Mastering Local Heat Transfer Coefficient Simulation: A Comprehensive CFD Guide for Pharmaceutical Research

This comprehensive guide explores Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) modeling of local heat transfer coefficients, a critical parameter in pharmaceutical development.

Mastering Local Heat Transfer Coefficient Simulation: A Comprehensive CFD Guide for Pharmaceutical Research

Abstract

This comprehensive guide explores Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) modeling of local heat transfer coefficients, a critical parameter in pharmaceutical development. We cover foundational principles of convective heat transfer mechanisms in biological systems, detailed methodologies for setting up and solving CFD models, advanced techniques for troubleshooting and optimizing simulations, and rigorous validation approaches against experimental data. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, this article provides practical insights for applying CFD to optimize bioreactor design, sterilization processes, cryopreservation, and targeted drug delivery systems, bridging computational analysis with real-world biomedical applications.

Understanding Local Heat Transfer Coefficients: The Bedrock of Bioprocess CFD Analysis

Theoretical Foundation

The local heat transfer coefficient (h) is a critical parameter quantifying the convective heat transfer rate per unit area and per unit temperature difference between a surface and the adjacent fluid. It is fundamentally defined by Newton's Law of Cooling in its differential form:

[ q'' = -k \frac{\partial T}{\partial y}\bigg|{y=0} = h(Ts - T_\infty) ]

where:

- ( q'' ) = Local heat flux (W/m²)

- ( k ) = Thermal conductivity of the fluid (W/m·K)

- ( T ) = Temperature (K)

- ( T_s ) = Local surface temperature (K)

- ( T_\infty ) = Local free-stream fluid temperature (K)

- ( h ) = Local heat transfer coefficient (W/m²·K)

In biomedical contexts, this concept is pivotal for modeling thermal interactions between medical devices (stents, catheters), biological tissues, and blood flow, influencing outcomes from hyperthermia treatment to drug delivery system design.

Table 1: Typical Ranges of Local Heat Transfer Coefficient (h) in Biomedical Contexts

| Context / Application | Approximate h Range (W/m²·K) | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Large Arteries (e.g., Aorta) | 300 - 1,200 | Pulsatile flow, vessel diameter, blood rheology |

| Microvasculature (Capillaries) | 1,000 - 5,000 | Low velocity, small diameter, near-stagnant flow |

| Tissue Surface (Skin to Air) | 2 - 25 (Natural Conv.) | Ambient air flow, surface geometry, temperature gradient |

| Catheter Surface in Blood | 150 - 800 | Catheter size, blood velocity, placement location |

| Tumor during Thermal Ablation | 50 - 400 (modeled) | Perfusion rate, tissue properties, probe geometry |

Key Experimental Protocols for Determining Localh

Protocol 2.1: In-Vitro Measurement Using Heated Thin-Foil Technique

This protocol details a common method for obtaining spatially resolved h distributions on physical models.

Materials & Apparatus:

- Test Model: A geometrically accurate phantom (e.g., of a blood vessel or stent) manufactured from a low thermal conductivity substrate.

- Heating Element: A thin, electrically conductive foil (e.g., constantan, 25µm thickness) adhered to the model surface.

- DC Power Supply: To provide a constant, uniform Joule heating flux through the foil.

- Infrared (IR) Thermography System: High-resolution, calibrated IR camera to measure the outer surface temperature distribution (T_s).

- Flow System: A precisely controlled circulatory loop with a blood-mimicking fluid at controlled temperature (T_∞).

- Data Acquisition System: Synchronized with the IR camera and flow sensors.

Procedure:

- Setup: Mount the foil-covered model in the test section. Fill the flow loop with working fluid and set to the target bulk temperature (T_∞). Ensure no ambient air movement.

- Calibration: Calibrate the IR camera using surface thermocouples. Record the emissivity of the foil coating.

- Baseline Acquisition: With zero heating power, record the initial surface temperature (should equilibrate to T_∞).

- Heated Experiment: Apply a known, constant voltage (V) to the foil, generating a uniform heat flux ( q'' = V^2/(R*A) ), where R is foil resistance and A is surface area. Allow the system to reach steady state (~15-30 mins).

- Data Recording: Simultaneously capture the IR surface temperature map (Ts) and log the bulk fluid temperature (T∞).

- Calculation: Compute the local h at each pixel/point using Newton's Law: ( h = q'' / (Ts - T∞) ). Spatially average or map the results.

Protocol 2.2: Computational (CFD) Protocol for LocalhEstimation

This protocol outlines the standard workflow for determining h using Computational Fluid Dynamics, which is central to the broader thesis.

Procedure:

- Geometry & Meshing: Create a 3D CAD model of the domain (e.g., artery with stent). Generate a high-quality computational mesh with refined boundary layers at all fluid-solid interfaces.

- Physics Definition:

- Solver: Steady-state or transient pressure-based solver.

- Model: Enable energy equation. Select appropriate viscous model (e.g., k-ω SST for transitional flows).

- Boundary Conditions: Set inlet velocity/pressure and temperature. Set wall boundaries as no-slip. Define a constant wall heat flux (CWHF) or constant wall temperature (CWT) condition.

- Material Properties: Define density, viscosity, specific heat, and thermal conductivity for fluid (blood analog) and solid.

- Solution: Run simulation until residuals converge (typically < 10^-6 for energy). Monitor surface parameters for stability.

- Post-Processing:

- Extract the local wall temperature (T_s) and the local heat flux (q'') from the solved field.

- Compute the local h field using the defining equation.

- Validate results by comparing spatially averaged h with empirical correlations (e.g., Dittus-Boelter for tube flow).

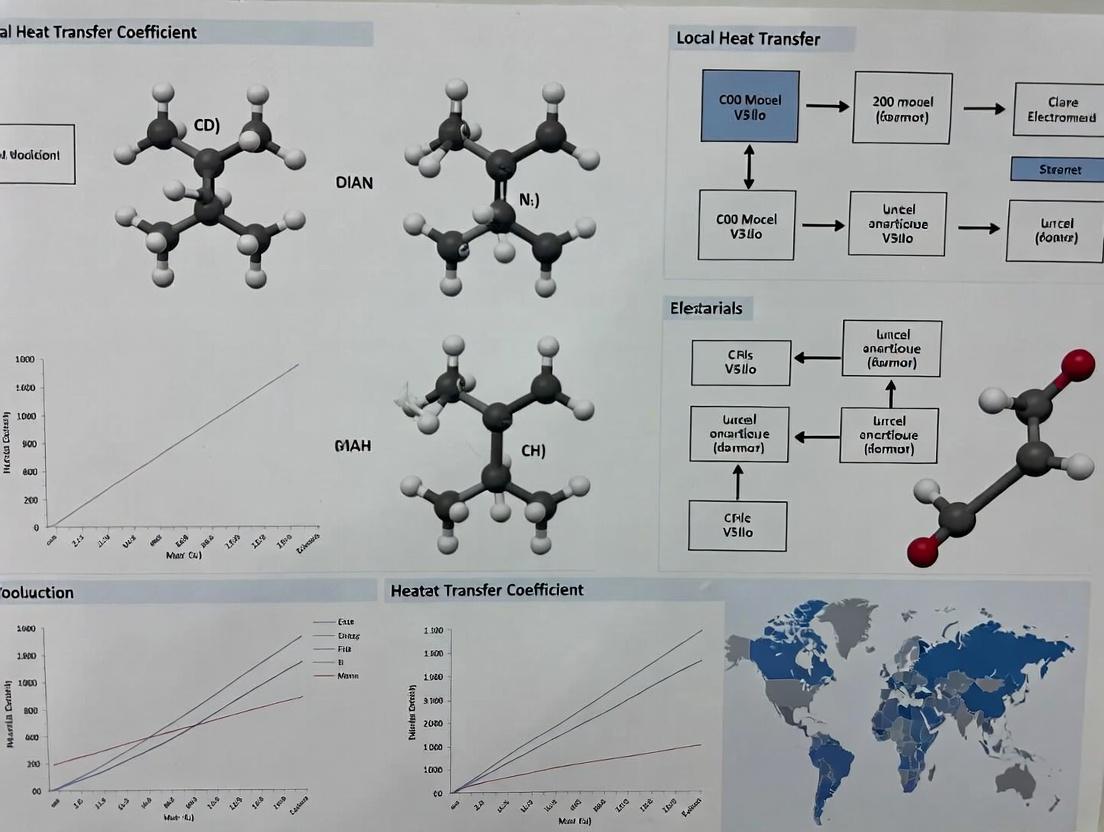

Diagram Title: CFD Protocol for Local h Estimation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Experimental Determination of Local h

| Item | Function in Experiment | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Blood-Mimicking Fluid | Provides physiologically relevant viscosity and thermal properties for in-vitro modeling. | Aqueous Glycerol (60-40%) or specialized particle suspensions (e.g., for PIV). |

| Thin-Foil Heater | Generates a uniform, measurable heat flux at the model surface for inverse calculation of h. | Constantan foil, 25-50 µm thick, laminated with insulating layer. |

| Infrared Thermography Camera | Measures high-resolution, non-contact 2D temperature maps on the heated surface. | MWIR or LWIR camera, <50 mK thermal sensitivity, calibrated for target emissivity. |

| Temperature-Controlled Flow Loop | Maintains a precise and stable bulk fluid temperature (T_∞) for the experiment. | Recirculating bath with ±0.1°C stability, heat exchanger in reservoir. |

| Digital Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) System | Measures instantaneous velocity fields to correlate flow structures with local h maps. | Double-pulse Nd:YAG laser, high-speed CMOS camera, seeding particles (e.g., 10 µm silver-coated glass). |

| Anemometry Probe (Hot-wire or Hot-film) | Provides point measurements of local fluid velocity for boundary condition specification or validation. | Miniature hot-film probe, suitable for liquid flow, frequency response >1 kHz. |

Application in Biomedical Research: Linking h to Biological Response

Local heat transfer directly influences therapeutic efficacy and safety. For instance, in drug-coated stent (DES) deployment, local h affects drug elution kinetics and arterial wall temperature.

