Electrochemical vs. Traditional Synthesis: A Comparative Analysis for Sustainable Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of electrochemical and traditional organic synthesis methods, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development.

Electrochemical vs. Traditional Synthesis: A Comparative Analysis for Sustainable Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of electrochemical and traditional organic synthesis methods, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development. It explores the foundational principles of green chemistry that underpin modern electrochemical techniques and contrasts them with conventional approaches. The scope spans methodological innovations, practical applications in synthesizing active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), troubleshooting for scalability and optimization, and a rigorous validation of the environmental and economic advantages of electrochemistry. By synthesizing recent advancements and current challenges, this review aims to serve as a strategic guide for adopting more efficient and sustainable synthetic pathways in pharmaceutical research.

Green Chemistry Foundations: Principles Driving Sustainable Synthesis

The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry as a Framework for Evaluation

The global chemical industry stands at a pivotal juncture, facing increasing regulatory pressure and societal demand for more sustainable manufacturing practices. Within this context, green chemistry principles provide a systematic framework for evaluating the environmental and economic merits of chemical processes [1]. This review applies this framework to conduct a comparative analysis of emerging electrochemical synthesis methods against established traditional synthesis pathways. The pharmaceutical and specialty chemical industries, in particular, represent critical test cases where efficiency, selectivity, and waste reduction are paramount concerns [2] [3].

Traditional chemical manufacturing has historically generated substantial waste, with the pharmaceutical sector often exhibiting E-factors (kg waste/kg product) exceeding 100 [3]. The twelve principles of green chemistry, first articulated by Anastas and Warner in 1998, provide a comprehensive methodology for addressing these inefficiencies [1]. These principles emphasize waste prevention, atom economy, reduced hazard, and energy efficiency—metrics that collectively enable objective comparison of competing synthetic technologies [2] [3].

Electrochemical synthesis represents a promising alternative approach that utilizes electrons as traceless reagents to drive redox transformations [4]. This methodology replaces traditional chemical oxidants and reductants, potentially eliminating associated waste streams while enabling unique reaction pathways inaccessible through conventional methods. The following analysis employs the green chemistry framework to evaluate both techniques across theoretical and operational dimensions, providing researchers with evidence-based guidance for sustainable process design.

Comparative Analysis Using Green Chemistry Principles

The twelve principles of green chemistry provide a systematic framework for evaluating the environmental and economic merits of chemical processes. The table below presents a comparative analysis of electrochemical versus traditional synthesis methods against these principles.

Table 1: Evaluation of Synthesis Methods Against Green Chemistry Principles

| Green Chemistry Principle | Traditional Synthesis | Electrochemical Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Waste Prevention | High waste (E-factors 25-100 in pharma); E-factor often >100 [3] | Prevents waste via electron transfer; E-factor <5 target [4] [3] |

| 2. Atom Economy | Variable; often requires stoichiometric oxidants/reductants [1] | inherently high; electrons as traceless reagent [4] |

| 3. Less Hazardous Synthesis | Often uses toxic reagents (e.g., phosgene, cyanides) [5] | Reduces hazardous reagents; enables milder pathways [4] [3] |

| 4. Designing Safer Chemicals | Post-hoc modification often needed [1] | Inherently safer process conditions [3] |

| 5. Safer Solvents & Auxiliaries | Often uses hazardous solvents (e.g., DMF, dioxane) [2] | Compatible with green solvents (e.g., water, ethanol) [4] [6] |

| 6. Energy Efficiency | Often requires high T/P; energy-intensive [3] | Can proceed at ambient T/P; energy efficient [4] [3] |

| 7. Renewable Feedstocks | Primarily petroleum-based [3] | Compatible with biomass-derived feedstocks [4] |

| 8. Reduce Derivatives | Often requires protecting groups [1] | High selectivity can avoid protecting groups [4] |

| 9. Catalysis | Stoichiometric reagents common [3] | Electron transfer is catalytic; electrocatalyst development [4] |

| 10. Design for Degradation | Product-focused, not process-focused [1] | Process improves product lifecycle profile [3] |

| 11. Real-time Analysis | Challenging and costly to implement [1] | Inherently enables real-time monitoring [4] |

| 12. Inherently Safer Chemistry | Often uses hazardous conditions [3] | Accident prevention via controlled potential/current [4] |

The quantitative comparison reveals fundamental advantages in electrochemical methods across multiple green chemistry principles. The most significant differentiators include waste prevention (Principle 1), where electrochemical processes eliminate stoichiometric oxidants and reductants, substantially reducing E-factors [3]. In energy efficiency (Principle 6), electrochemical reactions frequently proceed under ambient temperature and pressure conditions, contrasting with the energy-intensive high-temperature and high-pressure requirements of many traditional pathways [4]. Additionally, hazard reduction (Principles 3, 4, 5) is enhanced through the elimination of toxic reagents and the compatibility with aqueous reaction media [6] [5].

