Solving Electrochemical System Degradation: Advanced Strategies for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of electrochemical system degradation, a critical challenge impacting device longevity and data integrity in research and diagnostics.

Solving Electrochemical System Degradation: Advanced Strategies for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of electrochemical system degradation, a critical challenge impacting device longevity and data integrity in research and diagnostics. It explores foundational degradation mechanisms—from electrode fouling to catalyst poisoning—and surveys advanced mitigation methodologies, including novel electrode materials and bioelectrochemical hybrids. The scope extends to practical troubleshooting protocols, system optimization frameworks, and rigorous validation techniques using statistical metrics and computational modeling. Designed for scientists and development professionals, this review synthesizes current research to equip readers with strategies for enhancing the reliability and performance of electrochemical systems in biomedical applications.

Understanding Electrochemical Degradation: Mechanisms and Sources of System Failure

Defining Electrochemical System Degradation and Key Performance Metrics

Electrochemical degradation refers to the deterioration of materials and the decline in system performance caused by electrochemical reactions. At its core, this process involves redox reactions where electrons are transferred, leading to the breakdown of material structure [1]. This phenomenon is not limited to metal corrosion but affects a wide range of materials including polymers, ceramics, and semiconductors when exposed to environments that facilitate electron transfer [1].

In sustainable technologies like batteries and fuel cells, electrochemical degradation manifests as gradual performance decline over time, directly affecting energy storage capacity, power output, and operational lifespan [2]. Understanding these degradation mechanisms is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals who rely on consistent electrochemical system performance for accurate measurements and experimental reproducibility.

Fundamental Degradation Mechanisms

Core Principles and Components

Electrochemical degradation requires three fundamental components that form an electrochemical cell [1]:

- Anode: The site where oxidation occurs, material loses electrons and dissolves or forms ions

- Cathode: The location where reduction occurs, another substance gains electrons

- Electrolyte: A medium that allows ions to move between anode and cathode, completing the electrical circuit

Common Forms of Electrochemical Degradation

Different manifestations of electrochemical degradation present unique challenges in research settings [1]:

Table: Common Forms of Electrochemical Degradation

| Degradation Type | Characteristics | Impact on Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Uniform Corrosion | Relatively even material loss across exposed surfaces | Gradual signal drift, changing baseline responses |

| Galvanic Corrosion | Preferential corrosion of more active metal when dissimilar metals contact | Localized failure at connection points, unexpected potential shifts |

| Pitting Corrosion | Highly localized formation of small, deep pits | Sudden, catastrophic failures; difficult to predict |

| Crevice Corrosion | Occurs in narrow gaps where stagnant electrolyte accumulates | Common in assembly joints; causes erratic behavior |

| Electrochemical Wear | Accelerated material loss in tribological systems with electrolyte present | Affects moving parts in specialized electrochemical cells |

Key Performance Metrics for Monitoring Degradation

Tracking electrochemical system health requires monitoring specific, quantifiable metrics that indicate degradation progression. The following performance parameters are essential for diagnosing system status:

Table: Key Performance Metrics for Electrochemical System Health

| Performance Metric | Measurement Technique | Indication of Degradation |

|---|---|---|

| Charge Transfer Resistance (Rct) | Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) | Increasing values indicate deteriorating electrode performance [3] |

| Ohmic Resistance (Ro) | Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) | Rising values suggest connection issues or electrolyte problems [3] |

| Power Output | Chronoamperometry/Voltammetry | Decreasing output signals reduced system efficiency [3] |

| Cycle Life | Repeated charge/discharge cycles | Fewer sustainable cycles indicate accelerated degradation |

| Voltage Compliance | Potentiostat error monitoring | Inability to maintain set potential suggests system resistance issues [4] |

| Current Compliance | Potentiostat error monitoring | Unexpected current surges indicate short circuits or connection problems [4] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Signal analysis | Decreasing ratio suggests electrode surface degradation or connection issues [5] |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

General Troubleshooting Procedure

When facing abnormal electrochemical measurements, follow this systematic approach to isolate the problem source [6] [4]:

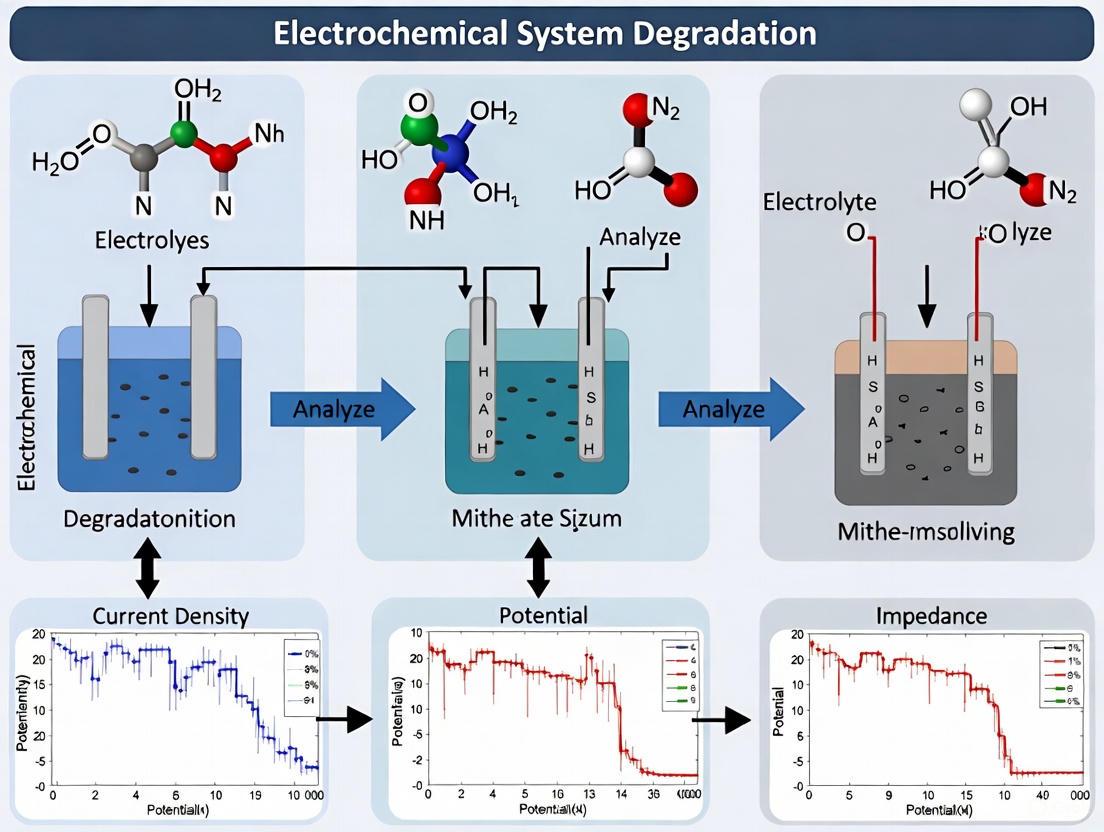

Systematic troubleshooting workflow for electrochemical systems

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: My potentiostat shows "voltage compliance" errors. What does this mean and how can I resolve it?

A: Voltage compliance errors indicate the potentiostat cannot maintain the desired potential between working and reference electrodes. This typically occurs when [4]:

- The reference electrode is not properly connected or has a clogged frit

- The counter electrode has been removed from solution or disconnected

- A quasi-reference electrode is touching the working electrode Check all electrode connections and ensure proper immersion in electrolyte. For reference electrodes, verify the salt-bridge/frit isn't blocked and no air bubbles are trapped at the bottom.

Q: I observe significant noise in my measurements. How can I reduce this interference?

A: Excessive noise often stems from poor electrical contacts or environmental interference [6]:

- Check and polish all lead connections to remove rust or tarnish

- Ensure secure connections at the instrument connector

- Place the electrochemical cell inside a Faraday cage to shield from external electromagnetic interference

- Verify electrode stability in solution without loose connections

Q: My cyclic voltammograms show unusual peaks not attributable to my analyte. What could cause this?

A: Unexpected peaks can originate from multiple sources [4]:

- Impurities in electrolytes, solvents, or from system components

- Edge effects as the scanning potential approaches the system's potential window limits

- Degradation products from system components or the analyte itself Run a background scan without analyte to identify system-related peaks, and ensure all chemicals and materials are of appropriate purity.

Q: The baseline in my voltammograms is not flat and shows significant hysteresis. What is the cause?