Diagram Title: Linking Local h to Stent Bio-Response

Table 3: Impact of Local h Variation on Biomedical Processes

| Process | High Local h Implication | Low Local h Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Hyperthermia Cancer Treatment | Efficient heat removal from applicator; may require higher power to reach target tissue temperature. | Risk of localized overheating, causing unintended tissue necrosis near the device. |

| Hypothermia Induction (Therapeutic Cooling) | Enhanced core cooling rate via heat exchange catheters. | Inefficient cooling, longer time to reach target temperature, reduced therapeutic benefit. |

| Drug Release from Thermally-Sensitive Hydrogels | Rapid thermal equilibration; precise, external temperature-control of release profile. | Significant lag between applied external temperature and gel temperature, leading to imprecise drug dosing. |

Application Notes

In Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) modeling of pharmaceutical processes, a uniform or average heat transfer coefficient (HTC) is insufficient for predicting real-world performance. This application note highlights the critical impact of spatial variation in both equipment (e.g., freeze-dryers, bioreactors) and biological tissues (e.g., tumors, organoids) on process efficacy, product quality, and therapeutic outcomes.

1. Spatial Variation in Pharmaceutical Equipment: In lyophilization, the local HTC at the vial position within the freeze-dryer shelf determines the primary drying rate and final product homogeneity. Edge vials experience significantly higher radiative heat transfer than center vials, leading to faster drying and potential over-drying if not accounted for. In bioreactors, local variations in shear stress and nutrient concentration, driven by impeller design and sparger location, directly affect cell growth, viability, and protein expression.

2. Spatial Variation in Biological Tissues: Tumors exhibit pronounced heterogeneity in vascular density, perfusion, and stromal composition. This creates spatially variable heat and mass transfer environments during hyperthermia-based treatments or drug delivery. Assuming uniform tissue properties leads to inaccurate predictions of thermal dose and drug penetration, compromising treatment planning.

3. Integration via Multiscale CFD Modeling: Advanced CFD models that incorporate locally resolved HTCs and tissue properties enable the optimization of process parameters (e.g., shelf temperature ramps in lyophilization) and therapeutic protocols (e.g., laser power modulation in photothermal therapy). This approach moves beyond "one-size-fits-all" averages to achieve precise, predictable, and personalized outcomes.

Table 1: Measured Local Heat Transfer Coefficients (HTC) in a Laboratory Freeze-Dryer

| Vial Position on Shelf | HTC Range (W/m²·K) | Primary Heat Transfer Mechanism | Impact on Primary Drying Time (vs. Center Vial) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Center Vial | 10 - 15 | Conduction | Baseline (0% change) |

| Edge Vial (Front) | 18 - 25 | Conduction & Radiation | 25-35% Reduction |

| Corner Vial | 22 - 30 | Conduction & Radiation | 35-45% Reduction |

Table 2: Spatial Variation in Tumor Tissue Properties Affecting Heat/Mass Transfer

| Tissue Property | Measured Range in Solid Tumors | Key Driver of Variation | Impact on Hyperthermia Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perfusion Rate | 0.5 - 5.0 mL/min/100g | Vascular Density & Maturity | Local temperature variation up to 5-7°C |

| Thermal Conductivity | 0.45 - 0.55 W/m·K | Water Content, Necrosis | Altered heat dissipation and thermal lesion size |

| Interstitial Pressure | 5 - 40 mmHg | Lymphatic Dysfunction, Stroma | Reduced convective drug delivery to core |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Mapping Local Heat Transfer Coefficients in a Freeze-Dryer

Objective: To empirically determine the spatial distribution of HTCs across a freeze-dryer shelf.

Materials: Laboratory-scale freeze-dryer, array of product vials (e.g., 10x10), thermocouples, data logger, manometer, pure water.

Procedure:

1. Setup: Fill all vials with a known volume of pure water. Install calibrated thermocouples in vials at strategic positions (center, edge, corner).

2. Freezing: Load vials onto the pre-cooled shelf (-40°C). Freeze completely.

3. Primary Drying: Initiate primary drying at a constant shelf temperature (e.g., 0°C) and chamber pressure (e.g., 0.1 mBar). Record vial bottom temperatures (Tb) and shelf temperature (Ts) every minute.

4. Data Analysis: Using the manometric temperature measurement (MTM) method or a gravimetric method, determine the sublimation front temperature (Ti). Calculate the local HTC for each instrumented vial position using the heat balance equation: HTC = (Q_sub) / (A * (Ts - Tb)), where Q_sub is the sublimation rate (from gravimetric data) and A is the cross-sectional area of the vial.

5. Mapping: Interpolate results to create a 2D contour map of HTC distribution across the shelf.

Protocol 2: Characterizing Spatial Perfusion in Ex Vivo Tumor Models

Objective: To quantify local variation in blood perfusion within a tumor using laser speckle contrast imaging (LSCI).

Materials: Animal tumor model (e.g., murine subcutaneous xenograft), laser speckle contrast imaging system, isoflurane anesthesia setup, physiological monitor, image analysis software.

Procedure:

1. Preparation: Anesthetize the animal and surgically expose the tumor of interest, ensuring minimal disturbance to vasculature.

2. Imaging: Position the LSCI camera perpendicular to the tumor surface. Acquire baseline speckle images under stable physiological conditions (monitor heart rate, temperature).

3. Data Acquisition: Record a time series of speckle contrast images (typically >100 frames). Maintain constant ambient lighting and camera settings.

4. Processing: Compute speckle contrast (K) for each pixel: K = σ / <I>, where σ is the standard deviation and is the mean pixel intensity in a small region.

5. Calculation: Convert speckle contrast maps to relative blood flow velocity maps using the relation: Perfusion ∝ 1 / K². Calibrate with a known standard if absolute flow is required.

6. Analysis: Segment the tumor image into core, intermediate, and peripheral regions. Calculate average perfusion values for each region and generate a spatial heterogeneity index (e.g., coefficient of variation across the tumor area).

Visualizations

Title: Protocol for Mapping Freeze-Dryer Local HTC

Title: LSCI Workflow for Tumor Perfusion Mapping

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Spatial Variation Studies in Pharma & Biologics

| Item/Category | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Micro-PIV (Particle Image Velocimetry) System | Measures local fluid velocity fields at micron-scale in bioreactors or microfluidic tissue models. |

| Fluorescent Nanothermometers (e.g., polymer dots) | Enables spatially resolved temperature mapping within biological tissues during hyperthermia studies. |

| Manometric Temperature Measurement (MTM) Software | Critical for non-invasively determining sublimation interface temperature in freeze-drying HTC studies. |

| Laser Speckle Contrast Imaging (LSCI) System | Provides full-field, real-time maps of relative blood perfusion in exposed tissues and tumors. |

| Tissue-Mimicking Phantoms (with controlled heterogeneity) | Calibrates imaging systems and validates CFD models of heat and mass transfer in complex geometries. |

| Wireless Micro-Thermocouples (e.g., 100μm beads) | Allows precise, localized temperature monitoring within product vials or tissue without disturbing the field. |

| Computational Mesh Generation Software (e.g., ANSYS Meshing) | Creates high-fidelity, locally refined meshes essential for resolving spatial gradients in CFD simulations. |

Within Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) modeling research focused on determining local heat transfer coefficients in biological systems, understanding the interplay of fundamental heat transfer mechanisms in complex fluids is paramount. These coefficients are critical inputs for predictive models used in drug delivery system design, thermal ablation therapy planning, and hyperthermia treatment optimization. Biological fluids—such as blood, synovial fluid, mucus, and heterogeneous tumor interstitial fluid—exhibit non-Newtonian behavior, complex rheology, and variable optical properties, which dramatically alter the relative contributions and effective rates of convection, conduction, and radiation. This document provides application notes and detailed experimental protocols for measuring and quantifying these mechanisms, directly feeding into the development and validation of high-fidelity CFD models.

Table 1: Measured Thermal Properties of Key Biological Fluids

| Fluid Type | Dynamic Viscosity (mPa·s) | Thermal Conductivity (W/m·K) | Specific Heat Capacity (J/kg·K) | Absorption Coefficient (Near-IR) (1/cm) | Scattering Coefficient (1/cm) | Key References (2022-2024) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Blood (Human, 37°C, Hct 45%) | 3.5 - 4.5 (shear-dependent) | 0.49 - 0.52 | 3617 - 3800 | 0.5 - 2.0 | 20 - 50 | Gnyawali et al., 2023; Bioheat Trans. Rep. |

| Blood Plasma (Human, 37°C) | 1.2 - 1.5 | 0.57 - 0.60 | 3900 - 4100 | ~0.1 | < 1 | J. Biomed. Opt., 2022 |

| Tumor Interstitial Fluid (Model) | 1.5 - 8.0 (variable) | 0.48 - 0.55 | 3500 - 4000 | 0.3 - 1.5 (varies with vasculature) | 10 - 30 | Theranostics, 2023 |

| Synovial Fluid (Healthy) | 5 - 50 (shear-thinning) | 0.45 - 0.48 | 3700 - 3900 | Low | Low | Ann. Biomed. Eng., 2024 |

| Mucus (Simulated Lung) | 100 - 5000 (viscoelastic) | ~0.50 | ~4000 | Varies with hydration | Varies with hydration | Eur. J. Pharm. Sci., 2023 |

Table 2: Dominant Heat Transfer Mechanism by Scenario (Qualitative Guide for CFD Input)

| Biological Scenario / Location | Predominant Mechanism(s) | Rationale for CFD Model Prioritization |

|---|---|---|

| Large Artery (e.g., Aorta) | Forced Convection | High-velocity pulsatile flow dominates; conduction in fluid is negligible relative to bulk motion. |

| Capillary Bed / Tissue Periphery | Conduction (with perfusion sink/source) | Low velocity (low Péclet number); heat transfer governed by conduction between fluid and tissue, modeled as a porous medium. |

| Superficial Tissue with Laser Irradiation | Radiation (followed by Conduction/Convection) | Photon penetration and absorption (radiation) is the primary energy input; subsequent redistribution is via conduction and perfusion. |

| Static Fluid Pockets (e.g., Bursa) | Conduction (Natural Convection possible) | No forced flow; heat transfer is primarily conductive, though natural convection may occur with significant temperature gradients. |

| Dense, Viscoelastic Mucus Layer | Conduction | Extremely low Reynolds number flow; convective mixing is minimal. |

Experimental Protocols for Parameter Quantification

Protocol 3.1: Measuring Effective Thermal Conductivity & Conduction in Non-Newtonian Biological Fluids

Objective: To determine the temperature-dependent thermal conductivity (k) of a complex biological fluid under controlled shear conditions, for input into CFD conduction models.