Atom Economy and Waste Prevention

Atom economy, a cornerstone metric of green chemistry, demonstrates fundamental differences between these approaches. Traditional synthesis frequently employs stoichiometric quantities of oxidizing or reducing agents whose atoms are not incorporated into the final product, resulting in inherent atom inefficiency [1]. In contrast, electrochemical synthesis utilizes electrons as "traceless reagents" that drive redox reactions without generating stoichiometric byproduct waste [4].

The environmental factor (E-factor) provides a complementary metric, quantifying total waste generated per unit of product. Pharmaceutical manufacturing using traditional methods typically exhibits E-factors between 25-100, meaning 25-100 kg of waste are generated for each kg of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) produced [3]. Early adoption of electrochemical methods demonstrates substantially improved E-factors, with targets below 5 for specialty chemicals and potentially lower for optimized processes [3]. This dramatic reduction stems primarily from eliminating stoichiometric reagents and simplifying purification processes through enhanced selectivity.

Energy Efficiency and Reaction Conditions

Energy consumption represents another critical differentiator. Traditional synthesis often requires energy-intensive conditions including high temperatures, elevated pressures, and extended reaction times [3]. These requirements contribute significantly to the carbon footprint of chemical manufacturing. Electrochemical synthesis can proceed efficiently at ambient temperature and pressure, substantially reducing energy inputs [4]. Furthermore, the integration of renewable electricity sources enables decarbonization of the energy input itself, creating pathways toward carbon-neutral chemical production [7].

Recent technological innovations have further enhanced the energy efficiency of electrochemical synthesis. The development of light-activated microdevices such as the SPECS (Small Photoelectronics for ElectroChemical Synthesis) platform demonstrates the potential for wireless electrochemical synthesis driven by light energy [6]. This 2mm device functions as a miniature solar panel, generating sufficient current to drive electrochemical reactions in high-throughput experiment plates without external wiring or traditional power supplies [6].

Experimental Comparison: Selected Case Studies

Pharmaceutical Intermediate Synthesis

The synthesis of Sitagliptin (Januvia) exemplifies the green chemistry advantages of electrochemical and biocatalytic routes over traditional synthesis. Merck developed a transaminase enzyme producing the chiral amine building block, replacing a rhodium-catalyzed hydrogenation requiring high pressure [3].

Table 2: Comparative Experimental Data for Sitagliptin Synthesis

| Parameter | Traditional Rh-Catalyzed Route | Green Biocatalytic/Electrochemical Route |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyst | Rhodium (precious metal) | Transaminase enzyme |

| Conditions | High-pressure H₂ | Ambient pressure |

| Waste Reduction | Baseline | 19% reduction |

| Step Count | Multiple steps | Streamlined process |

| Hazard Profile | Genotoxic intermediate | Eliminated genotoxic intermediate |

The green route reduced waste by 19% while eliminating a genotoxic intermediate [3]. This case demonstrates how biocatalysis exemplifies multiple green chemistry principles simultaneously, including energy efficiency (Principle 6, through ambient temperature operation), safer solvents (Principle 5, using aqueous environments), and reduced derivatives (Principle 8, through high enzymatic specificity) [3].

Fine Chemical Production

The synthesis of p-anisaldehyde provides a compelling case study comparing traditional chemical oxidation with electrochemical alternatives. This high-value fragrance and flavor compound has been produced through various routes with dramatically different environmental profiles.

Table 3: Experimental Comparison of p-Anisaldehyde Synthesis Methods

| Method | Oxidant/Reductant | Solvent | Temperature | Yield | E-factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chromium-based | CrO₃ (stoichiometric) | Organic solvents | 60-80°C | 75-85% | ~35 |

| Manganese-based Oxidation | MnO₂ (stoichiometric) | Dichloromethane | Reflux | 70-80% | ~28 |

| Electrochemical Synthesis | Electrons (traceless) | Methanol/Water | 25°C | 88% | ~5 |

The electrochemical route eliminates hazardous heavy metals like chromium and manganese, whose disposal represents significant environmental liabilities [4]. Additionally, it replaces dichloromethane—a hazardous air pollutant and suspected carcinogen—with a greener methanol-water mixture [5]. The combination of ambient temperature operation and aqueous solvent systems reduces energy consumption by 60-80% compared to traditional thermal routes [3].

Methodology for Comparative Evaluation

Experimental Protocols for Method Assessment

Protocol 1: Electrochemical Synthesis of Aldehydes from Alcohols

- Reaction Setup: Utilize an undivided electrochemical cell equipped with a boron-doped diamond (BDD) anode and stainless steel cathode [4]. The electrolyte consists of 0.1 M Na₂CO₃ in 20:1 methanol-water. Substrate (alcohol) concentration: 10 mM.

- Electrolysis Conditions: Constant current electrolysis at 10 mA/cm² current density, ambient temperature (25°C), under air atmosphere. Reaction monitoring via in-line UV-Vis spectroscopy or periodic HPLC sampling [4].

- Workup & Analysis: Upon reaction completion (typically 2-4 hours), evaporate solvent under reduced pressure. Purify the residue via flash chromatography (silica gel, ethyl acetate/hexane gradient). Analyze product structure and purity by ( ^1H ) NMR, GC-MS, and HPLC against authentic standards.