A: Baseline hysteresis primarily results from charging currents at the electrode-solution interface, which acts as a capacitor [4]. To minimize this effect:

- Reduce the scan rate

- Increase analyte concentration

- Use a working electrode with smaller surface area Additionally, check for working electrode faults such as poor internal contacts or glass walls between connections that can exacerbate this issue.

Experimental Protocols for Degradation Assessment

Machine Learning-Enhanced Multi-Electrode Assessment

Recent advances enable more sophisticated degradation monitoring through multi-electrode systems and machine learning [7]:

Objective: To identify and quantify degradation in complex samples through electrochemical fingerprinting and machine learning analysis.

Materials and Equipment:

- Multi-electrode system (Cu, Ni, and C working electrodes sharing a Cu counter electrode)

- Potentiostat with multi-channel capability

- Standard reference electrode

- Electrolyte solution appropriate for your system

- Machine learning environment (Python with scikit-learn, TensorFlow, or similar)

Procedure:

- Prepare electrode system with Cu, Ni, and C working electrodes

- Record cyclic voltammograms for standard samples across all electrodes

- Convert CV curves (current vs. potential) to current-time data

- Extract features (e.g., 1040 current values per voltammogram)

- Train machine learning model (Decision Trees, Random Forests, or Neural Networks) using known samples

- Validate model with test samples of known composition

- Apply to unknown samples to detect and quantify degradation markers

Data Analysis:

- Combine signals from different electrodes to create electrochemical fingerprints

- Use appropriate data segmentation (typically 80:20 or 90:10 training:validation ratio)

- Evaluate model performance through confusion matrices and classification accuracy

This approach has successfully identified antibiotic degradation in milk samples with classification accuracies of 0.8-1.0 for five antibiotics, demonstrating the power of combined electrochemical and machine learning techniques [7].

Dummy Cell Validation Procedure

Regular instrument validation is essential for reliable degradation monitoring [6] [4]:

Objective: Verify proper operation of potentiostat and leads independently from the electrochemical cell.

Materials:

- Potentiostat with connection cables

- 10 kΩ resistor (dummy cell)

- Standard measurement software

Procedure:

- With the potentiostat turned off, disconnect the electrochemical cell

- Connect the reference and counter electrode leads to one side of the 10 kΩ resistor

- Connect the working electrode lead to the other side of the resistor

- Perform a CV scan from +0.5 V to -0.5 V at 100 mV/s scan rate

- Analyze the resulting scan

Expected Results:

- A correct response shows a straight line intersecting the origin

- Current values should follow Ohm's law (V = IR) with maximum currents of ±50 μA

- Deviation from this response indicates issues with the instrument or leads requiring service

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Proper selection of materials and reagents is fundamental to controlling electrochemical degradation in experimental systems:

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Electrochemical Systems

| Item | Function/Purpose | Degradation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Electrodes (Ag/AgCl, Calomel) | Provide stable potential reference | Clogged frits create instability; regular inspection required [6] |

| Counter Electrodes (Pt wire, graphite) | Complete electrical circuit without interference | May require cleaning or polishing to maintain performance |

| Working Electrodes (GC, Au, Pt) | Primary measurement interface | Surface degradation significantly impacts results; require regular polishing [4] |

| Electrolyte Salts (KCl, NaClO₄, TBAPF₆) | Provide ionic conductivity | Impurities introduce artifacts; purity critical for reliable results |

| Solvents (Acetonitrile, DMF, Water) | Dissolve analyte and electrolyte | Residual water or impurities affect potential windows and reactivity |

| Alumina Polishing Suspensions (0.05 μm) | Maintain electrode surface condition | Regular polishing essential to prevent surface fouling effects [4] |

| Faraday Cages | Electromagnetic interference shielding | Critical for reducing noise in sensitive measurements [6] |

| Quasi-Reference Electrodes (Ag wire) | Alternative reference when standard electrodes fail | Less stable but useful for troubleshooting [4] |

Advanced Monitoring: Machine Learning in Degradation Analysis

Machine learning techniques are increasingly valuable for predicting and analyzing electrochemical system degradation. These approaches can process complex, multidimensional electrochemical data to identify degradation patterns that may not be apparent through traditional analysis [7].

For microbial electrochemical systems, models like XGBoost, Random Forest, Support Vector Regression, and Neural Networks have successfully predicted system performance degradation based on anode characteristics. Feature importance analysis reveals that charge transfer resistance (Rct), ohmic resistance (Ro), and anode thickness are critical factors influencing degradation rates and system longevity [3].

The implementation of machine learning in degradation monitoring follows a structured workflow:

Machine learning workflow for electrochemical degradation prediction

This approach is particularly valuable for predicting long-term degradation in complex systems like microbial fuel cells and battery systems, where multiple interdependent factors contribute to performance decline [3].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between electrode fouling and passivation? While both fouling and passivation lead to a loss of electrode activity, their underlying mechanisms differ. Fouling typically refers to the physical accumulation or adsorption of unwanted materials (like organic molecules, biomolecules, or precipitates) on the electrode surface, which blocks active sites and impedes mass transport [8] [9]. Passivation, however, involves the formation of a chemically bonded, often compact, oxide or hydroxide layer on the electrode surface [10] [11]. This layer acts as a physical barrier that severely limits charge transfer and species transport, leading to a sharp drop in anodic current [11].

Q2: How does chloride ion addition help mitigate passivation in electrocoagulation systems? Introducing chloride ions (Cl⁻) is a common strategy to mitigate anode passivation in electrocoagulation (EC). Chloride ions compete with hydroxide ions (OH⁻) at the anode surface, facilitating the pitting of the passive film and promoting its disintegration. This process helps to maintain the active dissolution of the sacrificial anode (like iron or aluminum), ensuring a steady supply of metal coagulants for the treatment process [10].

Q3: Can passivation ever be a desirable phenomenon? Yes, in the context of corrosion control, passivation is highly desirable. The formation of a dense, stable passive film, such as a chromium-rich oxide layer on stainless steel, protects the underlying metal from further corrosive attack, significantly enhancing its durability [11].

Q4: Why do my electrochemical measurements show unusual kinetics or a continuous drop in signal? This is a classic symptom of a fouling or passivation process occurring at the electrode surface. For instance, during the oxidation of molecules like 4-hydroxy-TEMPO, a polymeric passivation layer can form on the electrode, altering the reaction kinetics and reducing signal over time [8]. Similarly, the detection of neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine can lead to chemical fouling from oxidative by-products, which adsorb to the electrode and decrease its sensitivity [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Performance Degradation Comparison

Table 1: Characterizing and Differentiating Key Failure Modes

| Failure Mode | Primary Cause | Key Characteristics | Common Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrode Fouling | Accumulation of organic molecules, biomolecules, or salts [8] [9]. | • Decreased sensitivity and current output [9].• Can be non-conductive or conductive. | • Polishing/cleaning the electrode surface [8].• Applying protective surface coatings (e.g., PEDOT:PSS, PEDOT:PC) [9].• Optimizing operating parameters (e.g., pulse current) [10]. |

| Catalyst Poisoning | Strong, specific chemisorption of a species (e.g., sulfides) onto active catalyst sites. | • Often irreversible or slowly reversible under operating conditions.• Primarily reduces reaction rate (kinetics). | • Purifying reactants/electrolytes to remove poisons.• Designing catalysts with selective active sites.• Implementing potential cycling to desorb poisons. |

| Passivation | Growth of a protective oxide/hydroxide film (e.g., on Fe, Al, Ti) [10] [11]. | • Sharp drop in anodic current (e.g., from mA to μA/cm²) [11].• Increased impedance and overpotential. | • Introducing aggressive anions (e.g., Cl⁻) to disrupt the film [10].• Applying alternating or pulse currents to periodically reduce the film [10].• Controlling electrolyte chemistry (e.g., pH, hydroxide concentration) [11]. |

Quantitative Impact of Failure Modes

Table 2: Measured Performance Loss in Electrochemical Systems

| System / Application | Failure Mode | Key Performance Metric | Impact of Failure | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reverse Osmosis (FES Disinfection) | Biofouling | Normalized Flux Drop | 67% reduction after 20-day operation [12]. | [12] |

| Iron in Alkaline Solution | Passivation | Passive Current Density (ip) | ip = 5×10⁻⁶ mA·cm⁻² at pH 8 [11]. | [11] |

| 4-OH-TEMPO Oxidation | Passivation | Electrode Activity | Formation of a polymeric passivation layer, suppressing current [8]. | [8] |

| Neurotransmitter Detection (FSCV) | Chemical Fouling | Sensitivity (DA Oxidation Current) | ~50% signal decrease after serotonin fouling [9]. | [9] |

Step-by-Step Diagnostic Protocol

Workflow: Diagnosing Electrode Degradation

Protocol: Diagnosing the Root Cause of Performance Loss

Initial Performance Assessment: Document the baseline performance metrics (e.g., current density, sensitivity, flux) and note the extent and rate of degradation.