Materials (Research Reagent Solutions):

- Transient Hot-Wire (THW) Cell with nanoscale sensor: Minimizes convection artifacts during measurement.

- Rheometer-coupled Thermal Stage: Allows precise control of fluid shear rate during measurement.

- Test Fluid: e.g., 2% (w/v) Hyaluronic Acid in PBS (simulating synovial fluid), alginate-based tumor interstitial fluid simulant.

- Temperature Controller: Peltier-based, range 20-50°C, ±0.1°C.

- Data Acquisition System: High-frequency (>100 Hz) for capturing transient temperature rise.

Detailed Methodology:

- Setup: Mount the THW sensor in the measurement cell. Connect to the current source and voltage/ temperature monitoring system.

- Calibration: Perform measurements with standard fluids of known thermal conductivity (e.g., distilled water, glycerol) at multiple temperatures.

- Shear Conditioning: Load the test biological fluid into the rheometer-coupled cell. Pre-shear the fluid at a defined shear rate (e.g., 1 s⁻¹, 100 s⁻¹) for 300 seconds to ensure a reproducible rheological state.

- Measurement: Maintain the constant shear. Apply a step-function current to the hot-wire. Record the temperature rise of the wire as a function of time (typically 0.1-1 second).

- Analysis: Fit the recorded temperature-time data to the theoretical model for a line heat source. The slope of the linear region of ΔT vs. ln(t) plot is used to calculate k. [ k = \frac{q}{4\pi \cdot slope} ] where q is the heat input per unit length.

- Repeat: Perform steps 3-5 across a matrix of temperatures (25, 30, 37, 40, 45°C) and shear rates (0.1, 1, 10, 100 s⁻¹). Perform in triplicate.

Protocol 3.2: Quantifying Forced Convective Heat Transfer in a Microfluidic Vasculature Model

Objective: To experimentally determine the local convective heat transfer coefficient (h) for a biological fluid flowing in a microscale channel mimicking a blood vessel.

Materials (Research Reagent Solutions):

- PDMS Microfluidic Device: Fabricated with soft lithography, containing straight or branched channels (diameters 50-200 µm).

- Precision Syringe Pump: For generating steady or pulsatile flow.

- Temperature-controlled Platform: With integrated, localized micro-heater (e.g., thin-film gold resistor) on the channel surface.

- High-Speed Infrared Thermography Camera or Fluorescent Thermometry Setup: (e.g., using Rhodamine B).

- Test Fluid: Blood-mimicking fluid (e.g., 40% glycerin in water with 1% Xanthan gum for shear-thinning) or treated whole blood (with anticoagulant).

Detailed Methodology:

- Instrumentation: Mount the microfluidic device on the temperature stage. Connect the syringe pump. Calibrate the IR camera/fluorescence intensity against known temperatures using the device itself.

- Flow Establishment: Set the stage to a uniform baseline temperature (e.g., 37°C). Initiate fluid flow at a target wall shear rate (calculate from flow rate and channel geometry).

- Heat Application: Activate the integrated micro-heater at a known, constant power (P).

- Data Collection: Record the steady-state temperature distribution, specifically measuring the heater surface temperature (Ts) and the bulk fluid temperature upstream (Tb) using IR/fluorescence.

- Calculation: The local convective heat transfer coefficient is calculated using Newton's law of cooling: [ q'' = h (Ts - Tb) ] where q'' is the heat flux (P/heater area). Therefore, [ h = \frac{P/A}{(Ts - Tb)} ].

- Parametric Study: Repeat for a range of flow rates (Reynolds numbers: 0.01 - 100) and fluid types. Correlate results as Nusselt number (Nu = hD/k) vs. Reynolds (Re) and Prandtl (Pr) numbers to generate correlations for CFD models.

Protocol 3.3: Determining Radiative Absorption and Scattering Coefficients

Objective: To measure the optical properties (absorption coefficient μa, scattering coefficient μs, anisotropy factor g) of a biological fluid for radiative heat transfer modeling (e.g., in laser therapy).

Materials (Research Reagent Solutions):

- Integrating Sphere Spectrophotometer: Equipped for 600-1100 nm range (common therapeutic window).

- Cuvettes: With precise, small path lengths (0.5 mm, 1 mm, 2 mm).

- Light Source: Tunable laser or broadband source with monochromator.

- Reference Fluids: Intralipid (scattering standard), India Ink (absorption standard).

- Test Fluid: Hemolyzed blood (uniform absorption), whole blood, or nanoparticle-laden fluid.

Detailed Methodology:

- System Calibration: Perform baseline scans with empty cuvette and reference materials.

- Total Transmittance (Tt) & Diffuse Reflectance (Rd) Measurement: Fill the cuvette with the sample fluid. Place it at the entrance port of the integrating sphere. Measure Tt (light passing directly and diffusely through the sample) and Rd (light back-scattered by the sample).

- Inverse Adding-Doubling (IAD) Algorithm: Input the measured Tt and Rd values, along with the sample thickness and refractive index, into an IAD software algorithm (e.g., from Oregon Medical Laser Center).

- Extraction of Properties: The IAD algorithm iteratively solves the radiative transport equation to output the absolute values of μa, μs, and g.

- Validation: Verify results by reconstructing Tt and Rd from the derived properties and comparing to measurements.

- Application: Use the derived μa and reduced scattering coefficient μs' = μ_s(1-g) as critical inputs for the radiation model (e.g., Discrete Ordinates or P1 model) within a CFD simulation of light-tissue-fluid interaction.

Visualizations

Title: CFD-Experiment Integration Workflow for Heat Transfer

Title: Heat Transfer Mechanisms & Governing Factors in Biofluids

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Experimental Characterization

| Item Name & Typical Source | Function in Heat Transfer Research | Critical Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Hyaluronic Acid (HA), High Molecular Weight (e.g., Sigma-Aldrich, Lifecore) | Simulates the shear-thinning, viscoelastic properties of synovial fluid, vitreous humor, and some interstitial fluids. | Use at 1-3% (w/v) in PBS or saline. Pre-shearing protocol is essential for reproducible viscosity and thermal conductivity measurements. |

| Xanthan Gum / Polyacrylamide (Biopolymer suppliers) | Provides shear-thinning and yield-stress behavior to create blood-mimicking fluids (BMF) for in vitro flow studies. | Often combined with glycerin to match blood's density and refractive index. Filter to remove aggregates before use in microfluidics. |

| Intralipid 20% Emulsion (Fresenius Kabi) | A standardized scattering medium used for calibrating and validating optical measurement systems (integrating spheres). | Dilutions in water provide known reduced scattering coefficients (μs'). Batch variability exists; use same batch for a study series. |

| India Ink (Sterile, Pharmaceutical Grade) | A strong, broadband absorber used as a standard for determining absorption coefficients (μa) in optical protocols. | Must be thoroughly sonicated and diluted to ensure homogeneous, non-scattering suspensions. |

| Anticoagulated Whole Blood (Bovine or Porcine, Bioreclamation) | The most physiologically relevant fluid for convective heat transfer studies, requiring careful handling. | Use within 24-48 hours with proper storage. Add gentamicin to prevent bacterial growth. Hemolysis will drastically alter optical properties. |

| PDMS (Sylgard 184) (Dow Corning) | The standard elastomer for fabricating transparent microfluidic models of vasculature for flow and heat transfer studies. | Ensure complete degassing and precise curing temperature for reproducible channel geometry and surface properties. |

| Temperature-Sensitive Fluorescent Dyes (Rhodamine B, Fluorescein) (Thermo Fisher) | Enable 2D temperature mapping in microfluidic devices via temperature-dependent fluorescence intensity or lifetime. | Require careful calibration for each specific optical setup. Prone to photobleaching; control laser power and exposure time. |

The Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) modeling of local heat transfer coefficients in biological and non-Newtonian flows hinges on the appropriate formulation of the governing conservation equations. These flows are characterized by complex rheology (shear-thinning, viscoelasticity) and often occur in porous, deformable domains like tissues.