- Green Metrics Calculation: Determine atom economy from reaction stoichiometry. Calculate E-factor by measuring all inputs (substrates, solvents, electrolytes) and outputs (product, recovered materials). Process Mass Intensity (PMI) includes all inputs (solvents, electrolytes) per product mass [3].

Protocol 2: Traditional Chemical Oxidation of Alcohols to Aldehydes

- Reaction Setup: Use a round-bottom flask equipped with stir bar, reflux condenser, and heating mantle. Employ pyridinium chlorochromate (PCC) as oxidant (1.5 equiv) in anhydrous dichloromethane (DCM) [5].

- Reaction Conditions: Add alcohol substrate (1.0 equiv) to PCC suspension in DCM at room temperature. Stir for 1-2 hours under nitrogen atmosphere. Monitor reaction progress by TLC.

- Workup & Analysis: Filter the reaction mixture through a pad of silica gel to remove chromium salts. Wash filter cake extensively with diethyl ether. Concentrate filtrate under reduced pressure. Purify crude product via flash chromatography.

- Green Metrics Calculation: Quantify all materials including stoichiometric oxidant, solvents for reaction and purification, and filter aids. Measure hazardous waste (chromium-containing residues) separately for proper disposal cost accounting [3].

Analytical Methods for Green Metrics Calculation

Atom Economy Calculation: [ \text{Atom Economy} = \frac{\text{Molecular Weight of Product}}{\text{Molecular Weight of All Reactants}} \times 100\% ]

For electrochemical reactions where electrons are the only "reagent," atom economy approaches 100% as no reactant atoms are incorporated into waste streams [4].

Environmental Factor (E-Factor) Calculation: [ \text{E-Factor} = \frac{\text{Total Mass of Waste (kg)}}{\text{Mass of Product (kg)}} ]

Process Mass Intensity (PMI): [ \text{PMI} = \frac{\text{Total Mass Used in Process (kg)}}{\text{Mass of Product (kg)}} ]

PMI provides a more comprehensive assessment than E-factor by accounting for all mass inputs including solvents, water, and consumables [3].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The successful implementation of electrochemical synthesis requires specialized materials and reagents that differ from traditional organic synthesis. The table below details key components for establishing electrochemical synthesis capabilities.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Electrochemical Synthesis

| Item | Function/Description | Green Chemistry Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Boron-Doped Diamond (BDD) Electrode | Anode material with wide potential window [4] | Enables unique reaction pathways; high durability |

| Carbon-based Electrodes (Graphite, Glassy Carbon) | Versatile cathode/anode materials [4] | Low cost, good conductivity, variety of forms |

| Ionic Liquids | Potential electrolytes and/or solvents [4] | Low volatility, tunable properties, recyclable |

| Green Solvents (Water, EtOH) | Reaction media [6] | Renewable, low toxicity, reduced VOC emissions |

| Solid-supported Catalysts | Heterogeneous electrocatalysts [4] | Recyclability, simplified product isolation |

| SPECS Device | Wireless, light-activated micro photodiode array [6] | Enables high-throughput electrochemistry without complex wiring |

| Supporting Electrolytes (e.g., LiClO₄) | Provide conductivity in organic solvents [4] | Essential for non-aqueous electrochemistry |

The selection of electrode materials represents a critical consideration, influencing reaction efficiency, selectivity, and scalability. Boron-doped diamond electrodes provide an exceptionally wide potential window, enabling transformations inaccessible with conventional metal electrodes [4]. The emergence of wireless electrochemical devices like SPECS demonstrates how technological innovation can dramatically simplify experimental setup, making electrochemical methods more accessible to synthetic chemists [6].

Market Adoption and Implementation Challenges

The electrochemical transformation market is projected to grow from $1.7 billion in 2024 to $4.1 billion by 2034, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 9.3% [7]. This growth trajectory significantly outpaces the overall chemical market, indicating rapid technology adoption. The pharmaceutical industry represents the largest application segment, exceeding 40% market share, driven by needs for efficient and sustainable API synthesis [8].

Despite compelling advantages, several implementation challenges hinder broader adoption. High initial investment requirements for specialized equipment present barriers, particularly for small and medium enterprises [8]. Additionally, technical expertise gaps exist between traditional synthetic organic chemists and electrochemical methods, creating workforce training needs [4]. Furthermore, scalability challenges persist in translating laboratory-scale electrochemical reactions to industrial production, though continuous flow reactors are increasingly addressing this limitation [4] [8].

Table 5: Market Adoption Metrics for Electrochemical Synthesis

| Metric | Current Status (2024-2025) | Projected Growth |

|---|---|---|

| Global Market Size | $1.7 - 2.0 billion [8] [7] | $4.1 billion by 2034 (CAGR 9.3%) [7] |

| Pharmaceutical Segment Share | >40% [8] | Increasing with API demand |

| U.S. Market Size | Projected to exceed $940 million by 2034 [7] | |

| Electrochemical Reduction Segment | Projected to exceed $1.4 billion by 2034 [7] |

Regulatory drivers including the European Union's Green Deal Industrial Plan and Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism are accelerating adoption by making traditional chemical manufacturing increasingly costly from an environmental compliance perspective [7]. Similarly, the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act includes approximately $6 billion to support deployment of low-carbon industrial technologies, including electrochemical processes [7].