Visual Inspection & Surface Analysis:

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS):

- Action: Perform EIS to characterize the electrode/electrolyte interface.

- Interpretation: A significant increase in charge-transfer resistance suggests passivation. An increase in film resistance from a porous layer is more indicative of fouling.

Potentiodynamic Polarization:

- Action: Run a polarization scan.

- Interpretation: A sharp, orders-of-magnitude drop in anodic current followed by a low-current plateau is characteristic of passivation [11]. A gradual current decrease often points to fouling.

Surface Cleaning Test:

- Action: Gently polish or clean the electrode surface chemically (e.g., with solvents or a mild acid).

- Interpretation: If performance is largely restored, the issue was likely fouling. If performance loss persists, the primary mechanism is likely passivation or strong catalyst poisoning [8].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Mitigating Passivation in Electrocoagulation via Polarity Reversal

This protocol details a method to mitigate passivation in electrocoagulation (EC) systems, a common issue that increases energy consumption and reduces efficiency [10].

Principle: Periodically reversing the current polarity prevents the continuous build-up of a passivating oxide/hydroxide layer on the anode surface, promoting a more consistent electrode dissolution [10].

Materials:

- Electrodes: Iron (e.g., mild steel) or Aluminum plates.

- Power Supply: Programmable DC power supply capable of automatic polarity reversal.

- Reactor: A beaker or custom EC cell.

- Wastewater: Synthetic or real wastewater sample.

- Data Acquisition: Voltmeter to monitor cell voltage.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Electrode Preparation: Clean the electrode plates by polishing with abrasive paper (e.g., sequentially from 600 to 1200 grit). Rinse thoroughly with deionized water [13].

- Reactor Setup: Arrange the electrodes in parallel in the reactor with a fixed spacing (e.g., 5-20 mm). Fill the reactor with the wastewater sample. Place the reactor on a magnetic stirrer to ensure mixing [10] [13].

- Parameter Setting: Set the desired current density (a typical range is 10-50 A/m²). Program the power supply to reverse polarity at a fixed time interval (e.g., switch the anode and cathode roles every 30 to 120 seconds) [10].

- Process Operation: Start the power supply and the magnetic stirrer. Record the initial cell voltage.

- Monitoring: Monitor the cell voltage throughout the experiment. A stable or slowly increasing voltage indicates effective passivation control, while a rapid voltage rise suggests that the mitigation strategy needs optimization (e.g., shorter switching intervals).

- Analysis: After a set duration, analyze the treated water for contaminant removal efficiency (e.g., measure UV-Vis absorbance or chemical oxygen demand). Compare the final electrode surfaces to a control experiment run without polarity reversal.

Protocol: Evaluating Chemical Fouling during Neurotransmitter Detection

This protocol simulates and evaluates chemical fouling on carbon fiber microelectrodes (CFMEs) used in biological sensing, a key challenge for accurate measurement [9].

Principle: Neurotransmitters like serotonin (5-HT) form oxidative by-products that strongly adsorb to carbon surfaces, reducing active sites and hindering electron transfer, which manifests as a loss in detection sensitivity [9].

Materials:

- Working Electrode: Carbon Fiber Microelectrode (CFME).

- Reference Electrode: Ag/AgCl.

- Electrochemical Workstation: Capable of Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry (FSCV).

- Chemicals: Serotonin (5-HT) or Dopamine (DA) stock solution, Tris buffer.

- Setup: Standard electrochemical cell.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Electrode Stabilization: Place the CFME and reference electrode in a Tris buffer solution. Apply the "Jackson" waveform (0.2 V → 1.0 V → -0.1 V → 0.2 V at 1000 V/s) at 10 Hz for 10-15 minutes until a stable background current is achieved [9].

- Baseline Measurement: Record several FSCV cycles in fresh Tris buffer to establish a stable baseline.

- Fouling Induction: Immerse the electrodes in a Tris buffer solution containing 25 µM serotonin. Continue applying the Jackson waveform for 5 minutes to induce fouling [9].

- Post-Fouling Measurement: Return the electrodes to the fresh Tris buffer solution. Again, record FSCV cycles using the same waveform.

- Data Analysis:

- Compare the oxidation current of a standard dopamine (or serotonin) dose before and after the fouling step.

- Calculate the percentage loss in sensitivity:

% Loss = [1 - (I_post / I_pre)] * 100. - Note any shifts in the peak potential, which also indicate surface fouling [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Fouling and Passivation Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS / PEDOT:PC Coatings | Conductive polymer coatings for CFMEs to reduce biomolecule adsorption (biofouling) [9]. | Excellent biocompatibility and antifouling properties for in vivo sensing. |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | Adding Cl⁻ ions to electrolytes to disrupt and pit passive films on metal anodes [10]. | Concentration must be optimized; too low is ineffective, too high may cause corrosion. |

| Alternating Pulse Current (APC) Power Supply | Prevents passivation by periodically dissipating the double layer and reversing reactions [12] [10]. | More effective than DC for biofouling control in systems like Flow-through Electrode Systems (FES) [12]. |

| Zinc Oxide (ZnO) Coated Electrodes | Nanomaterial coating for electrodes to enhance coagulation efficiency and potentially reduce fouling [13]. | Improves charge transfer and can offer catalytic properties. |

| Alumina Polishing Slurries (1, 0.3, 0.05 µm) | For mechanically removing fouling layers or passivation films from electrode surfaces [8]. | Sequential polishing with finer grits is essential for restoring a mirror-like surface. |

| 4-Hydroxy-TEMPO (HT) | A redox-active organic molecule for flow battery research that is known to cause electrode passivation [8]. | Serves as a model compound for studying passivation mechanisms in organic electrolytes. |

Theoretical Foundations of Loss Mechanisms

In electrochemical systems, performance losses that lead to degradation and efficiency decay are categorized into three fundamental types: kinetic, ohmic, and mass transport limitations. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for diagnosing and mitigating degradation in research experiments.

What are the fundamental origins of voltage losses in my electrochemical cell?

Voltage losses in electrochemical systems arise from three primary sources, each with distinct characteristics and operational dependencies:

Kinetic Losses (Activation Overpotential): These losses occur due to the energy barrier of the electrochemical reaction at the electrode-electrolyte interface. They dominate at low current densities and are particularly sensitive to catalyst composition, surface structure, and operational temperature. The Butler-Volmer equation fundamentally describes the relationship between current density and activation overpotential [14].

Ohmic Losses (Resistive Overpotential): These losses result from resistance to electron flow through conductors and ion flow through the electrolyte. They exhibit a linear relationship with current density according to Ohm's Law (η_ohmic = I × R). Ohmic losses are strongly influenced by material conductivity, interfacial contacts, and cell architecture [15].

Mass Transport Losses (Concentration Overpotential): These losses emerge when reactant supply to or product removal from electrode surfaces becomes limited. They typically manifest at high current densities and are characterized by a rapid voltage drop. Mass transport limitations are governed by diffusion, convection, and migration processes within the electrolyte and porous electrode structures [15].

Table 1: Characteristics of Fundamental Loss Mechanisms in Electrochemical Systems

| Loss Mechanism | Dominant Operating Region | Primary Influencing Factors | Voltage-Current Relationship |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinetic | Low current density | Catalyst activity, temperature, reaction mechanism | Exponential (Butler-Volmer) |

| Ohmic | All current densities, linear effect | Material conductivity, interfacial contacts, cell design | Linear (Ohm's Law) |

| Mass Transport | High current density | Reactant concentration, flow field design, diffusion media properties | Rapid increase near limiting current |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Troubleshooting Electrochemical Performance Degradation

Why has my cell voltage increased significantly after extended operation?

Performance decay in electrochemical cells often results from interconnected degradation mechanisms. The following troubleshooting guide provides a systematic approach to diagnose these issues:

Systematic Diagnosis Procedure:

Perform Current-Voltage Characterization: Measure full polarization curves from open circuit to maximum operational current and compare with baseline performance [15].

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) Analysis: Conduct EIS measurements across multiple current densities to deconvolute kinetic, ohmic, and mass transport contributions to performance loss [14].

Reference Electrode Diagnostics: Utilize a reference electrode to isolate anode and cathode overpotentials, identifying which electrode is primarily responsible for performance decay [6].