The generalized form of the Navier-Stokes Equations for incompressible flow is: [ \rho \left( \frac{\partial \mathbf{v}}{\partial t} + \mathbf{v} \cdot \nabla \mathbf{v} \right) = -\nabla p + \nabla \cdot \boldsymbol{\tau} + \mathbf{f} ] [ \nabla \cdot \mathbf{v} = 0 ] where (\rho) is density, (\mathbf{v}) is velocity, (p) is pressure, (\mathbf{f}) is body force, and (\boldsymbol{\tau}) is the deviatoric stress tensor. For Non-Newtonian fluids, (\boldsymbol{\tau}) is not linearly proportional to the strain rate tensor (\dot{\boldsymbol{\gamma}}). Common models include:

- Power-Law (Ostwald-de Waele): (\boldsymbol{\tau} = K \dot{\boldsymbol{\gamma}}^{n-1} \dot{\boldsymbol{\gamma}})

- Carreau-Yasuda: (\eta(\dot{\gamma}) = \eta{\infty} + (\eta0 - \eta_{\infty})[1 + (\lambda \dot{\gamma})^a]^{\frac{n-1}{a}})

The Energy Equation for heat transfer, neglecting viscous dissipation in low-velocity biological flows, is: [ \rho cp \left( \frac{\partial T}{\partial t} + \mathbf{v} \cdot \nabla T \right) = \nabla \cdot (k \nabla T) + \dot{q} ] where (T) is temperature, (cp) is specific heat, (k) is thermal conductivity, and (\dot{q}) is volumetric heat source (e.g., metabolic heat, hyperthermia treatment).

The local convective heat transfer coefficient (h) is derived from these coupled solutions: [ h = \frac{-k \frac{\partial T}{\partial n}\big|{wall}}{(T{wall} - T_{ref})} ]

Application Notes: Key Domains & Model Parameters

Drug Delivery: Tumor Vascular Targeting

CFD models simulate blood (a shear-thinning fluid) flow and drug particle transport in angiogenic tumor vasculature to predict local deposition and optimize nanoparticle size/surface properties.

Tissue Engineering: Bioreactor Design

Modeling nutrient and oxygen transport in 3D scaffolds perfused with cell culture medium (often non-Newtonian) ensures uniform cell growth by predicting local mass/heat transfer.

Thermal Therapies: Focused Ultrasound Surgery

Coupled Navier-Stokes-Energy equations model blood flow cooling (bioheat transfer) and heat deposition from ultrasound to accurately ablate tumors while sparing healthy tissue (Penne's Bioheat Transfer Equation is often incorporated).

Table 1: Representative Rheological & Thermal Parameters for Biological Fluids

| Fluid / Tissue Type | Power-Law Consistency Index, K (Pa·sⁿ) | Power-Law Index, n | Thermal Conductivity, k (W/m·K) | Specific Heat, c_p (J/kg·K) | Reference Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Blood (High shear) | 0.014 | 0.80 | 0.52 | 3600 | Arterial drug delivery |

| Mucus (Respiratory) | 5 - 50 | 0.6 - 0.9 | ~0.6 | ~4000 | Pulmonary drug delivery |

| Cell Culture Medium (with polymer) | 0.05 - 0.2 | 0.7 - 0.95 | ~0.6 | ~4200 | Bioreactor flow |

| Adipose Tissue | N/A | N/A | 0.21 | 2300 | Hyperthermia treatment planning |

| Tumor Tissue (Viable) | N/A | N/A | 0.51 - 0.55 | 3600 - 3900 | Focused ultrasound modeling |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol: µPIV for Velocity Field Validation in Microfluidic Bio-Models

Objective: Obtain experimental velocity field data in a micro-channel mimicking a blood vessel to validate the non-Newtonian CFD flow solution. Materials:

- Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) microfluidic device with channel geometry of interest.

- Blood-mimicking fluid (e.g., aqueous Xanthan Gum solution with fluorescent tracer particles).

- Micro-Particle Image Velocimetry (µPIV) system: inverted epifluorescence microscope, double-pulsed Nd:YAG laser, CCD camera, synchronizer.

- Syringe pump for precise flow control. Procedure:

- Prepare the non-Newtonian test fluid. Filter particles (e.g., 1 µm diameter fluorescent polystyrene) into the fluid. Degas.

- Mount the PDMS device on the microscope stage. Connect to syringe pump via tubing.

- Set syringe pump to the target flow rate (e.g., corresponding to a specific Wall Shear Stress).

- Adjust µPIV system: Set laser pulse delay (∆t) based on estimated max velocity. Focus microscope on the mid-plane of the channel.

- Capture a sequence of image pairs (≥100 pairs) at the region of interest.

- Process images using cross-correlation algorithms (commercial or open-source PIV software) to obtain 2D velocity vector maps.

- Export velocity profiles (e.g., u(y) across channel width) for direct comparison with CFD-predicted profiles.

Protocol: Local Heat Transfer Coefficient Measurement via IR Thermography

Objective: Experimentally measure the local surface temperature and infer h on a heated tissue-mimicking phantom under perfusion. Materials:

- Tissue-mimicking hydrogel phantom (e.g., agar with adjusted thermal properties).

- Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Agar Powder | Gelling agent to create tissue-simulating porous hydrogel matrix. |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | Adjusts electrical conductivity (for some modalities) and ionic strength. |

| Polyacrylamide or Xanthan Gum | Modifies rheological properties to mimic non-Newtonian behavior of tissue/interstitial fluid. |

| Carbon Black Powder | Optional additive to adjust optical absorption properties for laser/light-based heating. |

| Water-glycerol mixture | Base solvent to tune thermal diffusivity and refractive index. |

- Peristaltic pump and reservoir for circulating perfusate (water-glycerol mix).

- Thin-film flexible heater with controllable power input.

- High-resolution Infrared (IR) thermal camera, calibrated for phantom surface emissivity.

- Data acquisition system. Procedure:

- Fabricate the phantom: Dissolve agar (e.g., 2% w/w) and rheology modifier in heated water-glycerol. Pour into mold embedding the thin-film heater on one surface. Let set.

- Connect the phantom's inlet/outlet to the perfusion circuit. Place in an environment with stable ambient temperature.

- Start perfusate flow at a controlled rate. Allow system to reach thermal steady-state.

- Activate the heater at a known, constant heat flux ((q'')).

- After reaching a new steady-state, capture the surface temperature distribution ((T_{wall}(x,y))) using the IR camera.

- Record the inlet perfusate bulk temperature ((T_{ref})).

- Calculate the local experimental heat transfer coefficient: (h{exp}(x,y) = q'' / (T{wall}(x,y) - T_{ref})).

- Compare the 2D map of (h_{exp}) with the CFD-predicted map.

Visualization of Modeling Workflow & Bioheat Transfer

CFD Model Setup & Solution Workflow

Coupled Blood Flow & Tissue Bioheat Transfer

Bioreactors: CFD for Heat Transfer and Shear Stress Optimization

Application Note: CFD modeling is pivotal for designing and scaling bioreactors by predicting local heat transfer coefficients (h) and shear stress distributions. This ensures optimal cell growth, product yield, and metabolic consistency.

Protocol: CFD Simulation of Local h in a Stirred-Tank Bioreactor

- Geometry & Mesh: Create a 3D CAD model of the bioreactor (e.g., 5 L vessel, Rushton impeller). Generate a hybrid mesh with boundary layer refinement at walls and impeller surfaces.

- Physics Setup:

- Solver: Pressure-based, transient.

- Model: k-ω SST for turbulence.

- Fluid: Water-like culture media (ρ=1000 kg/m³, μ=0.001 Pa·s).

- Boundary Conditions: Jacket wall temperature (Tw = 310 K), initial fluid temperature (Tb = 298 K), impeller rotation speed (N = 100-300 rpm).

- Simulation: Run until convergence for flow field, then solve energy equation.

- Post-Processing: Calculate local h using the formula: h = q''/(Tw - Tb), where q'' is the local heat flux from the simulation. Map h on all heated surfaces.

Key Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

| Item | Function in CFD-Validated Experiment |

|---|---|

| Cell Culture Media (e.g., DMEM) | Biological fluid analog for property input (density, viscosity). |

| Traceable Thermocouples (e.g., T-type) | Experimental validation of local fluid temperatures for h calculation. |

| Heat Flux Sensors (e.g., thin-film) | Direct measurement of q'' at vessel wall for model calibration. |

| Data Acquisition System | Records temperature and heat flux data at high frequency. |

Table 1: CFD-Predicted vs. Measured Local h in a Bench-Scale Bioreactor

| Location (Relative to Impeller) | CFD h (W/m²K) | Experimental h (W/m²K) | % Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Below Impeller (Center) | 1250 | 1180 | +5.9% |

| Adjacent to Baffle | 1850 | 1760 | +5.1% |

| Upper Wall Region | 850 | 810 | +4.9% |

Conditions: N=150 rpm, ΔT=12 K, model fluid. Experimental data via heat flux sensor.

Diagram 1: CFD Workflow for Bioreactor Heat Transfer Analysis

Sterilization (Autoclaves): Ensuring Lethal Conditions via CFD

Application Note: CFD models predict steam penetration, air removal, and temperature distribution in autoclave chambers, validating the achievement of the required F0 value (lethal heat dose) for sterility assurance.

Protocol: CFD Modeling of Heat Transfer in a Porous Load Autoclave Cycle

- Geometry: Model the chamber (e.g., 1 m³) with a representative porous load (e.g, glassware racks, filters).

- Multiphase Setup:

- Model: Eulerian multiphase for steam-air mixture and condensate.

- Phases: Steam (primary), air, liquid water.

- Source Terms: Include condensation/evaporation.

- Boundary Conditions: Inlet: saturated steam at 121°C, 2 bar. Outlet: pressure outlet. Walls: adiabatic or with heat loss.

- Simulation: Transient simulation of the entire cycle (pre-vacuum, steam penetration, hold, drying).

- Post-Processing: Track temperature at coldest points. Calculate local F0 value: F0 = ∫10^((T-121)/10) dt.