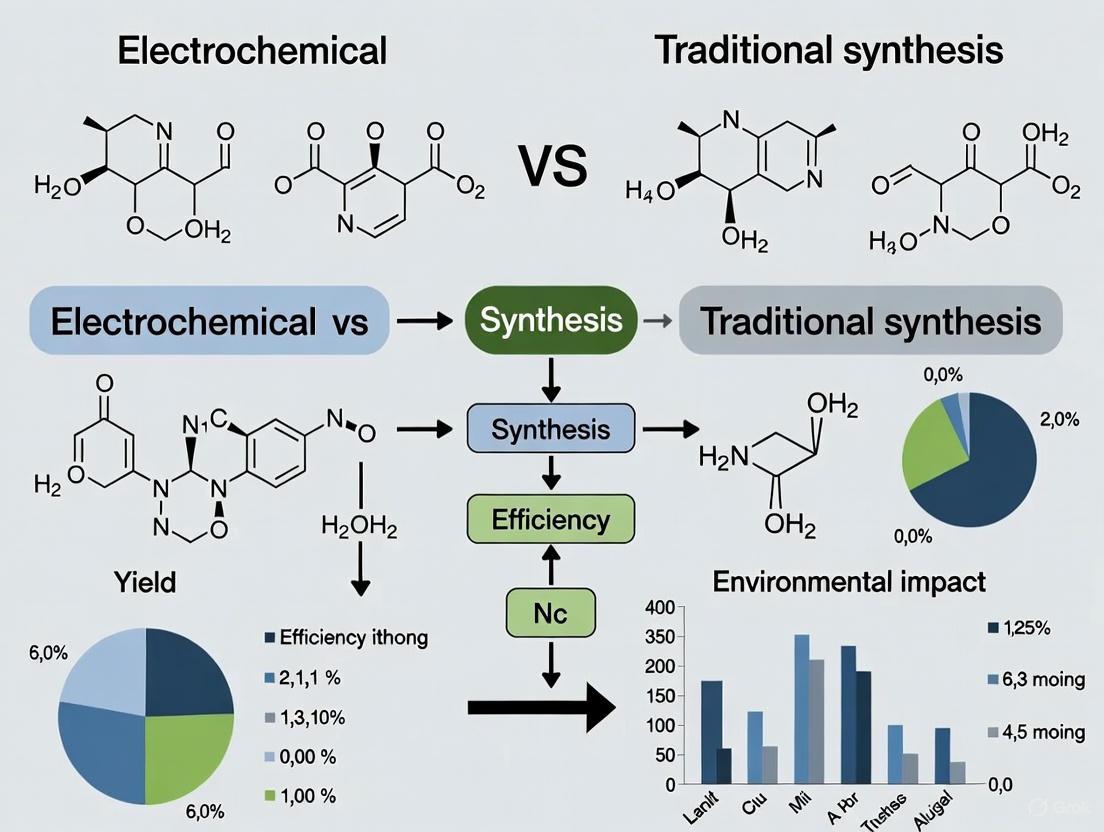

Visualizing the Experimental Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the comparative experimental workflow for evaluating synthesis methods using green chemistry principles, highlighting key decision points and assessment metrics.

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for Green Chemistry Evaluation

This workflow enables systematic comparison between traditional and electrochemical approaches, guiding researchers toward more sustainable synthetic planning. The evaluation phase incorporates quantitative green metrics that provide objective data for decision-making [3].

The systematic application of the twelve principles of green chemistry provides an unambiguous framework for evaluating synthetic methodologies. This comparative analysis demonstrates that electrochemical synthesis offers significant advantages across multiple green principles, particularly in waste prevention, atom economy, energy efficiency, and hazard reduction [4] [3]. The case studies examining pharmaceutical intermediates and fine chemicals provide experimental validation of these advantages, with demonstrated reductions in E-factors, elimination of hazardous reagents, and improved reaction conditions.

Despite implementation challenges including initial investment requirements and technical training needs, the compelling environmental and economic benefits are driving rapid market adoption [8] [7]. The projected growth of the electrochemical transformation market to $4.1 billion by 2034 reflects increasing recognition of these advantages across the chemical industry [7]. Ongoing technological innovations—such as wireless electrochemical devices, advanced electrode materials, and continuous flow reactors—are progressively addressing implementation barriers [4] [6].

For researchers and drug development professionals, the integration of electrochemical methods represents both an opportunity and imperative. As regulatory pressure increases and sustainability metrics become integral to process evaluation, electrochemical synthesis will increasingly displace traditional approaches. The framework presented herein provides both theoretical foundation and practical methodology for conducting these evaluations, supporting the chemical industry's transition toward more sustainable manufacturing paradigms.