Post-Test Material Characterization: Employ ex situ analysis techniques such as SEM, TEM, XPS, or ICP-MS to identify material degradation, dissolution, or contamination [16].

My current distribution has become non-uniform. What could be causing this issue?

Non-uniform current distribution significantly accelerates localized degradation and often precedes catastrophic failure:

Flow Field Blockages: Particulate contamination or gas bubble accumulation can obstruct flow channels, creating regions with limited reactant access and elevated local current densities [15].

Diffusion Media Degradation: Compression variations, mechanical damage, or corrosion of porous transport layers (PTLs) can create preferential pathways for current flow [17].

Catalyst Layer Inhomogeneity: Localized catalyst dissolution, support corrosion, or ionomer degradation creates regions with varying catalytic activity, forcing current to concentrate in more conductive areas [16].

Thermal Gradients: Inadequate thermal management creates temperature variations that significantly impact local reaction kinetics and material properties [14].

Table 2: Diagnostic Solutions for Current Distribution Issues

| Problem Symptom | Diagnostic Method | Expected Observation | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Channel-Specific Performance Variation | Segmented current measurement | >20% current variation between parallel channels | Inspect for flow obstructions; verify manifold distribution |

| Gradual Current Maldistribution | Periodic EIS mapping | Increasing variation in local impedance spectra | Check compression uniformity; inspect PTL for damage |

| Inlet-Outlet Gradient | Local electrochemical measurement | Higher current density at inlet decreasing toward outlet | Optimize flow rate; consider flow field redesign |

| Random Hot Spots | Thermal imaging | Local temperature elevations >5°C above average | Verify catalyst layer uniformity; check for contaminants |

Experimental Protocols for Degradation Analysis

Protocol 1: Accelerated Stress Testing (AST) for Catalyst Stability

Objective: Evaluate electrochemical stability of catalyst materials under accelerated degradation conditions [16].

Materials and Equipment:

- Potentiostat/Galvanostat with electrochemical impedance capability

- Electrochemical cell with temperature control

- Reference electrode (e.g., RHE) and counter electrode

- Catalyst-coated working electrode (typically rotating disk electrode)

- High-purity electrolyte solution

- Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) system (optional)

Procedure:

- Initial Electrochemical Characterization:

- Measure initial electrochemical surface area (ECSA) via cyclic voltammetry

- Record baseline polarization curve

- Perform electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS)

Accelerated Stress Testing:

- Apply potential cycling (e.g., 10,000 cycles between 0.58-1.41 V versus RHE at 1 V/s)

- Alternatively, apply constant high potential hold

- Maintain precise temperature control (±1°C)

- Use continuous electrolyte purging with inert gas

Post-Test Analysis:

- Measure ECSA loss after AST

- Quantify metal dissolution via ICP-MS of electrolyte

- Characterize catalyst structure via identical location TEM/SEM

- Correlate electrochemical performance decay with physical characterization

Interpretation: ECSA loss >40% indicates significant catalyst degradation. Minor mass loss with substantial ECSA reduction suggests particle growth via Ostwald ripening, while significant mass loss indicates dissolution as the primary mechanism [16].

Protocol 2: Mass Transport Limitation Analysis

Objective: Quantify mass transport contributions to voltage losses and identify limiting components [15].

Materials and Equipment:

- Electrochemical test station with current distribution mapping capability

- Custom cell with segmented current measurement (e.g., S++ board)

- Reference electrode array

- Flow control system with precise flow rate regulation

- High-speed visualization capability (optional)

Procedure:

- Current Distribution Mapping:

- Install segmented current measurement system

- Measure local current densities at multiple operating points

- Generate 2D current distribution maps

Flow Rate Dependency Analysis:

- Measure polarization curves at multiple flow rates (e.g., 0.5-5× stoichiometric ratio)

- Quantify voltage loss dependence on flow rate

- Identify transition point where mass transport limitations dominate

Operando Visualization:

- Utilize transparent cell sections for bubble observation

- Employ high-speed camera for bubble dynamics analysis

- Correlate bubble behavior with local current density

Post-Test Component Analysis:

- Examine diffusion media for pore blockage

- Analyze flow fields for obstruction or corrosion

- Characterize catalyst layer structural changes

Interpretation: Strong flow rate dependence indicates mass transport limitations. Uneven current distribution suggests maldistribution issues. Correlation between bubble accumulation and current density reduction confirms two-phase flow limitations [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Degradation Studies

| Material/Reagent | Function in Research | Degradation Relevance | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nafion Ionomer | Proton conductor in catalyst layers | Chemical degradation under radical attack | Thickness affects gas crossover; processing impacts stability |

| Vulcan XC-72 Carbon | Catalyst support material | Corrosion at high potentials (>1.0 V) | Surface chemistry affects catalyst stability; surface area influences dispersion |

| Pt/C, Au/C Catalysts | Benchmark electrocatalysts | Dissolution, ripening, agglomeration | Particle size distribution impacts stability; smaller particles more susceptible |

| Ti Porous Transport Layers | Anode diffusion media | Passivation, coating dissolution | Pt coating prevents passivation but introduces dissolution risk [17] |

| Ag/AgCl Reference Electrode | Potential measurement | Clogging, contamination | Frit condition critical for stability; requires regular validation [6] |

| 0.1 M H₂SO₄ Electrolyte | Standard acidic electrolyte | Contaminant introduction | Chloride impurities accelerate dissolution; purity is critical [16] |

Advanced Diagnostic Visualization Techniques

Integrating Multiple Diagnostics: Advanced degradation analysis requires correlating multiple characterization techniques to establish complete mechanistic understanding. Combining electrochemical flow cell ICP-MS with identical location TEM allows direct correlation between dissolution events and nanostructural changes [16]. Similarly, coupling current distribution mapping with operando visualization techniques enables identification of localized mass transport limitations [15]. These correlated approaches move beyond simple performance monitoring to provide fundamental understanding of degradation pathways essential for developing mitigation strategies.

FAQ: What are PFAS and why are they a problem for electrochemical research?

Answer: Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a group of over 4,000 human-made chemicals used in various industrial and consumer products since the 1940s due to their oil- and water-repelling properties [18] [19]. A key characteristic of PFAS is the strong carbon-fluorine (C-F) bond, one of the strongest in organic chemistry, which makes these compounds highly persistent in the environment and resistant to conventional degradation processes [20]. For researchers, this persistence and the compounds' widespread presence pose a significant challenge, as they can interfere with experiments, cause background contamination in analytical procedures, and are difficult to completely eliminate from experimental systems, especially in studies focused on electrochemical degradation or environmental remediation [21].

Answer: PFAS can enter the research environment and experimental matrices through numerous pathways, which must be understood to prevent contamination. The table below summarizes the major sources and pathways relevant to laboratory settings.

Table 1: Key Sources and Pathways of PFAS Contamination

| Source Category | Specific Examples | Potential Research Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Industrial & Commercial Products | Aqueous film-forming foams (AFFF), metal plating, textiles, paper packaging [18] [19] | Contamination of water or soil samples collected from impacted sites. |

| Consumer Goods | Non-stick cookware, stain-resistant carpets/fabrics, food packaging, some cosmetics [19] | Laboratory background contamination from dust or airborne particles. |

| Environmental Media | Contaminated drinking water, soil, air, seafood, and biosolids (fertilizer) [18] [19] | Introduction of PFAS into experiments via reagents, solvents, or water. |

PFAS are mobile and can be transported long distances. Exposure in a lab context can occur through ingestion of contaminated water/food, inhalation of indoor air, or contact with dust from PFAS-containing products [18] [19]. For experimental integrity, it is critical to be aware that direct exposures from products can be phased out, but indirect exposures from environmental accumulation persist for decades [18].

FAQ: My electrochemical system is showing unexpected results. How do I troubleshoot it?

Answer: Follow this systematic troubleshooting guide to isolate the problem. The diagram below outlines the logical workflow for diagnosing common issues in a three-electrode electrochemical cell.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Dummy Cell Test: Disconnect your electrochemical cell and replace it with a 10 kΩ resistor. Connect the reference and counter electrode leads to one side and the working electrode lead to the other. Run a CV scan from +0.5 V to -0.5 V at 100 mV/s. The result should be a straight line intersecting the origin with currents of ±50 μA [6].

- Incorrect Response: The problem lies with your potentiostat, cables, or connections. Check cable continuity or replace them [6].

- Correct Response: The instrument is fine; the problem is with the electrochemical cell itself. Proceed to the next step.

- Two-Electrode Test: Reconnect the cell, but connect both the reference and counter electrode leads to the counter electrode. Run the CV again. If the response now looks like a typical voltammogram, the issue is with your reference electrode (e.g., clogged frit, air bubble, or poor contact) [6].