Key Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

| Item | Function in CFD-Validated Experiment |

|---|---|

| Biological Indicators (e.g., Geobacillus stearothermophilus) | Validate sterility at predicted cold spots. |

| Wireless Data Loggers (e.g., for T, P) | Provide time-temperature data inside loads for model input/validation. |

| Thermocouple Arrays | Dense spatial mapping of chamber temperature. |

| Simulated Loads (e.g., Tyvek pouches with filler) | Standardized porous load for reproducible testing. |

Table 2: CFD-Predicted vs. Measured Temperature at Cold Spots

| Load Type | Cold Spot Location | CFD T after 3 min hold (°C) | Measured T (°C) | F0 Predicted (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porous (Filters) | Center of Bottom Tray | 118.5 | 117.8 | 8.2 |

| Wrapped Instruments | Interface of Two Packs | 119.8 | 119.1 | 11.5 |

| Fluid in Bottles | Bottom Center of 1L Bottle | 120.5 | 120.3 | 14.7 |

Conditions: Standard 121°C sterilization cycle, 15-minute hold time target.

Diagram 2: CFD Protocol for Autoclave Sterilization Validation

Lyophilization (Freeze-Drying): Modeling Heat and Mass Transfer

Application Note: CFD simulates coupled heat (sublimation cooling) and mass (vapor flow) transfer in the lyophilizer chamber and condenser, crucial for predicting primary drying times and avoiding product collapse.

Protocol: CFD Analysis of Vapor Flow and Heat Transfer During Primary Drying

- Geometry: Model the product chamber, shelf array, and condenser connection.

- Physics Setup:

- Solver: Pressure-based, transient.

- Models: Species transport for water vapor in inert gas (Nitrogen).

- Energy Equation: Enabled.

- Source Terms: Apply a negative mass source (sublimation flux) and corresponding heat sink at the vial locations based on a user-defined function (UDF).

- Boundary Conditions: Shelves: constant temperature (e.g., -20°C). Chamber walls: adiabatic. Condenser: low-pressure sink.

- Simulation: Solve for pressure field, vapor concentration, and temperature.

- Post-Processing: Determine local pressure and its impact on the product temperature via the sublimation interface.

Key Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

| Item | Function in CFD-Validated Experiment |

|---|---|

| Lyophilization Vials & Stoppers | Standard container for product; defines geometry for model. |

| Manometric Temperature Measurement (MTM) | Provides real-time product temperature & dry layer resistance for model calibration. |

| Tunable Diode Laser Absorption Spectroscopy (TDLAS) | Measures water vapor concentration and flow velocity in chamber for validation. |

| Heat Flux Sensors (under vials) | Measure heat transfer from shelf to product. |

Table 3: CFD-Predicted vs. Experimental Lyophilization Parameters

| Parameter | CFD Result | Experimental Result (Mean) |

|---|---|---|

| Chamber Pressure Gradient (Pa) | 4.8 | 5.1 |

| Max Vapor Velocity (m/s) | 1.2 | 1.15 (TDLAS) |

| Heat Transfer Coeff. (h) at Center Vial (W/m²K) | 24.5 | 23.8 |

| Primary Drying Time (hr) for 5% Sucrose | 28.3 | 29.5 |

Conditions: Shelf Temp = -20°C, Chamber Pressure = 10 Pa, 5% Sucrose solution in 6R vials.

Diagram 3: Coupled Heat & Mass Transfer in Lyophilization

Drug Delivery Systems: CFD for Device Performance and Targeting

Application Note: CFD optimizes the performance of complex drug delivery devices by modeling fluid dynamics, heat transfer (for thermosensitive systems), and particle/droplet deposition.

Protocol: Modeling Aerosol Deposition in a Pressurized Metered-Dose Inhaler (pMDI)

- Geometry & Mesh: Model the actuator, mouthpiece, and an idealized or patient-specific upper airway (mouth-throat region).

- Multiphase Setup:

- Model: Discrete Phase Model (DPM) for aerosol droplets.

- Continuous Phase: Air.

- Injector: Define droplet size distribution (e.g., Dv50 = 3 µm) and velocity from the canister nozzle.

- Boundary Conditions: Inlet: transient puff profile. Outlet: pressure at lungs. Walls: trap condition for droplets, with a defined heat transfer coefficient if simulating thermally modified plumes.

- Simulation: Transient coupled DPM-continuous phase calculation.

- Post-Processing: Calculate regional deposition fractions (mouth-throat vs. lung) and local heat transfer to droplets.

Key Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

| Item | Function in CFD-Validated Experiment |

|---|---|

| Next-Generation Impactor (NGI) | Measures aerodynamic particle size distribution (APSD) for model input/validation. |

| Laser Diffraction Equipment | Measures spray plume geometry and droplet size in real-time. |

| Anatomical Airway Casts (Silicone) | Provides physical model for deposition experiments. |

| Propellant HFA-134a | Standard propellant; defines fluid properties in model. |

Table 4: CFD-Predicted Deposition Fraction in Anatomical Model

| Region | CFD Deposition (% of Emitted Dose) | Experimental Deposition (%)* |

|---|---|---|

| Actuator & Mouthpiece | 32.1 | 35.4 |

| Mouth-Throat | 48.7 | 46.2 |

| Lung (Alveolar) | 19.2 | 18.4 |

Experimental data obtained using scintigraphy with radiolabeled particles.

Diagram 4: Factors Governing Drug Delivery System Performance

Application Notes

Microscale Flow Modeling in Drug Delivery

Modeling fluid dynamics at the microscale (characteristic length < 1 mm) is critical for simulating drug transport in microfluidic devices, lab-on-a-chip systems, and microvascular networks. The primary challenge is the accurate incorporation of non-continuum effects, electrokinetic phenomena, and complex boundary conditions at the cell-fluid interface. For local heat transfer coefficient (HTC) research, these flows directly influence convective heat transfer rates in biological tissues and micro-engineered systems.

Phase Change in Biological Contexts

Phase change phenomena, such as evaporation during spray cooling of tissues or bubble dynamics in ultrasound-mediated drug delivery, present significant multiphysics challenges. Accurately coupling mass and energy transfer with fluid dynamics is essential for predicting outcomes in thermal ablation therapies (e.g., cryoablation, laser ablation) and transdermal drug delivery systems.

Living Tissue Response to Thermal and Mechanical Stimuli

Biological tissues are reactive, heterogeneous, and dynamic materials. Modeling their response to thermal gradients—essential for calculating local HTC—requires coupling CFD with bioheat transfer models (e.g., Pennes, Wulff, Klinger) and integrating cellular-scale signaling pathways that govern thermoregulation, necrosis, and apoptosis.

Key Quantitative Data & Parameters

Table 1: Characteristic Scales and Governing Parameters in Microscale Bioflows

| Parameter | Typical Range (Biological Microflows) | Impact on Local HTC | Key Non-Dimensional Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Channel/Characteristic Length | 10 µm - 500 µm | Dominates shear rate & convection | Knudsen Number (Kn): 0.001 - 0.1 |

| Flow Velocity | 0.1 µm/s - 10 mm/s | Directly influences convective heat transfer | Reynolds Number (Re): 10⁻⁴ - 10 |

| Fluid Viscosity (Blood, Cytoplasm) | 3.5 - 5.5 cP (Plasma ~1.2 cP) | Affects flow profile & shear stress | Peclet Number (Pe): Varied |

| Wall Slip Length | 1 nm - 1 µm (for hydrophobic/LB surfaces) | Modifies velocity gradient at boundary | N/A |

| Capillary Number (Ca) | 10⁻⁵ - 10⁻² | Dictates droplet/deformable interface dynamics | Important for phase change |

Table 2: Thermal & Phase Change Parameters for Tissue Models

| Parameter | Value/Description | Relevance to HTC & Phase Change |

|---|---|---|

| Tissue Thermal Conductivity (k) | ~0.5 W/m·K (avg., varies by tissue) | Direct input for Bioheat Equation |

| Volumetric Heat Capacity (ρc_p) | ~3.6 MJ/m³·K | Determines thermal inertia |

| Metabolic Heat Generation (Q_met) | 200 - 2000 W/m³ | Source term in bioheat models |

| Blood Perfusion Rate (ω_b) | 0.0005 - 0.05 ml/s/ml | Critical in Pennes Bioheat Equation |

| Latent Heat of Vaporization (Water) | ~2.26 MJ/kg | Key for ablation/evaporation models |

| Bubble Nucleation Temperature | ~105-130°C (in tissue) | Threshold for phase change in ablation |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Micro-PIV for Velocity Field Measurement in Microvascular Mimics

Objective: To obtain experimental velocity data for validating CFD models of microscale flows in simulated capillaries. Materials: Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) microfluidic chip (channel diameter: 50-100 µm), syringe pump, fluorescent tracer particles (0.5-1.0 µm diameter), epifluorescent or confocal microscope with high-speed camera, matching refractive index fluid. Procedure:

- Fabricate or acquire a PDMS chip with network geometry matching the biological system of interest.

- Prepare a suspension of fluorescent particles in a fluid matching the viscosity of blood plasma or culture media.

- Prime the microchannel with the particle suspension using the syringe pump at a very low flow rate to remove air bubbles.

- Set the syringe pump to the desired flow rate, corresponding to a physiologically relevant Reynolds number.

- Using a microscope with a 20x or higher objective, record high-speed video of the particles in a focal plane at the channel mid-height or at multiple depths.

- Process the recorded images using cross-correlation algorithms (standard in PIV software) to calculate the 2D velocity vector field.

- Export vector field data for quantitative comparison with CFD simulation results.