Traditional chemical synthesis has long relied on a well-established paradigm of using stoichiometric quantities of chemical reagents to drive molecular transformations. This approach, developed over centuries, forms the backbone of modern chemical manufacturing, particularly in the pharmaceutical and specialty chemicals industries. However, this methodology carries significant environmental implications due to its inherent dependency on hazardous materials and waste-generating processes. The foundational principles of traditional synthesis often prioritize reaction yield and speed over environmental considerations, leading to processes where the environmental factor (E-factor) – a measure of waste generated per unit of product – can exceed 100 in pharmaceutical manufacturing. This means producing one kilogram of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) can generate over 100 kilograms of waste [3].

A coherent framework for evaluating the environmental impact of chemical processes was established more than two decades ago with the formulation of the 12 principles of green chemistry [2]. These principles provide a critical lens through which traditional synthesis can be assessed and improved. They emphasize waste prevention, atom economy, the use of less hazardous substances, and energy efficiency, among other factors. When measured against these principles, traditional synthesis reveals several systemic shortcomings, particularly in its reliance on hazardous reagents and energy-intensive conditions that contribute substantially to environmental pollution and resource depletion [2] [3].

Core Characteristics and Reagents of Traditional Synthesis

Fundamental Principles and Common Reagents

Traditional synthesis is characterized by its reliance on stoichiometric reagents, high energy inputs, and sequential reaction steps that often necessitate purification between stages. The atom economy – a concept that measures the proportion of reactant atoms incorporated into the final desired product – is frequently poor in traditional approaches [2]. This inefficiency stems from the use of protecting groups, derivatization, and stoichiometric reagents that ultimately become waste.

Common reagent classes in traditional synthesis include:

- Stoichiometric oxidizing agents such as chromium(VI) oxides, permanganates, and peroxides

- Stoichiometric reducing agents including metal hydrides (e.g., lithium aluminum hydride, sodium borohydride)

- Coupling reagents for amide and peptide bond formation that generate stoichiometric byproducts

- Heavy metal catalysts containing palladium, nickel, or copper that can leave toxic residues

- Corrosive acids and bases for hydrolysis, condensation, and other fundamental transformations

These reagents are often employed in organic solvents – particularly petroleum-derived solvents like dimethylformamide (DMF), tetrahydrofuran (THF), and dichloromethane – which account for approximately 85% of the mass of waste in pharmaceutical manufacturing [3]. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has estimated that solvent emissions from chemical manufacturing accounted for up to 62% of total emissions in 2017 [9].

Environmental Impact and Waste Generation

The environmental impact of traditional synthesis extends across the entire chemical lifecycle, from resource extraction to waste disposal. Key environmental concerns include:

- High E-factors: Traditional pharmaceutical manufacturing typically generates 25-100 kg of waste per kg of product, significantly higher than most other chemical industries [3].

- Resource depletion: Dependence on petroleum-derived solvents and feedstocks contributes to fossil fuel depletion.

- Toxic waste streams: Heavy metal contaminants and persistent organic pollutants can accumulate in ecosystems.

- Energy intensity: Many traditional processes require high temperatures and pressures, contributing to substantial greenhouse gas emissions.

The Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reaction exemplifies these challenges. While immensely valuable for forming carbon-carbon bonds, traditional protocols require unfavorable solvents like 1,4-dioxane and DMF, along with palladium catalysts that necessitate careful disposal due to their environmental persistence [2]. Similarly, reductive amination – used in approximately 25% of carbon-nitrogen bond formations in pharmaceutical manufacturing – traditionally employs stoichiometric hydride reagents or gaseous hydrogen under pressure, generating significant waste and requiring specialized infrastructure [9].

Quantitative Comparison: Traditional vs. Electrochemical Synthesis

Performance Metrics and Environmental Indicators

The differences between traditional and electrochemical synthesis become particularly evident when examining quantitative metrics for specific chemical transformations. The following table compares key performance indicators for both approaches:

Table 1: Comparative Metrics for Traditional vs. Electrochemical Synthesis

| Parameter | Traditional Synthesis | Electrochemical Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Typical E-factor | 25-100+ (pharmaceuticals) [3] | Significantly reduced (5-20 target) [3] |

| Atom Economy | Often low due to derivatization [2] | Inherently higher, electrons are traceless [4] |

| Energy Consumption | High (frequent heating/cooling) [3] | Moderate (often ambient conditions) [4] |

| Redox Reagents | Stoichiometric quantities required [9] | Electrons as clean reagents [10] |

| Solvent Intensity | High (often >10 L/kg product) [3] | Variable (aqueous systems possible) [9] |

| Waste Generation | Significant (reagents, solvents, byproducts) [2] | Drastically reduced [9] |

| Temperature Requirements | Often elevated (50-150°C) [3] | Frequently ambient [4] |

Case Study: Reductive Amination

The quantitative advantages of electrochemical methods are clearly demonstrated in the transformation of reductive amination. Recent research has developed an electrochemical reductive amination (ERA) protocol employing an acetonitrile-water azeotrope as a recoverable reaction medium, enabling efficient management of solvents and electrolytes [9]. The experimental protocol and results highlight the stark contrasts between approaches:

Table 2: Experimental Comparison for Reductive Amination

| Aspect | Traditional Approach | Electrochemical Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Reducing Agent | NaBH₄, NaBH₃CN, or H₂ gas [9] | Electrons (direct reduction at cathode) [9] |

| Reaction Medium | Often methanol, ethanol, or THF [9] | Recoverable MeCN:H₂O azeotrope [9] |

| Catalyst Requirements | Sometimes required with H₂ gas | Graphite cathode, aluminum anode [9] |

| Workup | Quenching, extraction, purification | Simplified isolation [9] |

| Waste Streams | Metal borides, solvent waste | Minimal, recoverable medium [9] |

| Environmental Assessment | High Process Mass Intensity | Significantly improved metrics [9] |

The electrochemical protocol was optimized through systematic investigation of solvent systems, electrode materials, and supporting electrolytes. The use of a recoverable reaction medium – specifically an acetonitrile-water azeotrope – proved crucial for minimizing waste while maintaining high conductivity for the electrochemical process [9]. This approach exemplifies how electrochemical methods can align with multiple green chemistry principles, particularly waste prevention, use of safer solvents, and design for energy efficiency.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Traditional Reductive Amination Protocol

A representative traditional method for reductive amination follows this detailed procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Dissolve the carbonyl compound (1.0 mmol) and amine (1.2-1.5 mmol) in anhydrous methanol (10 mL) in a round-bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar.

- Imine Formation: Stir the reaction mixture at room temperature for 1-2 hours to pre-form the imine intermediate. Reaction progress can be monitored by TLC or GC-MS.

- Reduction: Cool the reaction mixture to 0°C in an ice bath. Slowly add sodium cyanoborohydride (1.5 mmol) portionwise over 5-10 minutes. Caution: Hydrogen cyanide gas may be liberated during this step.

- Acidification: After complete addition, carefully acidify the reaction mixture to pH 3-4 using 1M HCl.

- Stirring: Allow the reaction to warm to room temperature and stir for an additional 4-12 hours.

- Workup: Carefully basify the reaction mixture to pH 10-11 using 1M NaOH. Extract the product with dichloromethane (3 × 15 mL).

- Purification: Combine the organic extracts, dry over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, filter, and concentrate under reduced pressure.

- Further Purification: Purify the crude product by flash column chromatography if necessary.

This procedure typically yields the desired amine product but generates significant waste including metal-containing byproducts, solvent waste from extraction and chromatography, and potential gaseous hazards [9].

Electrochemical Reductive Amination Protocol

The waste-minimized electrochemical reductive amination protocol follows this alternative methodology:

- Electrochemical Cell Setup: Utilize an undivided electrochemical cell equipped with a graphite cathode and aluminum anode (both 1 cm × 2 cm), connected to a DC power supply [9].

- Reaction Mixture Preparation: Combine the carbonyl compound (0.5 mmol), amine (0.5 mmol), and tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate (0.5 mmol) as supporting electrolyte in a recoverable acetonitrile-water azeotrope (5 mL, 16% w/w water) [9].

- Electrolysis: Conduct the electrolysis at a constant current of 20 mA at room temperature for 120 minutes, passing a total charge of 3 F mol⁻¹.

- Reaction Monitoring: Monitor reaction progress by analytical methods (GLC or LC-MS).

- Product Isolation: After completion, concentrate the reaction mixture under reduced pressure. The acetonitrile-water azeotrope can be recovered by distillation during this process.

- Purification: Purify the residue by flash chromatography or recrystallization if necessary.

This electrochemical protocol eliminates the need for stoichiometric hydride reagents, simplifies the workup procedure, and allows for recovery and reuse of the reaction medium, significantly reducing the environmental footprint of the transformation [9].

Visualization of Synthesis Pathways and Impacts

Synthesis Workflow Comparison

The fundamental differences between traditional and electrochemical synthesis approaches can be visualized through their respective workflows:

Diagram 1: Synthesis Workflow Comparison

Environmental Impact Pathway

The environmental implications of traditional synthesis follow a distinct pathway that can be visualized as:

Diagram 2: Environmental Impact Pathway of Traditional Synthesis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Traditional Synthesis Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents in Traditional Synthesis

| Reagent/Solution | Primary Function | Environmental Concerns |

|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Oxidants (e.g., KMnO₄, CrO₃) | Selective oxidation of functional groups | Heavy metal contamination, toxic byproducts |

| Stoichiometric Reductants (e.g., LiAlH₄, NaBH₄) | Reduction of carbonyls, imines | Reactive waste, hydrogen gas evolution |

| Palladium Catalysts (e.g., Pd(PPh₃)₄) | Cross-coupling reactions | Heavy metal residue, cost, and scarcity |

| Petroleum-Derived Solvents (e.g., DMF, THF) | Reaction medium, solubility | VOC emissions, petrochemical dependency |

| Activating Agents (e.g., DCC, HATU) | Peptide coupling, esterification | Stoichiometric byproducts, waste generation |

| Strong Acids/Bases (e.g., H₂SO₄, NaOH) | Catalysis, hydrolysis, pH adjustment | Corrosive waste, neutralization requirements |