- Working Electrode Check: If the response in the two-electrode test is still poor, ensure all electrodes are properly immersed and that internal leads are intact. The problem is likely with your working electrode surface, which may be fouled, degraded, or insulated. Recondition the electrode by polishing or chemical/electrochemical cleaning [6].

- Noce Reduction: If your data is noisy, check for poor electrical contacts (rust, tarnish) and ensure all connectors are clean. Placing the cell inside a Faraday cage can also significantly reduce electrical noise [6].

FAQ: How can I prevent PFAS contamination during environmental sampling for my experiments?

Answer: Due to the ubiquity of PFAS and their very low (parts-per-trillion) action levels, a highly rigorous and conservative sampling protocol is essential to avoid cross-contamination [21]. Key considerations are outlined in the table below.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for PFAS Sampling & Analysis

| Item / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Critical Considerations to Prevent Bias |

|---|---|---|

| PFAS-Free Water | Used for field blank QC, equipment rinsing, and solution preparation [21]. | Must be supplied and certified by the analytical laboratory. Verify documentation to confirm it meets project "PFAS-free" definition [21]. |

| Sample Bottles | Containment and preservation of water samples [21]. | Use high-density polyethylene (HDPE) or polypropylene (PP). Avoid plastics containing "fluoro" or "halo" compounds [21]. |

| Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) | Protect researcher but must not contaminate sample [21]. | Avoid waterproof or stain-resistant clothing and gear. Use powder-free nitrile gloves [21]. |

| Field Equipment | Sampling pumps, tubing, etc. [21] | Review Safety Data Sheets (SDS) for all materials. Avoid any equipment where PFAS may have been used in manufacturing (e.g., as a mist suppressant) [21]. |

| Sample Preservation | Maintains sample integrity for accurate analysis [21]. | Follow the specific analytical method (e.g., EPA 537.1, 533, 1633) exactly. Methods are prescriptive and changes are prohibited [21]. |

Additional Protocols:

- Documentation: Maintain a detailed log of all materials used and their potential for PFAS content [21].

- Communication: Inform your analytical laboratory if samples are expected to be highly concentrated with PFAS to prevent cross-contamination of their instrumentation and other samples [21].

FAQ: What are the key analytical methods for detecting and quantifying PFAS?

Answer: The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has developed and validated several standardized methods for PFAS analysis in different matrices. The choice of method depends on your sample type and data quality objectives.

Table 3: Standardized Analytical Methods for PFAS

| Method Name | Applicable Matrices | Key Description | Number of PFAS Analyzed |

|---|---|---|---|

| EPA Method 533 | Drinking Water | Isotope dilution anion exchange solid-phase extraction (SPE) and LC/MS/MS [22]. | 25 [22] |

| EPA Method 537.1 | Drinking Water | Solid-phase extraction (SPE) and LC/MS/MS. Includes GenX chemicals [22]. | 18 [22] |

| EPA Method 1633A | Water, Soil, Sediment, Biosolids, Tissue | Sample preparation and analysis for a wide range of environmental media [21]. | 40 [22] |

| DOD AFFF01 | AFFF Concentrates | Determination of PFOA and PFOS in firefighting foam for specification compliance [21]. | Targeted for PFOA/PFOS |

It is important to understand the distinction between Targeted Analysis (which looks for a specific, predefined list of analytes using existing standards) and Non-Targeted Analysis (which uses high-resolution mass spectrometry to identify all known and unknown compounds in a sample) [22]. For most regulatory and definitive site characterization work, the targeted methods listed above are used.

FAQ: Can electrochemical degradation effectively treat PFAS, and what are the challenges?

Answer: Yes, electrochemical oxidation (EO) is a promising and advanced technology for the destruction of PFAS, particularly long-chain compounds like PFOA and PFOS [20]. Research has shown removal rates exceeding 99% for some long-chain PFAS [20].

Mechanism: The process utilizes electricity to generate powerful oxidizing agents (e.g., hydroxyl radicals •OH) directly in the water at the surface of the anode. These radicals can "scissor" long-chain PFAS molecules into shorter-chain intermediates, ultimately leading to defluorination (breaking the C-F bonds) and mineralization [20]. A significant advantage of EO is its ability to operate effectively in the presence of Natural Organic Matter (NOM), which often interferes with other treatment technologies [20].

Experimental Challenges and Considerations:

- Electrode Material: The choice of anode is critical. Boron-Doped Diamond (BDD) electrodes are often studied due to their high stability and efficiency in generating radicals [20].

- Competing Reactions: In complex water matrices, other substances can compete for the generated radicals, potentially reducing the treatment efficiency for the target PFAS compounds [20].

- Energy Consumption: Optimizing process parameters like current density and reaction time is essential to maximize destruction efficiency while minimizing energy costs [20].

- Byproduct Formation: The incomplete degradation of PFAS can lead to the formation of short-chain intermediates. A key goal of research is to achieve complete mineralization to fluoride ions (F⁻), carbon dioxide, and water [20].

Impact of Degradation on Data Accuracy and Experimental Reproducibility

Core Concepts and Definitions

What is the fundamental difference between accuracy and precision? Accuracy refers to the closeness of a single measurement to a true or reference value. Precision, or imprecision, describes the inconsistency or variation observed when the same sample is measured repeatedly under specified conditions. High precision (low imprecision) means repeated measurements yield very similar results, but this does not guarantee they are accurate. Accuracy is affected by both bias (a systematic deviation from the true value) and imprecision [23].

What are the different types of measurement variation? Variation in laboratory data is categorized based on the conditions under which it is measured [23]:

- Repeatability: Variation observed when measurements are taken in a short time interval using the same method, instruments, reagents, personnel, and location. This represents the smallest possible imprecision.

- Intermediate Precision: Variation observed over longer intervals (e.g., days, months) within the same laboratory, with potential changes in instruments, reagents, or personnel.

- Reproducibility: Variation observed when measurements are taken under different conditions, such as in different laboratories. This represents the largest degree of imprecision.

How does biological variation differ from analytical variation?

- Analytical Variation: This is the imprecision inherent to the measurement procedure itself (e.g., the laboratory instrument and reagents).

- Biological Variation: This is the inherent fluctuation of analytes in a patient's body due to the dynamic nature of metabolism. With advancements in technology, analytical imprecision can often be minimized to a level that is insignificant compared to biological variation [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Source of Data Variation

Problem: Inconsistent results when repeating an experiment or measurement.

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Check under Repeatability Conditions: Run the same sample multiple times in quick succession using the same equipment and reagents. | A small, consistent variation (low imprecision) indicates the core measurement process is stable. Large variation here suggests an immediate problem with instrument calibration, reagent stability, or sample handling. |

| 2 | Check under Intermediate Precision Conditions: Run the same sample over multiple days, using different instrument batches or operators. | An increase in variation compared to Step 1 pinpoints sources like reagent lot differences, operator technique, or instrumental drift over time. |

| 3 | Check Pre-analytical Factors: Review sample collection, handling, and storage protocols. | Identifying a deviation in pre-analytical steps (e.g., incorrect sampling time, sample degradation) explains variation unrelated to the analytical method itself. |

| 4 | Compare to Reproducibility Data: If possible, compare your results with those from an external laboratory. | A significant discrepancy suggests issues with the overall methodology or calibration that may not be apparent within a single lab. |

Guide 2: Addressing Electrode Degradation in Electrochemical Systems

Problem: Declining current density or Faradaic efficiency in an electrochemical CO₂ reduction (CO2R) system.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Gradual drop in performance | Catalyst Fouling/Deactivation | Implement periodic electrode cleaning protocols or use an integrated system for continuous product separation to prevent accumulation [24]. |

| Sudden, severe performance loss | Crossover of Reactants/Products | Check the integrity of ion-exchange membranes. In CO2R, carbonate (CO₃²⁻) formation and crossover can significantly reduce CO₂ utilization efficiency [24]. |

| Unstable voltage or current | Electrolyte Contamination or Depletion | Monitor electrolyte composition and replenish or recover key ions. Systems like the Electrochemical Recovery and Separation System (ERSS) can recover KOH from effluent with a 94% yield [24]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Measurement Imprecision

Objective: To quantify the imprecision of an analytical method under repeatability and intermediate precision conditions.

Materials:

- Stable control sample or standard

- Relevant analytical instrument and reagents

Methodology:

- Repeatability Assessment:

- Prepare a single homogeneous control sample.

- Analyze the sample at least 10 times in a single session, using the same instrument, reagents, and operator.

- Record all results.