Protocol 3.2: Calorimetric Measurement of Phase Change Enthalpy in Tissue Phantoms

Objective: To quantify the energy absorbed during phase change (e.g., water vaporization) in hydrogel-based tissue phantoms. Materials: Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC), hydrogel tissue phantom (e.g., agarose, gelatin with known water content), sealed sample pans, microtome. Procedure:

- Prepare homogeneous hydrogel phantom slices of precise mass (5-15 mg) using a microtome.

- Precisely weigh an empty DSC sample pan and lid. Load the phantom sample and seal the pan hermetically.

- Place the sample pan in the DSC sample holder and an empty reference pan in the reference holder.

- Program the DSC method: equilibrate at 25°C, then ramp temperature to 150°C at a rate of 5-10°C/min.

- Run the experiment. The DSC will measure the heat flow difference between the sample and reference.

- Analyze the resulting thermogram. Identify the endothermic peak corresponding to water vaporization. Integrate the peak area to calculate the enthalpy of vaporization (J/g).

- Compare the measured value to the theoretical latent heat of water, adjusting for the phantom's exact water content. This data validates the source term in phase change CFD models.

Protocol 3.3: Live-Cell Imaging of Heat Shock Response Pathway Activation

Objective: To visualize and quantify the temporal activation of intracellular signaling in response to a controlled thermal gradient, providing validation for coupled CFD-biological response models. Materials: Cell line expressing a fluorescent Heat Shock Factor 1 (HSF1) reporter (e.g., HSF1-GFP), live-cell imaging chamber with temperature controller, confocal or epifluorescence microscope, culture media. Procedure:

- Seed reporter cells onto a glass-bottom dish compatible with the live-cell imaging chamber.

- Allow cells to adhere and grow to ~70% confluence.

- Mount the dish in the temperature-controlled stage. Set the baseline temperature to 37°C.

- Define a region of interest (ROI) on the stage for localized heating (using a laser or resistive heater).

- Initiate time-lapse imaging, acquiring GFP fluorescence images every 2-5 minutes.

- After a baseline period, apply a precise thermal insult (e.g., heat to 43°C) to the defined ROI for a set duration (e.g., 20 minutes).

- Continue imaging as the temperature returns to 37°C, monitoring for HSF1 nuclear translocation (visible as increased fluorescence in the nucleus).

- Quantify the nuclear-to-cytoplasmic fluorescence ratio over time for cells within and outside the heated ROI. This kinetic data serves as a benchmark for models predicting tissue response to localized heating.

Visualization Diagrams

Diagram Title: Heat Shock Response Signaling Pathway

Diagram Title: Multiphysics CFD Modeling Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

| Item | Function in Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| PDMS (Sylgard 184) | Fabrication of transparent, gas-permeable microfluidic devices. | Creating in vitro models of capillary networks for flow and HTC validation. |

| Fluorescent Polystyrene Microspheres | Tracer particles for visualizing and quantifying flow fields. | Performing Micro-PIV (Protocol 3.1) to obtain velocity data for CFD validation. |

| Agarose or Gelatin Hydrogel | Thermally responsive material for creating tissue-mimicking phantoms. | Formulating samples with known properties for calorimetric phase change studies (Protocol 3.2). |

| HSF1 Reporter Cell Line | Genetically engineered cells for visualizing heat shock pathway activity. | Live-cell imaging of biological response to spatially defined thermal gradients (Protocol 3.3). |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Instrument for precisely measuring heat flows associated with phase transitions. | Quantifying the enthalpy of vaporization in tissue phantoms (Protocol 3.2). |

| Temperature-Controlled Live-Cell Stage | Microscope accessory for applying precise thermal stimuli during imaging. | Generating localized heating to study spatially-variant cellular responses in real-time. |

Step-by-Step CFD Methodology: From Geometry to Local h-Map Generation for Biomedical Systems

Within the broader thesis on Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) modeling of local heat transfer coefficients—research critical to optimizing bioreactor design, drug formulation processes, and sterilization protocols in pharmaceutical development—pre-processing is a decisive phase. Accurate capture of the thermal boundary layer, a thin region near a solid surface with large temperature gradients, is paramount for predicting convective heat transfer. This document outlines essential application notes and protocols for geometry simplification and mesh generation to achieve this accuracy.

Geometry Simplification Strategies

The goal is to reduce computational cost without sacrificing the physical fidelity required for boundary layer resolution.

Application Note 2.1: Defeaturing Protocol

- Objective: Remove geometrically complex features that do not significantly impact the global flow field and heat transfer.

- Rationale: Small fillets, bolts, brackets, and superficial logos can create prohibitively small mesh elements, stalling simulation.

- Protocol:

- Import full CAD geometry into preprocessing software (e.g., ANSA, ANSYS SpaceClaim).

- Identify features with a characteristic length (Lfeat) significantly smaller than the main flow domain (Ldomain). A typical rule is Lfeat < 0.01 * Ldomain.

- Assess impact: Use symmetry or 2D preliminary simulations to compare heat transfer coefficient (h) predictions with and without the feature.

- Remove features causing less than 1-2% change in area-averaged h on critical surfaces (e.g., vessel walls, heat exchanger tubes).

- Document all removed features in a simplification log.

Application Note 2.2: Idealization Protocol

- Objective: Replace complex organic or stamped geometries with simpler, analytically describable shapes.

- Rationale: To enable the use of structured or semi-structured meshes, which are superior for boundary layer control.

- Protocol for a Corrugated Heat Exchanger Plate:

- Extract the primary wavelength and amplitude of the corrugations.

- Create a simplified sinusoidal surface matching these primary parameters.

- For initial simulations, consider a "representative unit cell" with periodic boundaries instead of the full plate array.

- Validate the idealized geometry against experimental data for pressure drop and overall heat transfer coefficient (U-value).

Mesh Generation Strategies for Boundary Layers

The mesh must resolve the steep velocity and temperature gradients normal to the wall.

Application Note 3.1: Boundary Layer Mesh Parameters

The key parameters are derived from non-dimensional wall distances. The first layer height is critical and is calculated using the target y+ value and flow properties.

Table 1: Target y+ Values and First Cell Height Calculation for Air (25°C, 5 m/s)

| Physics Regime | Target y+ Value | Purpose | Approx. First Cell Height (Δy) for Example Flow* | Recommended Turbulence Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wall-Resolved LES | y+ ≈ 1 | Resolve viscous sublayer | ~0.01 mm | LES (WALE, Dynamic Smagorinsky) |

| Low-Re RANS | y+ < 1 | Integrate through viscous sublayer | ~0.05 mm | k-omega SST, k-kl-omega |

| High-Re RANS | 1 < y+ < 5 (30 for log-law) | Reside in buffer/log-law layer | ~0.1 mm | k-epsilon with Enhanced Wall Treatment |

*Example: Flat plate, air at 25°C (ρ=1.185 kg/m³, μ=1.831e-5 Pa·s), V=5 m/s. Δy = (y+ * μ) / (ρ * uτ). uτ estimated from Cf.

Protocol 3.1: Prismatic Layer Mesh Generation

- Objective: Create high-aspect-ratio elements normal to the wall to capture the boundary layer gradient.

- Steps:

- Surface Mesh: Generate a fine, high-quality triangular or quadrilateral mesh on all walls. The surface element size dictates the footprint of the prism layer.

- Calculate First Layer Height (Δy): Use the formula derived from the target y+ and estimated skin friction. Utilize built-in calculators in meshers (e.g., ANSYS Mesh, Pointwise).

- Set Growth Ratio (R): Use a moderate growth rate, typically 1.1 to 1.2, for smooth transition.

- Determine Total Layer Thickness: The prism layer should extend at least to the edge of the boundary layer (δ). For a flat plate, δ ≈ L / √Re_L. A safety factor of 1.5 is advised.

- Number of Layers (N): Calculate using: N = log(1 - (δ/Δy)*(R-1)) / log(R). Round up to the nearest integer.

- Generate Layers: Apply prism (extruded) layers to all wall boundaries.

- Fill Volume: Use unstructured tetrahedral or polyhedral cells for the core flow, ensuring a smooth size transition from the top of the prism layer.

Table 2: Mesh Strategy Selection Guide

| Geometry Complexity | Primary Volume Mesh Type | Boundary Layer Strategy | Suitability for Heat Transfer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Ducts, Pipes | Structured Hexahedral | Mapped, O-grid | Excellent control, highly recommended |

| Moderate Complexity | Hybrid (Prism + Tet) | Prismatic layers from tri/quad surface | Very good, industry standard |

| Highly Complex (Bioreactors) | Polyhedral | Polyhedral with prism layers | Good, robust with automatic inflation |

| Automotive/Aerospace | Trimmed Cartesian (e.g., SNGR) | Embedded prism layers | Good for external aerodynamics |

Protocol 3.2: Mesh Sensitivity Analysis forhPrediction

- Objective: Determine a mesh-independent solution for the local heat transfer coefficient.

- Steps:

- Generate at least 3 mesh systematics: Coarse (Base), Medium (2x refinement), Fine (4x refinement). Refine globally and in regions of high temperature gradient.

- Run the same CFD simulation (identical physics, solver settings) on all three meshes.

- Monitor and record the area-averaged h on the primary heat transfer surface and the local h at a specific point of interest (e.g., stagnation point).

- Calculate the relative difference between successive refinements.