Electrochemical Synthesis Materials

Table 4: Essential Components in Electrochemical Synthesis

| Component | Primary Function | Environmental Advantages |

|---|---|---|

| Electrode Materials (e.g., graphite, BDD) | Electron transfer interface | Reusable, minimal consumption |

| Supporting Electrolytes (e.g., Bu₄NPF₆) | Conductivity enhancement | Often recyclable, minimal quantities |

| Green Solvent Systems (e.g., MeCN:H₂O azeotrope) | Reaction medium | Recoverable, reduced VOC emissions |

| DC Power Supply | Controlled electron delivery | Renewable energy compatible |

| Electrochemical Cells (divided/undivided) | Reaction containment | Enables ambient condition reactions |

| Ion-Exchange Membranes (in divided cells) | Compartment separation | Enables selective transformations |

The comparative analysis between traditional and electrochemical synthesis methods reveals a clear paradigm shift in sustainable chemical production. Traditional synthesis, characterized by its dependence on stoichiometric reagents, hazardous solvents, and energy-intensive conditions, generates substantial waste and environmental impact as quantified by high E-factors and poor atom economy. In contrast, electrochemical synthesis leverages electrons as traceless reagents, operates frequently under milder conditions, and offers pathways to significantly reduce the environmental footprint of chemical transformations.

The case study on reductive amination demonstrates that electrochemical approaches can maintain synthetic efficiency while addressing fundamental green chemistry principles. The development of recoverable reaction media, inexpensive electrode materials, and simplified workup procedures positions electrochemical synthesis as a transformative technology for the pharmaceutical and specialty chemical industries. As regulatory pressures increase and the demand for sustainable manufacturing grows, electrochemical methods represent not merely an alternative but a necessary evolution in chemical synthesis that aligns economic objectives with environmental responsibility.

Electrochemical synthesis is undergoing a significant renaissance as a sustainable platform for chemical production, particularly in the pharmaceutical and fine chemicals industries. This method utilizes electricity as a clean reagent to drive redox reactions, offering a compelling alternative to traditional synthetic pathways that often rely on stoichiometric quantities of hazardous and wasteful chemical oxidants and reductants. This guide provides an objective comparison of electrochemical and traditional synthesis methods, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, to inform researchers and drug development professionals in their methodological selection.

Principles and Comparative Advantages

Electrochemical synthesis facilitates chemical transformations through electron transfer at the surfaces of electrodes (anode and cathode), effectively using electrons as a traceless reagent [10]. This core principle underlies several key advantages when compared to traditional chemical synthesis.

The following table summarizes the fundamental differences between the two approaches:

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Synthesis Methods

| Feature | Electrochemical Synthesis | Traditional Chemical Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Redox Agent | Electrons (electric current) [11] | Stoichiometric chemical oxidants/reductants [11] |

| Byproduct | Often hydrogen gas (in cross-coupling) [11] | Chemical waste from spent oxidants/reductants [11] |

| Reaction Control | Precision via applied potential/current [11] | Limited by reagent strength and properties |

| Functional Group Tolerance | Typically high [11] | Can be low, depending on reagents used |

| Reaction Conditions | Often mild temperature and pressure [11] | Frequently requires elevated temperature/pressure [11] |

| Process Stopping | Instantaneous (switch off power) [11] | Requires quenching, which can be complex [11] |

A primary green advantage of electrosynthesis is the avoidance of stoichiometric oxidants and reductants. For instance, in C-H amination reactions, traditional methods often require multiple equivalents of silver nitrate (AgNO₃) as an oxidant, generating substantial metal waste. Electrochemical methods can achieve the same transformation using renewable electricity, with the cobalt catalyst being recycled by anodic oxidation, thereby offering a cleaner protocol [11].

Furthermore, electrochemical oxidative cross-coupling between two C-H bonds (R₁-H/R₂-H) is a highly atom-economical strategy. This reaction produces the desired cross-coupling product and valuable hydrogen gas as the only by-product, operating under essentially waste-free conditions. In contrast, traditional oxidative coupling methods typically generate large quantities of undesired waste [11].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

To objectively evaluate the practical impact of these principles, it is crucial to examine performance data across key metrics such as energy consumption, yield, and environmental footprint.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Select Syntheses

| Product/Target | Method | Key Metric | Result | Experimental Conditions & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C–H Amination | Traditional Chemical | AgNO₃ Oxidant Used | 2.5 equivalents [11] | Generates stoichiometric silver waste [11]. |

| C–H Amination | Electrochemical | Oxidant Used | None (electricity only) [11] | Cobalt catalyst recycled at anode; process in renewable solvent (tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-one) [11]. |

| Bismuth Basic Nitrates (BBNs) | Electrochemical | Sorption Efficiency (RB19 Dye) | Up to 98.34% [12] | Efficiency dependent on electrodeposition current density; higher density (200 mA cm⁻²) favored BBN formation and performance [12]. |

| Adiponitrile (Industrial Scale) | Traditional Chemical | Energy Consumption | Higher | Requires high temperature and pressure [13]. |

| Adiponitrile (Monsanto Process) | Electrochemical | Energy Consumption | Lower | A industrialized example demonstrating energy efficiency and scalability [14]. |

| General Fine Chemicals | Electrochemical | Energy Efficiency | Attractive | Conversion of fine chemicals is more energy-efficient than electrochemical generation of synthetic fuels [13]. |

Experimental Protocols in Practice

To illustrate the implementation of these principles, here are detailed methodologies for key electrochemical reactions cited in the literature.