- Intermediate Precision Assessment:

- Using the same control sample, analyze it once per day over at least 10 different days.

- Introduce expected variables, such as different reagent lots or different qualified operators, as per your laboratory's routine practice.

- Record all results.

Data Analysis:

- For each set of data (repeatability and intermediate precision), calculate the mean, Standard Deviation (SD), and Coefficient of Variation (CV %).

- The SD is calculated as: ( SD = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N}\sum{i=1}^{N}(xi - \mu)^2} ) where ( \mu ) is the mean of the measurements and N is the number of measurements [23].

- Compare the CV from the repeatability study to the CV from the intermediate precision study. The intermediate precision CV is expected to be larger, and the difference quantifies the impact of the day-to-day variables.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Degradation in an Electrochemical Advanced Oxidation Process

Objective: To monitor the degradation of contaminants and the potential formation of toxic by-products over time.

Materials:

- Synthetic wastewater solution containing target contaminants (e.g., Atrazine, Carbamazepine, Sulfamethoxazole)

- Electrochemical reactor with Boron-Doped Diamond (BDD) anode

- Power supply

- Supporting electrolyte (e.g., Na₂SO₄, NaCl)

- Analytical equipment (e.g., HPLC, GC-MS)

- Phytotoxicity test kits (e.g., Lactuca sativa seeds)

Methodology [25]:

- System Setup: Prepare the electrochemical cell with a Si/BDD anode. Add the synthetic wastewater and supporting electrolyte to the reactor.

- Process Optimization: Determine optimal parameters (e.g., pH, current density, flow rate). A current density of 10-20 mA cm⁻² is often effective for degradation with a BDD anode [25].

- Experimental Run: Apply the predetermined current density. Collect samples from the reactor at regular time intervals (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 60 minutes).

- Analysis:

- Degradation: Analyze samples to determine the concentration of parent contaminants remaining.

- Mineralization: Measure Total Organic Carbon (TOC) to assess conversion of organics to CO₂.

- Toxicity: Conduct phytotoxicity tests on the treated samples to ensure degradation by-products are less toxic than the original contaminants.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimental Context |

|---|---|

| Boron-Doped Diamond (BDD) Anode | A non-active electrode material highly effective for electrochemical oxidation. It generates large quantities of hydroxyl radicals (•OH) that non-selectively oxidize and mineralize organic pollutants [25]. |

| Cation Exchange Membrane (CEM) | Used in electrochemical cells to selectively allow the passage of positive ions (cations like K⁺) while blocking anions and other materials. Critical for processes like electrolyte recovery and product separation [24]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte (e.g., Na₂SO₄, NaCl) | Increases the conductivity of the solution in an electrochemical cell. The choice of electrolyte also influences the oxidation pathway; NaCl leads to the formation of active chlorine species, while Na₂SO₄ promotes sulfate radical formation [25]. |

| Stable Control Sample | A sample with a known and consistent concentration of an analyte. It is essential for daily quality control to monitor the precision and stability of analytical instrumentation over time [23]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Materials | Commercially available materials with known, assigned values used to verify that a measurement procedure is operating within predefined precision and accuracy limits [23]. |

Diagrams and Workflows

Experimental Reproducibility Hierarchy

Electrolyte Recovery & Product Separation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How can I proactively detect accuracy degradation in my predictive models? You can use metrics like the Accuracy Degradation Factor (ADF) and Accuracy Degradation Profile (ADP). These work by sequentially reducing the dataset and evaluating model accuracy over smaller, contiguous subsets. The ADF identifies the first point where these reductions cause a significant performance drop. ADF values closer to 0.0 indicate a model more robust to dataset shifts, while values near 1.0 signal lower robustness and potential future accuracy issues [26].

Our lab's results are precise but not accurate. What is the most likely cause? This pattern typically indicates a significant bias in your measurement system. Under repeatability conditions, where imprecision is minimized, bias becomes most evident. Potential sources include a miscalibrated instrument, an interfering substance in your samples, or an issue with your reference standard. You should investigate instrument calibration and method validation data to identify the systematic error [23].

Why is product separation important in electrochemical degradation studies? Efficient product separation is critical for two main reasons: 1) System Health: It prevents the accumulation of reaction products in the electrolyte, which can poison the electrode catalyst or interfere with the main reaction, leading to performance degradation. 2) Toxicity Assessment: Some degradation by-products can be more toxic than the original contaminant. Separating and analyzing these products, followed by phytotoxicity tests, is essential to ensure the treatment process is effectively reducing environmental hazard [25].

What does "text has enhanced contrast" mean in the context of generating diagrams?

This is a rule from web accessibility (WCAG Level AAA) that requires a high contrast ratio between text and its background to ensure legibility. For diagrams, it means explicitly setting the fontcolor to be distinct from the node's fillcolor. Large-scale text should have a contrast ratio of at least 4.5:1, and other text at least 7:1. This practice ensures your diagrams are readable for all users and when printed in grayscale [27] [28].

Advanced Degradation Mitigation: From Novel Materials to Hybrid Systems

FAQ: Electrode Selection & Performance

Q1: What are the key advantages of Magnéli phase Ti4O7 electrodes over other materials? Magnéli phase Ti4O7 electrodes offer a unique combination of high electrical conductivity (comparable to graphite), exceptional corrosion resistance, and a wide electrochemical potential window [29] [30]. Their high oxygen evolution potential (~2.20 V vs SHE) minimizes side reactions and favors the electrochemical oxidation of persistent pollutants [31]. They are also more cost-effective than boron-doped diamond (BDD) for large-scale applications like water treatment [29].

Q2: When should I choose a Boron-Doped Diamond (BDD) electrode? BDD electrodes are ideal when you require an extremely wide electrochemical window and high reactivity for generating hydroxyl radicals (•OH) [32]. They are highly effective for the complete mineralization of stubborn organic contaminants, such as oxalic acid in nitric acid media, achieving degradation to below 0.001 mol/L [32]. They also exhibit excellent corrosion resistance and low surface adsorption [32].

Q3: What are common issues with graphite electrodes, and how can they be mitigated? Graphite electrodes, while highly conductive, are prone to several issues:

- Oxidation: Exposure to high temperatures and oxygen causes material degradation. This can be mitigated by applying protective coatings and storing electrodes in a dry environment [33].

- Breakage: Mechanical stress and improper handling lead to breakage. Using proper lifting equipment and avoiding dropping or bumping the electrodes is crucial [33].

- Graphite Flaking: Thermal cycling and mechanical wear can cause flaking. Regular inspections for surface cracks and porosity, along with proper furnace condition monitoring, are essential for prevention [33].

Q4: How can I improve the performance and stability of my Ti4O7 electrode? Doping is an effective strategy. Incorporating transition metals (e.g., Ce³⁺, Pd) via methods like sintering or sol-gel can enhance electrocatalytic activity, increase conductivity, and stabilize oxygen vacancies [30] [31]. For instance, Ce³⁺-doped Ti4O7 anodes have shown a 2.4 times increase in the PFOS degradation rate and a 19.6% extension in service life [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Rapid Performance Degradation of Electrode

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Fouling/Passivation | Perform Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to check for surface deposits or cracks. Run Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) in a clean electrolyte to compare with baseline performance [34]. | Clean the electrode surface according to manufacturer guidelines. For Ti4O7, check for oxidation to less conductive phases (e.g., Ti5O9) using Raman spectroscopy [34] [29]. |

| Chemical Oxidation/Corrosion | Inspect for visual damage or erosion. Use Raman spectroscopy to confirm the stability of the material's structure (e.g., diamond peak at 1332 cm⁻¹ for BDD) [34] [33]. | Ensure the electrode potential and current density are within the material's stable window. For graphite, ensure protective coatings are applied and operating temperatures are controlled [33]. |

| Physical Damage | Conduct a visual inspection for cracks, chips, or delamination [33]. | Implement proper handling procedures. Use correct lifting equipment and avoid mechanical stress. Repair minor damages promptly [33]. |

Issue 2: Low Contaminant Degradation Efficiency

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Transfer Limitations | Analyze the system hydrodynamics. In flow-through systems, evaluate the effect of increasing flow rate on degradation rate [35]. | Switch to a porous Reactive Electrochemical Membrane (REM) configuration to enhance mass transfer of pollutants to the electrode surface [35] [36]. |

| Insufficient Anodic Potential | Measure the applied potential versus a reference electrode. Compare it to the known oxygen evolution potential (OEP) of the electrode material [31]. | Increase the cell voltage to ensure the potential is high enough to drive direct electron transfer or generate sufficient •OH radicals, but stay within the electrode's stable window [31]. |

| Non-optimal Electrolyte | Test degradation efficiency at different pH levels and with varying supporting electrolyte concentrations [32]. | Optimize the electrolyte composition and concentration. For example, excessive nitric acid concentration can reduce the electrooxidation rate of oxalic acid on BDD [32]. |