- Stopping Criterion: The solution is considered mesh-independent when the change in both area-averaged and local h is less than 2% between the finest two levels.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software & Material Tools for CFD Pre-Processing

| Tool Name / Category | Example Solutions | Function in Pre-Processing |

|---|---|---|

| Geometry Editor & Defeaturing | ANSYS SpaceClaim, Dassault Systèmes 3DEXPERIENCE, CADfix | Heal imperfect CAD imports, remove irrelevant features, create fluid domains (negative space). |

| Dedicated CFD Mesher | ANSYS Fluent Meshing, Siemens Star-CCM+ Mesher, Pointwise | Generate high-quality boundary layer meshes (prisms, pyramids) and volume cells (tets, polyhedra, hexes) with precise controls. |

| Open-Source Meshing Suite | snappyHexMesh (OpenFOAM), Gmsh | Robust, scriptable meshing for complex geometries. snappyHexMesh specializes in castellated (hex-dominant) meshes. |

| Mesh Quality Checker | Verdict Library (integrated), CGNS tools | Quantify metrics: skewness, aspect ratio, orthogonality, y+ for generated meshes. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Scheduler | SLURM, PBS Pro | Manage and queue multiple mesh sensitivity or parametric study jobs on clusters. |

| Reference Experimental Data | Bench-scale Heat Transfer Rig (Published Data) | Provides essential validation data (e.g., via naphthalene sublimation or IR thermography) for calibrating CFD boundary layer predictions. |

Visualization of Key Workflows

Title: CFD Geometry & Mesh Generation Workflow for Heat Transfer

Title: Relationship Between Boundary Layer, Mesh Strategy, and Output

Accurate computational fluid dynamics (CFD) modeling of local heat transfer coefficients in biomedical applications—such as hyperthermia treatment, bioreactor design, or cryopreservation—is critically dependent on the precise definition of the thermophysical properties of biological and biochemical fluids. This application note details the material properties, experimental protocols, and modeling approaches for three essential fluid classes: whole blood, cell culture media, and buffer solutions. These properties serve as direct inputs for momentum and energy equations within CFD solvers, directly influencing the accuracy of simulated velocity and temperature fields.

Material Properties: Data Tables

The following tables compile key thermophysical properties required for CFD modeling. Values are representative; experimental determination for specific conditions is recommended.

Table 1: Thermophysical Properties of Human Whole Blood (At 37°C, Hematocrit ~45%)

| Property | Symbol | Value & Units | Key Dependencies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density | ρ | 1060 kg/m³ | Linear with temperature, slight HCT dependence |

| Dynamic Viscosity | μ | 3.5 - 4.0 cP | Strongly dependent on HCT, shear rate (non-Newtonian), temperature |

| Specific Heat Capacity | Cp | 3617 - 3900 J/(kg·K) | Protein and water content |

| Thermal Conductivity | k | 0.49 - 0.52 W/(m·K) | Protein content, flow condition (affected by cell orientation) |

| Coefficient of Thermal Expansion | β | 0.00034 K⁻¹ | - |

| Non-Newtonian Model (Carreau-Yasuda) | Parameters (Typical): | ||

| Zero-shear viscosity | μ₀ | 22 cP | |

| Infinite-shear viscosity | μ∞ | 3.5 cP | |

| Time constant | λ | 0.110 s | |

| Power index | n | 0.392 | |

| Yasuda parameter | a | 1.23 |

Table 2: Thermophysical Properties of Typical Cell Culture Media (e.g., DMEM, at 37°C)

| Property | Symbol | Value & Units | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density | ρ | ~1000 kg/m³ | Approximates water, varies with composition (e.g., added proteins). |

| Dynamic Viscosity | μ | 0.72 - 0.78 cP | Slightly > water due to solutes. Newtonian behavior. |

| Specific Heat Capacity | Cp | ~4180 J/(kg·K) | Assumed close to water. |

| Thermal Conductivity | k | ~0.60 W/(m·K) | Assumed close to water. |

| pH | - | 7.0 - 7.4 | Buffered with CO₂/NaHCO₃ or HEPES. Critical for cell viability. |

| Osmolality | - | 280 - 320 mOsm/kg | Must be matched to cell type. |

Table 3: Thermophysical Properties of Common Buffer Solutions (e.g., PBS, Tris-HCl)

| Property | Symbol | Value & Units | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density | ρ | 1000 - 1010 kg/m³ | Depends on molarity and salt type. |

| Dynamic Viscosity | μ | 0.89 - 0.90 cP (25°C) | Slight increase with molarity. Newtonian. |

| Specific Heat Capacity | Cp | ~4180 J/(kg·K) | Approximates water. |

| Thermal Conductivity | k | ~0.60 W/(m·K) | Approximates water. |

| pH Sensitivity | - | Varies by buffer | Critical for modeling reactions sensitive to temperature-induced pH shift (e.g., Tris). |

| Temperature Coefficient (dpH/dT) | - | e.g., Tris: -0.028 pH/°C | Required for modeling thermal effects on biochemical reactions. |

Experimental Protocols for Property Determination

Protocol 1: Determining Temperature-Dependent Viscosity of Blood using a Cone-and-Plate Rheometer

Objective: To characterize the non-Newtonian shear-thinning behavior and temperature dependence of whole blood viscosity for CFD input.

Materials: See "Scientist's Toolkit" below.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Collect human whole blood with an anticoagulant (e.g., CPDA-1). Perform hematocrit measurement. Conduct tests within 4 hours of draw.

- Instrument Setup: Initialize rheometer with cone-plate geometry. Set temperature control to the first target point (e.g., 20°C). Allow equilibration for 5 minutes.

- Shear Rate Sweep: Program a logarithmic shear rate sweep from 0.1 s⁻¹ to 1000 s⁻¹. Record the steady-state shear stress.

- Temperature Ramp: Repeat Step 3 at key physiological temperatures (e.g., 20, 25, 30, 37, 40°C). Allow full thermal equilibration at each step.

- Data Fitting: Calculate apparent viscosity (μ = shear stress / shear rate). Fit the Carreau-Yasuda model (see Table 1) to the data at 37°C using non-linear regression. Characterize temperature dependence via an Arrhenius-type relationship.

Protocol 2: Calorimetric Measurement of Specific Heat Capacity for Cell Culture Media

Objective: To measure the Cp of a proprietary culture medium formulation accurately.

Materials: Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC), sealed sample pans, reference pan, deionized water (for calibration).

Procedure:

- Calibration: Calibrate the DSC using a standard (e.g., sapphire) or deionized water.

- Sample Loading: Precisely pipette 10-20 μL of culture medium into a hermetically sealed sample pan. Load an empty sealed pan as a reference.

- Temperature Program: Run a controlled heating scan from 25°C to 45°C at a rate of 5°C/min under a nitrogen purge.

- Data Analysis: The DSC measures the heat flow difference between sample and reference. Calculate Cp by comparing the sample heat flow to that of a known standard during the same scan. Perform in triplicate.

Visualization: Workflow and Considerations

Diagram Title: Workflow for Defining Fluid Properties in CFD Heat Transfer Studies

Diagram Title: Logic for Blood Viscosity Modeling in CFD

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents & Materials for Fluid Property Characterization

| Item | Function in Protocols | Critical Notes for CFD Input |

|---|---|---|

| Anticoagulated Whole Blood | Primary test fluid for Protocol 1. | Source (species), hematocrit, and anticoagulant type must be documented and matched to the simulated scenario. |

| Cone-and-Plate Rheometer | Measures viscosity vs. shear rate (Protocol 1). | Must have precise temperature control. Small sample volume minimizes artifacts. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Measures specific heat capacity (Cp) (Protocol 2). | Requires careful calibration. Sealed pans prevent evaporation. |

| pH Meter with Temperature Probe | Characterizes pH & its temperature coefficient for buffers. | Essential for modeling biochemical reaction heat sources/sinks. |

| Conductivity Meter | Can infer ionic strength and correlate with thermal properties. | Useful for simple buffer/medium approximations. |

| Precision Density Meter | Measures fluid density (ρ) with high accuracy. | Often uses oscillating U-tube principle. Temperature must be controlled. |

| HEPES Buffer | Common pH buffer in cell culture, less temperature-sensitive than bicarbonate. | Used to prepare media with stable pH in non-CO₂ environments, simplifying thermal modeling. |

| Standard Reference Fluids | (e.g., silicone oil, water) For calibrating rheometers and thermal analyzers. | Ensures measurement accuracy, the foundation of reliable CFD input data. |

Within a broader thesis on Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) modeling for local heat transfer coefficient (h) research in pharmaceutical applications, accurate boundary condition (BC) setup is paramount. This protocol details the application of critical BCs—wall functions, thermal boundaries, and inlet/outlet conditions—for simulating equipment such as bioreactors, lyophilizers, vial heating/cooling systems, and mixing vessels. Correct implementation is essential for predicting heat transfer, ensuring sterility, optimizing product quality, and scaling processes from lab to production.

Core Concepts & Quantitative Data

Wall Functions and Near-Wall Treatment

Wall functions bridge the viscous sublayer and the fully turbulent region, preventing prohibitively fine meshes. Selection depends on the non-dimensional wall distance (y+).

Table 1: Wall Function Selection Guide Based on y+

| Target y+ Value | Near-Wall Treatment | Turbulence Model Compatibility | Application in Pharma Equipment |

|---|---|---|---|

| y+ ≈ 1 (Low-Re) | Resolved viscous sublayer (No wall function) | k-ω SST, Low-Re k-ε | Critical heat flux studies, precise shear stress on cells in bioreactors. |

| 5 < y+ < 30 (Buffer) | Enhanced wall treatment | k-ε (Enhanced Wall Function) | General purpose for baffled tanks, jacketed vessel walls. |

| y+ > 30 (High-Re) | Standard wall functions | Standard k-ε, RNG k-ε | Bulk flow in large ductwork, HVAC for cleanrooms. |

Formula for y+: y+ = (y * u_τ) / ν, where y is wall distance, u_τ is friction velocity, ν is kinematic viscosity.

Thermal Boundary Conditions

Thermal BCs define heat interaction at surfaces.

