted of a test section inclined at 165 degrees relative to the horizontal plane, containing twelve rectangular mini-channels (six hot and six cold) with a hydraulic diameter of 2.77 mm (140 mm length, 18.3 mm width, 1.5 mm depth). The heating system employed a halogen heating lamp on the top wall of external heated copper. The key experimental steps included:

- Flow Configuration: Establishment of steady-state countercurrent flow of Fluorinert FC-72 and distilled water through the separate hot and cold mini-channel sets.

- Temperature Measurement: Utilization of an infrared camera to measure the external temperature distribution on the heated mini-channel wall under stable thermal conditions.

- Data Reduction: Calculation of local heat transfer coefficients (HTCs) at multiple critical interfaces (heated plate-HMCHs, HMCHs-separating plate, separating plate-CMCHs, CMCHs-closing plate) using a one-dimensional (1D) analytical approach.

- CFD Simulation Setup: Implementation of parallel simulations in Simcenter STAR-CCM+ (version 2020.2.1) incorporating empirical boundary conditions and parameters (temperature, pressure, velocity profiles, heat flux density) measured during experiments.

- Validation Metric: Quantitative comparison of HTC values predicted by CFD against those derived from the 1D analytical method applied to experimental data, resulting in differences ranging from 13.5% to 29% across different channel interfaces [34].

High-Pressure Water Descaling HTC Prediction

An industrial-scale validation methodology was employed to develop a predictive HTC model for high-pressure water descaling processes, integrating CFD, finite element analysis (FEA), and infrared thermography [35]. The protocol systematically converted operational parameters into measurable heat transfer effects:

- Parameter Conversion: Operational variables (water flow rate, nozzle-to-billet standoff distance, nozzle geometry, installation configuration) were mathematically converted into water flux (ω) using the equation: ω = Q/F, where Q represents flow from a single nozzle and F is the coverage area calculated from jet impingement geometry [35].

- CFD Parametric Analysis: Computational fluid dynamics simulations were performed to quantitatively assess the HTC across a wide range of water flux and billet surface temperature values.

- Model Development: A mathematical model for HTC was developed through nonlinear regression analysis of the CFD results, establishing a predictive relationship between process parameters and heat transfer characteristics.

- FEA Implementation: The regression-derived HTC values were implemented in finite element analysis to simulate thermal profiles during the descaling process using actual production parameters.

- Experimental Validation: Real-time infrared thermography measurements of billet surface temperature were conducted during industrial-scale descaling operations. Comparison between simulated and measured temperatures showed a maximum discrepancy of 28°C and a minimum of 1°C, confirming the predictive accuracy of the model with less than 5% deviation at each measurement point [35].

Impinging Jet Array Surrogate Modeling

For complex active cooling systems with dynamically reconfigurable jet arrays, a novel protocol combining high-fidelity CFD with machine learning was developed to enable real-time prediction capabilities [37]:

- CFD Dataset Generation: Implicit large eddy simulations (Re < 2,000) were performed for a vast number of possible jet arrangements (inlet/outlet/shut states) in both five-by-one and three-by-three array configurations.

- Mesh Independence Verification: A comprehensive mesh sensitivity analysis was conducted to ensure results were independent of computational mesh density.

- Surrogate Model Training: A convolutional neural network (CNN) was trained on the time-averaged CFD results to predict Nusselt number distributions for any jet configuration.

- Reynolds Number Extrapolation: Predictions were extended to higher Reynolds numbers (Re < 10,000) using a correlation-based scaling method adapted from Martin's correlation [37].

- Performance Validation: The surrogate model achieved exceptionally high accuracy, with normalized mean average error (NMAE) below 2% for the five-by-one array and 0.6% for the three-by-three array on validation data, while maintaining real-time prediction capability unattainable with direct CFD simulation [37].

Workflow Diagram: CFD Validation Methodology

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and workflow between different CFD validation methodologies discussed in this guide, highlighting their interconnectedness in transfer coefficient calculation research.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Software

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for HTC Validation Studies

| Tool/Software | Specific Function | Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Simcenter STAR-CCM+ | Commercial CFD software for multiphysics simulation | Used for mini-channel simulations with FC-72/water [34] |

| Infrared Camera | Non-contact temperature measurement on heated surfaces | Measured external wall temperature in mini-channel study [34] and billet temperature in descaling research [35] |

| Fluorinert FC-72 | Dielectric coolant for electronic thermal management | Working fluid in multi-mini-channel experiments [34] |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | Machine learning architecture for spatial pattern recognition | Surrogate model for predicting Nusselt distribution in jet arrays [37] |

| High-Pressure Water Nozzle | Generates controlled impingement jets for descaling | Key component in water flux conversion and HTC modeling [35] |

| ADINA Software | Alternative commercial CFD package for heat transfer | Used in previous Kielce University research [34] |

| Finite Element Analysis (FEA) Software | Numerical simulation of temperature fields | Implemented HTC values to predict thermal profiles during descaling [35] |

The validation of Computational Fluid Dynamics for predicting localized heat transfer coefficients requires a strategic approach tailored to the specific application context and performance requirements. For canonical problems with established correlations, such as rotating disks, traditional validation against empirical formulas provides exceptional accuracy (<3% error) [36]. For complex industrial processes like descaling, the integration of CFD with infrared thermography and FEA delivers practical validation with acceptable field deviations (<5% ΔT) [35]. In applications requiring real-time prediction across vast parameter spaces, such as dynamic jet array control, surrogate CNN models offer a breakthrough with minimal error (<2% NMAE) while overcoming computational limitations [37]. Multi-mini-channel systems demonstrate that even simpler 1D analytical methods provide valuable validation benchmarks (13-29% range) when complemented with detailed experimental IR thermography [34]. The researcher's selection of validation methodology should therefore balance computational cost, accuracy requirements, operational constraints, and the availability of experimental validation data specific to their thermal system of interest.

The accurate prediction of complex parameters is a cornerstone of scientific advancement, particularly in fields involving intricate physical or biological systems. Traditional methodologies, often reliant on empirical correlations and linear statistical models, have long served as the primary tools for estimating key metrics. However, these approaches frequently struggle with accuracy and generalizability, especially when faced with complex, non-linear interactions among multiple parameters. In the specific context of transfer coefficient calculation methodologies—a critical aspect of thermal engineering, drug discovery, and clinical decision-making—these limitations have become increasingly apparent, creating a growing demand for more flexible and robust prediction methods [20] [39].

Machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) have emerged as transformative solutions to these challenges, offering innovative approaches that learn complex nonlinear relationships directly from data. Unlike traditional correlations that require a priori hypotheses about parameter relationships, ML models adaptively capture patterns from observational or experimental data, enabling more accurate predictions across diverse conditions. This capability is particularly valuable for modeling phenomena like boiling heat transfer, soil carbon mapping, and clinical outcomes where multiple interacting factors create complex system behaviors that defy simple parameterization [20] [40].