Issue 3: Unstable Cell Voltage or High Resistance

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Degraded Electrical Contacts | Inspect all connectors for corrosion or looseness. Measure the solution resistance via Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) [37]. | Clean and tighten all electrical connections. Ensure connectors are made from corrosion-resistant materials suitable for the electrolyte [33]. |

| Electrode Micro-cracking | Use SEM to examine the electrode surface and coating for micro-cracks or delamination, which can increase resistance [34]. | For coated electrodes like BDD on graphite, verify the integrity of the coating. A post-CV SEM analysis can confirm no cracks or delamination [34]. |

Quantitative Performance Data

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics of Electrode Materials

| Material | Electrical Conductivity | Oxygen Evolution Potential (V vs SHE) | Exchange Current Density (i₀, A/cm²) | Stability in Acidic Media |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnéli Ti4O7 | ~1.6 × 10³ S/cm [30] | ~2.20 V [31] | Varies with doping | High (Half-life of 50 years in 4 M H₂SO₄) [30] |

| BDD | Data not available | >2.00 V (inferred) | 8.34 × 10⁻⁵ [34] | Excellent [34] [32] |

| Graphite | ~1000 S/cm [30] | Data not available | Data not available | Prone to oxidation [33] |

Table 2: Degradation Performance for Select Contaminants

| Electrode | Target Contaminant | Key Operational Parameters | Performance Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ti4O7 (Doped) | PFOS (in water) | Anodic potential: 3.0-3.5 V vs SHE [31] | High degradation efficiency; EE/O in low single digit (kWh/m³) [31] |

| BDD | Oxalic Acid (in HNO₃) | Current Density: 60 mA/cm²; Plate spacing: 2 cm [32] | Concentration reduced to <0.001 mol/L [32] |

| BDD/Graphite Composite | Alkaline Fuel Cell | Electrolyte: 1 M NaOH; 12 hrs CV testing [34] | Stable performance; peak current densities ~35% lower than pure graphite [34] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Evaluating Electrode Stability via Cyclic Voltammetry

This method assesses the electrochemical stability and corrosion resistance of an electrode material in a specific electrolyte [34].

- Setup: Use a standard three-electrode cell with the test electrode as the working electrode, a Pt wire/mesh as the counter electrode, and a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) or Ag/AgCl as the reference.

- Electrolyte: Prepare 1 M NaOH solution (or another electrolyte relevant to your application).

- Procedure: Run cyclic voltammetry scans between a predetermined potential window (e.g., -0.5 V to +0.8 V vs SCE) for multiple cycles (e.g., 12 hours).

- Analysis: Overlap the CV traces from the beginning and end of the test. A complete overlap indicates high stability. Post-test, use SEM to check for physical damage and Raman spectroscopy to confirm chemical structure integrity [34].

Protocol 2: Electrochemical Oxidation of Organic Pollutants using Ti4O7

This protocol outlines the steps for degrading persistent organic pollutants like PFAS using a Ti4O7 anode [35] [31].

- Reactor Configuration: Set up an electrochemical cell, preferably with a REM in flow-through mode to overcome mass transfer limitations [35].

- Electrolyte and Contaminant: Spike the water matrix (e.g., simulated wastewater) with the target pollutant (e.g., PFOS at μg/L-mg/L levels). Add a supporting electrolyte like 0.1 M KOH if necessary.

- Operational Parameters: Apply a constant current or potential. For PFOS degradation, anodic potentials of 3.0-3.5 V vs SHE are effective [31].

- Monitoring: Take samples at regular intervals. Analyze contaminant concentration using techniques like LC-MS/MS. Monitor fluoride ion release to track mineralization.

- Efficiency Calculation: Calculate the Electrical Energy per Order (EE/O) to quantify and compare energy efficiency.

Core Mechanisms & Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Electrode Fabrication and Testing

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| TiO₂ Powder | Primary precursor for synthesizing Magnéli phase TinO2n-1 via thermal reduction [29] [30]. | Synthesis of Ti4O7 electrodes and REMs. |

| Boron Source | Dopant for creating p-type semiconductor diamond thin films. | Fabrication of Boron-Doped Diamond (BDD) electrodes [34]. |

| Cerium(III) Chloride (CeCl₃) | Dopant precursor for enhancing the electrocatalytic activity of Ti4O7. | Preparation of Ce³⁺-doped Ti4O7 anodes via sol-gel/sintering to improve PFOS degradation rates [31]. |

| 5,5-Dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DMPO) | Spin trap for Electron Spin Resonance (ESR) spectroscopy. | Detection and semi-quantification of short-lived hydroxyl radicals (•OH) during electrochemical oxidation [32]. |

| Nafion Membrane | Cation exchange membrane. | Used in electrolytic cells to separate anolyte and catholyte compartments, preventing interference [32] [24]. |

| Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) | Common alkaline electrolyte. | Used in CO2 reduction reactions and as an electrolyte in various electrochemical cells [24]. |

Electrochemical Oxidation (EO) for Destructive Treatment of PFAS

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: What are the primary mechanisms for PFAS destruction in Electrochemical Oxidation?

PFAS destruction in EO systems occurs through two main mechanisms operating at the anode surface. Direct Electron Transfer (DET) involves direct electron withdrawal from PFAS molecules adsorbed on the anode surface, initiating decarboxylation or desulfonation. Simultaneously, indirect oxidation occurs via powerful oxidants, primarily hydroxyl radicals (·OH), generated in situ from water oxidation. These radicals mediate secondary reactions that decompose PFAS into shorter-chain intermediates and ultimately mineralize them to CO₂, F⁻, and H₂O [35] [20] [38]. The successive breakdown of long-chain PFAS into short-chain compounds is a key indicator that these mechanisms are functioning correctly [38].

FAQ 2: Why is my EO system inefficient at degrading short-chain PFAS?

The recalcitrance of short-chain PFAS (e.g., C1-C4) is a common challenge. This is often due to mass transfer limitations and their lower adsorption energy on the electrode surface compared to long-chain PFAS. Short-chain PFAS are more hydrophilic, making it harder for them to reach the anode surface where destructive reactions occur. To improve efficiency, consider:

- Optimizing mass transfer: Using porous electrodes in a flow-through configuration, such as a Reactive Electrochemical Membrane (REM), can enhance the transport of PFAS to the electrode surface [35].

- Electrode material selection: High-oxygen-overpotential anodes like Boron-Doped Diamond (BDD) are more effective at generating the conditions needed to destroy stubborn short-chain compounds [39] [40].

FAQ 3: My electrodes are fouling rapidly, leading to increased energy demand. What could be the cause?

Electrode fouling is a major operational hurdle, often caused by the precipitation of inorganic salts (e.g., calcium carbonate) or the accumulation of organic matter on the electrode surface. This foulant layer increases system resistance and overpotential, reducing efficiency [41]. Mitigation strategies include:

- Pre-treatment: Remove scaling ions and a portion of the organic load from the feedwater before EO treatment.

- Operational adjustments: Implementing periodic current reversal or acid rinse cycles can help desorb foulants and restore electrode activity [41].

- Material choice: Selecting electrode materials that are less prone to fouling for specific water matrices can extend service life.

FAQ 4: What is a key indicator of successful PFAS mineralization, beyond the disappearance of the parent compound?

The definitive quantitative indicator of PFAS destruction is defluorination, measured by the release of fluoride ions (F⁻) into solution. The theoretical maximum fluoride release can be calculated based on the initial PFAS concentration. The measured F⁻ concentration as a percentage of this theoretical maximum provides the defluorination ratio, a critical metric for assessing mineralization efficiency [40]. Additionally, a decrease in Extractable Organofluorine (EOF) shows that the total amount of fluorinated organic compounds is reducing [42].

Quantitative Performance Data

The following table summarizes key performance metrics for electrochemical oxidation of PFAS from recent studies, providing benchmarks for researchers.