Table 2: Thermal Boundary Condition Types

| BC Type | Mathematical Expression | Pharma Application Example | Key Parameter Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant Wall Temperature | T_wall = Constant | Heated/cooled platen in lyophilizer. | Critical for sublimation rate. |

| Constant Heat Flux | q = -k (∂T/∂n)_wall = Constant | Electric tracing on transfer lines. | Affects local fluid temperature. |

| Convective Heat Flux | q = hamb (Twall - T_amb) | Vial sidewall loss to ambient in a freeze-dryer. | h_amb (external HTC) estimate. |

| Adiabatic (Insulated) | q = 0 | Insulated sections of hot water-for-injection loops. | Assumes perfect insulation. |

Inlet and Outlet Conditions

These define flow entry and exit, crucial for mass/energy balance.

Table 3: Inlet/Outlet Condition Protocols

| Condition Type | Setup Parameters | Stability Consideration | Pharma Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Velocity Inlet | Velocity magnitude, direction, turbulence intensity (~5%), hydraulic diameter. | Suitable for known flow rate. | Feed stream into a bioreactor. |

| Pressure Inlet | Total pressure, turbulence spec., temperature. | For buoyancy-driven or external flows. | Air intake into an isolator. |

| Pressure Outlet | Static (gauge) pressure, backflow conditions. | Must be used with care to avoid reversal. | Exhaust from a drying oven. |

| Outflow (Zero Diffusive Flux) | No pressure specified. | Requires single, fully developed outlet. | Well-developed duct exit. |

Experimental Protocol for Validation

Title: Protocol for Validating CFD Wall Boundary Conditions Using a Heated Pharmaceutical Vessel

Objective: To experimentally measure local wall heat transfer coefficients (h) for validation of CFD BC setup.

Materials & Equipment:

- Bench-scale jacketed glass vessel with controlled jacket fluid inlet temperature (T_j,in).

- Array of calibrated surface thermocouples embedded in vessel wall (T_wall).

- Fluid temperature probes (T_bulk) at multiple axial/radial positions.

- Agitator with torque/RPM control.

- Data acquisition system.

- CFD software (e.g., ANSYS Fluent, OpenFOAM) with prepared mesh.

Procedure:

- System Calibration: Calibrate all temperature and flow sensors. Fill vessel with model fluid (e.g., glycerol-water solution at known viscosity).

- Steady-State Operation: Set jacket circulation to a constant temperature (e.g., 50°C). Set agitator to a fixed RPM (e.g., 100 RPM). Monitor until all temperatures are stable (±0.2°C for 5 minutes).

- Data Acquisition: Record Twall at all sensor locations, Tbulk at positions, T_j,in and outlet, jacket flow rate, and agitator RPM.

- Experimental h Calculation: For each wall sensor location, calculate local hexp using Newton’s law of cooling: q = hexp * (Twall - Tbulk,local). Heat flux (q) is derived from jacket-side energy balance: q = (ṁj * Cp,j * (Tj,in - Tj,out)) / A_local.

- CFD Simulation Setup:

- Mesh: Create mesh with inflation layers to target y+ ~1-5.

- BCs: Set vessel wall with Convective Heat Flux BC, using experimental hexp as an initial guess, or Coupled thermal condition if solving conjugate heat transfer.

- Inlet: Jacket inlet as Velocity Inlet with temperature Tj,in.

- Outlet: Jacket outlet as Pressure Outlet.

- Internal Fluid: Agitated fluid domain with moving reference frame for impeller.

- Validation: Compare simulated local T_wall and fluid temperatures against experimental data. Iteratively refine turbulence model constants and near-wall treatment until error < 10%.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table 4: Essential Materials for CFD Boundary Condition Research in Pharma

| Item / Reagent | Function / Role in Research |

|---|---|

| Glycerol-Water Solutions | Model fluid with tunable viscosity and thermal conductivity for matching Reynolds/Prandtl numbers. |

| Calibrated T-Type Thermocouples | High-accuracy local temperature measurement for BC validation. |

| Heat Flux Sensors (e.g., thin-film) | Direct measurement of surface heat flux for defining/verifying thermal BCs. |

| Laser Doppler Anemometry (LDA) / PIV Systems | Non-intrusive velocity field measurement for validating inlet and near-wall flow profiles. |

| Industrial-Grade Data Logger | Synchronized acquisition of temperature, pressure, and flow rate data. |

| ANSYS Fluent / OpenFOAM License | CFD software platforms for implementing advanced wall functions and BCs. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Enables simulation of high-resolution meshes required for low y+ near-wall resolution. |

Visualization of Methodology

Diagram Title: CFD Boundary Condition Setup & Validation Workflow

Diagram Title: Thermal BC Decision Logic & Data Flow

Within a broader thesis investigating local heat transfer coefficients (h) in bioreactors using Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), the accurate prediction of turbulent flow is paramount. The selection of a turbulence modeling approach—Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS), Large Eddy Simulation (LES), or Direct Numerical Simulation (DNS)—directly dictates the fidelity, computational cost, and practical applicability of the results for bioprocess design, such as optimizing heat exchanger surfaces or ensuring thermal homogeneity for cell culture and drug synthesis.

Table 1: Turbulence Model Comparison for Bioprocess Flows

| Criterion | RANS (k-ε, k-ω SST) | LES | DNS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Models all turbulence scales with time-averaged equations. | Resolves large, energy-containing eddies; models small sub-grid scales. | Resolves all turbulent scales down to the Kolmogorov length. |

| Mesh Resolution (Typical) | Coarse (y+ ~30-300 for wall functions) | Fine (80-90% of turbulent kinetic energy resolved) | Extremely Fine (Δx+ ≈ 5-10 viscous units) |

| Computational Cost | Low (1x baseline) | High (10² - 10⁴ x RANS) | Prohibitive (10⁵ - 10⁷ x RANS) |

| Time Resolution | Steady-state or coarse time steps. | Requires time-accurate simulation with Δt ~ flow time scales. | Requires extremely small time steps (CFL << 1). |

| Typical Application in Bioprocesses | Design screening, steady-state heat transfer, macro-mixing. | Detailed analysis of transient phenomena, shear stress cycles, local h fluctuations. | Fundamental research on turbulence-interface interactions at lab scale. |

| Key Limitation for Heat Transfer | Poor prediction of flow separation and strong streamline curvature; may mispredict local h. | Requires careful near-wall treatment; high cost for high-Re flows. | Computationally impossible for industrial-scale bioreactors. |

Experimental & Numerical Protocols

Protocol 1: Setting Up a RANS Simulation for Bioreactor Heat Transfer Analysis

Objective: To predict the time-averaged local heat transfer coefficient on a fermenter cooling jacket.

Materials/Software: ANSYS Fluent/OpenFOAM, bioreactor CAD geometry, meshing tool (e.g., ANSYS Mesher, snappyHexMesh).

Procedure:

- Geometry & Mesh Preparation:

- Import the 3D bioreactor geometry, including impeller, baffles, and heat transfer surfaces (e.g., jacket, coil).

- Generate a hybrid mesh. Use prism layers near all walls (aim for y+ ~1 for "Enhanced Wall Treatment" or y+ >30 for "Standard Wall Functions"). The core region can use tetrahedral or polyhedral cells.

- Perform mesh independence study using global parameters like torque or overall Nusselt number.

Solver Configuration (in ANSYS Fluent):

- Solver Type: Pressure-Based, Steady or Transient.

- Turbulence Model: Select k-ω SST model for its superior performance in flows with separation and adverse pressure gradients.

- Material Properties: Define fluid (e.g., culture medium) with temperature-dependent viscosity and conductivity.

- Boundary Conditions:

- Walls: Specify wall motion (rotating for impeller), thermal condition (constant heat flux or temperature).

- Inlets/Outlets: Set for sparged gas (if modeled) or closed system.

- Solution Methods: Use SIMPLE/PISO scheme. Use Second-Order Upwind discretization for momentum, turbulence, and energy.

Calculation & Post-Processing:

- Initialize and run calculation until residuals plateau and key monitors stabilize.

- Extract local wall heat flux (q") and local wall (Tw) and fluid bulk temperatures (Tb).

- Calculate local heat transfer coefficient: hlocal = q" / (Tw - Tb). Map hlocal across the heat transfer surface for thesis analysis.

Protocol 2: Conducting an LES for Transient Thermal Loading Studies

Objective: To capture the transient dynamics of thermal streaks and h fluctuations on a microscale cell culture chip substrate.

Materials/Software: High-performance computing cluster, LES-capable code (e.g., OpenFOAM, STAR-CCM+), fine mesh.

Procedure:

- High-Fidelity Mesh Generation:

- Create a fully hex-dominant or structured mesh. The grid must resolve the viscous sublayer (y+ ≈ 1).

- Ensure cell size in all directions is fine enough to capture the inertial subrange (typically Δx+, Δy+, Δz+ < 50).

LES-Specific Setup (in OpenFOAM

pimpleFoam):- Sub-Grid Scale (SGS) Model: Choose the Dynamic Smagorinsky-Lilly model.

- Temporal Discretization: Use a second-order implicit scheme with a very small time step to achieve a Courant number < 1.

- Boundary Conditions: Use synthetic or precursor turbulent inflow conditions. Set convective outflow.

Run & Advanced Analysis:

- Run the simulation for a significant flow-through time to establish developed turbulence.

- Sample data over several integral time scales for statistical convergence.

- Analyze the instantaneous and time-averaged h fields. Calculate turbulence statistics (e.g., RMS of h fluctuations) crucial for understanding thermal stress on sensitive biologics.

Visualizations

Diagram Title: Turbulence Model Selection Logic for Heat Transfer CFD

Diagram Title: General CFD Protocol for Local h Research