Table 1: Performance Metrics for Electrochemical Oxidation of PFAS

| PFAS Compound | Scale / Context | Anode Material | Removal Efficiency | Key Metric (e.g., Defluorination) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFOA & PFOS | Pilot-scale (189 L) | Boron-Doped Diamond (BDD) | PFOS: >99.9% (to non-detect)PFOA: 98.6% | ~60% defluorination of PFOA | [40] |

| Mixed PFAS (26+ mg/L) | Industrial Wastewater | Mixed Electrode Materials | >98.8% of all PFAS | Successive breakdown of long- to short-chain PFAS demonstrated | [38] |

| Mixed PFAS in Foamate | Pilot-scale (Treatment Train) | Information Not Specified | Total PFAS: ~50%Long-chain: up to 86%Short-chain: up to 31% | Extractable Organofluorine reduced by up to 44% | [42] |

| General PFAS | Literature Review | BDD, Ti₄O₇, etc. | >99% for long-chain | Efficiency depends on anode, current density, and matrix | [20] |

Standard Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Batch-mode Electrochemical Oxidation of PFAS with Defluorination Analysis

Objective: To evaluate the degradation and mineralization efficiency of a specific anode material for a target PFAS compound in a controlled, aqueous solution.

Materials:

- Electrochemical Reactor: A single-compartment cell (e.g., 250 mL beaker).

- Electrodes: Anode (Test material, e.g., BDD, Ti₄O₇); Cathode (inert material, e.g., Pt or stainless steel); Reference Electrode (optional, for controlled potential experiments).

- Power Supply: DC power source for galvanostatic (constant current) operation.

- Analytical Instruments: LC-MS/MS for PFAS analysis; Ion Chromatograph (IC) for fluoride ion analysis.

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a solution of the target PFAS (e.g., 10 mg/L PFOA) in a background electrolyte (e.g., 50 mM Na₂SO₄). Adjust the initial pH if necessary.

- Baseline Sampling: Before applying current, take a time-zero (t=0) sample for PFAS and fluoride analysis.

- Operation: Immerse the electrodes in the solution and apply a constant current density (e.g., 10-50 mA/cm²). Maintain constant stirring to ensure mixing.

- Time-course Sampling: At predetermined time intervals (e.g., 15, 30, 60, 120 min), withdraw aliquots from the reactor.

- Sample Processing: Filter each sample (0.22 μm syringe filter) to remove any particulates.

- Analyze one portion directly via LC-MS/MS to quantify the concentration of the parent PFAS and any intermediate products.

- Analyze another portion via IC to quantify the fluoride ion concentration released.

- Data Analysis: Calculate PFAS removal efficiency and defluorination ratio over time.

Protocol: Pilot-Scale Treatment of PFAS in Complex Matrices

Objective: To assess the long-term performance and durability of an EO system for treating real-world, complex water streams like landfill leachate or reverse osmosis concentrate.

Materials:

- Pilot-scale EO Unit: A flow-through reactor with multiple BDD or other specialized electrodes [40] [41].

- Feed Tank: For the contaminated water (e.g., membrane concentrate, raw leachate).

- Pumping System: To deliver a continuous flow of water through the reactor.

- Monitoring System: For parameters like flow rate, pH, conductivity, and power consumption.

Procedure:

- System Setup: Connect the EO unit to the feed source. Establish a continuous flow rate based on the reactor's hydraulic retention time.

- Baseline Characterization: Perform a comprehensive analysis of the influent, including target PFAS, EOF, general water quality parameters, and fluoride.

- Long-term Operation: Operate the system continuously for an extended period (e.g., 30-60 days) to monitor electrode longevity and fouling potential [41].

- Process Monitoring & Maintenance:

- Monitor system voltage and current to track changes in electrode performance.

- Perform periodic (e.g., daily or weekly) PFAS and fluoride analysis on the effluent.

- Implement automated cleaning cycles (e.g., acid rinses or current reversal) as needed to mitigate fouling [41].

- Data Analysis: Evaluate removal efficiency over time, energy consumption per volume treated (kWh/m³), and the frequency of maintenance required for stable operation.

Process Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the key degradation pathways for PFOA and PFOS during electrochemical oxidation, integrating direct and indirect mechanisms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for EO-PFAS Research

| Item | Function / Explanation | Research Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Boron-Doped Diamond (BDD) Anode | A highly effective anode material due to its wide potential window, high stability, and strong ability to generate hydroxyl radicals [20] [40]. | The benchmark material for destructive EO; high cost but offers superior performance for difficult-to-oxidize short-chain PFAS. |

| Magnéli Phase Titanium Suboxide (Ti₄O₇) Anode | A ceramic electrode known for high electrical conductivity and stability. Effective for PFAS destruction via direct electron transfer and radical generation [35]. | A promising, cost-effective alternative to BDD. Often used in Reactive Electrochemical Membranes (REMs) to overcome mass transfer limits [35]. |

| Sodium Sulfate (Na₂SO₄) Electrolyte | An inert supporting electrolyte used to increase the conductivity of the test solution without introducing competitive oxidants [40]. | Concentration (e.g., 50 mM) must be optimized. Avoid electrolytes with chloride, which can form less reactive chlorinated species. |

| ¹⁴C-labeled PFOA/PFOS | Radiolabeled PFAS compounds used as tracers to accurately track mineralization pathways and quantify the formation of ¹⁴CO₂ as a final product [40]. | Provides definitive proof of complete mineralization but requires specialized safety protocols and scintillation counting equipment. |

| PFAS-specific Anion Exchange Resin | Used for solid-phase extraction (SPE) to pre-concentrate PFAS from large volume samples before analysis, enabling detection at very low (ppt) concentrations [43]. | Critical for analyzing real environmental samples where PFAS concentrations are near regulatory limits. |

| Competitive Background Organics | Model natural organic matter (e.g., humic or fulvic acids) used to simulate complex water matrices and study their inhibitory effect on PFAS degradation kinetics [20]. | Essential for translating lab-scale results to real-world applications, as NOM competes for oxidizing species. |

Bioelectrochemical Systems (BES) and Microbial Biotransformation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental principle behind Bioelectrochemical Systems (BES)? BES are devices that integrate microorganisms with electrochemistry to catalyze redox reactions. In these systems, electroactive microorganisms (exoelectrogens) catalyze the oxidation of organic matter at the anode, releasing electrons and protons. The electrons travel through an external circuit to the cathode, generating an electrical current or driving the synthesis of valuable chemicals, while protons migrate through an electrolyte to maintain charge balance [44] [45] [46].

2. What are the primary mechanisms for electron transfer from microbes to electrodes? There are two primary mechanisms:

- Direct Electron Transfer (DET): Requires physical contact between the microbial cell membrane and the electrode. Electrons are transferred via membrane-bound redox proteins, such as cytochromes, or through conductive microbial appendages known as bacterial nanowires [44] [47].

- Mediated Electron Transfer (MET): Relies on soluble redox mediators that shuttle electrons from the microbial cells to the electrode. These mediators can be naturally produced by the microbes themselves (e.g., phenazines by Pseudomonas aeruginosa) or artificially added to the system (e.g., neutral red, anthraquinone-2,6-disulfonate) [44] [45].

3. Our BES is producing significantly lower power density than expected. What could be the cause? Low power density is a common challenge often attributed to several factors [47] [45]:

- High Internal Resistance: This can be caused by poor ionic conductivity of the electrolyte, large distance between electrodes, or fouling of the cation exchange membrane.

- Inefficient Electron Transfer: This may be due to a non-optimal microbial community, lack of essential redox mediators, or unsuitable electrode materials that hinder biofilm formation.

- Mass Transfer Limitations: Inadequate mixing can lead to substrate depletion at the anode or proton accumulation, creating localized acidic conditions that inhibit microbial activity.

4. How can we mitigate cathode biofouling in our systems? Cathode biofouling, the undesirable formation of biofilm that blocks reaction sites, can be mitigated by using air-cathodes which limit microbial growth, applying periodic polarity reversal, or using anti-fouling coatings on the cathode surface [45].

5. What are the key performance metrics for evaluating a BES? The key performance parameters are summarized in the table below [47]:

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for BES

| Parameter | Description | Typical Units |

|---|---|---|

| Current Density | The electrical current flowing per unit area of the electrode (typically anode). | A m⁻² |

| Power Density | The electrical power generated per unit area or volume of the reactor. | W m⁻² or W m⁻³ |

| Coulombic Efficiency (CE) | The fraction of electrons recovered as current from the total electrons available in the substrate. | % |

| Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) Removal | A measure of the system's efficacy in treating wastewater by quantifying organic pollutant removal. | % |

6. Can BES be applied beyond energy generation? Yes, BES have diverse applications [48] [45] [49]:

- Microbial Electrolysis Cells (MECs): Produce hydrogen, methane, or other valuable chemicals (e.g., acetate) by applying a small external voltage.

- Bioremediation: Degrade recalcitrant organic pollutants, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and recover heavy metals from contaminated water and soil.