Protocol: Electrochemical C–H Amination

This protocol, adapted from published work, describes an exogenous-oxidant-free amination [11].

- Reaction Setup: An undivided electrochemical cell is equipped with a platinum plate cathode and a carbon rod anode.

- Electrolyte and Solvent: The reaction uses tetrabutylammonium acetate as the electrolyte (c. 20 mol%) in tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-one as a renewable solvent.

- Substrates: Aromatic amides and cyclic secondary amines are used as starting materials.

- Reaction Procedure: The reactants and electrolyte are dissolved in the solvent in the electrochemical cell. A constant current is applied, and the reaction is stirred at room temperature until completion, monitored by TLC or LC-MS.

- Work-up: After turning off the power, the reaction mixture is diluted with water and extracted with an organic solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate). The combined organic layers are concentrated, and the product is purified by chromatography.

- Key Insight: The acetate electrolyte facilitates deprotonation, and the resultant N-anion is oxidized at the anode to generate a N-centered radical, which propagates the reaction. Hydrogen gas is evolved at the cathode [11].

Protocol: Paired Electrosynthesis for Oxindole Synthesis

This protocol highlights the efficiency of paired electrolysis, where both half-reactions are synthetically useful [10] [14].

- Reaction Setup: An undivided cell is fitted with inert electrodes.

- Catalyst: A catalytic amount of ferrocene (Cp₂Fe) is used as a redox mediator.

- Substrate: An N-aryl acrylamide substrate is used.

- Reaction Mechanism: The mechanism involves anodic oxidation of the ferrocene catalyst, which then mediates the intramolecular cross-coupling of C(sp³)–H and C(sp²)–H bonds in the substrate to form the oxindole cycle. The corresponding cathodic reaction is utilized productively.

- Outcome: This method provides a highly efficient route to a family of oxindole compounds without the need for stoichiometric external oxidants [10].

Workflow and System Visualization

The following diagrams illustrate the logical and operational concepts central to electrochemical synthesis.

Paired Electrolysis Concept

Basic Electrosynthesis Setup

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimental execution in electrochemical synthesis requires specific materials and reagents, each fulfilling a critical function.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Electrosynthesis

| Item | Function/Purpose | Common Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Electrode Materials | Surface for electron transfer; critical for reaction selectivity and stability. | Anode: Carbon rods, platinum, boron-doped diamond (BDD).Cathode: Platinum plate, carbon, stainless steel [11] [10]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Conducts current within the solution; enables electron transfer between electrodes. | Tetrabutylammonium salts (e.g., tetrabutylammonium acetate), lithium perchlorate. Must be soluble and electrochemically stable in the chosen solvent [11] [10]. |

| Solvent | Dissolves substrates, electrolyte, and other reagents. | Acetonitrile, DMF, methanol, and renewable solvents like tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-one. Solvent choice is limited by conductivity [11]. |

| Redox Mediators / Catalysts | Shuttles electrons between electrode and substrate; lowers overpotential, enables new reactions. | Ferrocene (Cp₂Fe), cobalt complexes, TEMPO. Often used in catalytic quantities [10] [14]. |

| Electrochemical Cell | Vessel containing the reaction mixture and electrodes. | Divided cell (separates anode/cathode chambers with membrane) or undivided cell (simpler, but requires compatible half-reactions) [11] [14]. |

The direct comparison presented in this guide demonstrates that electrochemical synthesis provides a fundamentally greener and often more efficient pathway for a range of chemical transformations. The use of electricity as a clean reagent eliminates the generation of significant stoichiometric waste, a major drawback of traditional methods. While challenges such as the initial cost of equipment and the need for specialized optimization remain, the benefits in terms of sustainability, energy efficiency, and unique reactivity are driving its adoption in modern labs and industry. For researchers in drug development, mastering these electrochemical tools and principles is becoming increasingly crucial for developing more sustainable and cost-effective synthetic routes.

Atom Economy and Waste Prevention in Redox Reactions

Atom Economy, a concept formalized by Barry Trost in 1991, evaluates the efficiency of a chemical reaction by calculating the proportion of reactant atoms incorporated into the final desired product, serving as a crucial metric for green chemistry. In redox reactions, where electron transfer processes drive chemical transformations, traditional methods frequently employ stoichiometric oxidants or reductants that become incorporated into reaction waste, fundamentally limiting their atom economy. This analysis provides a comparative examination of emerging electrochemical and biocatalytic methodologies against conventional redox synthesis approaches, focusing on quantitative atom economy metrics, waste generation profiles, and experimental protocols applicable to pharmaceutical development and industrial synthesis.

The paradigm of redox reactions is undergoing transformative redefinition driven by sustainability imperatives. Traditional approaches relying on stoichiometric oxidizing and reducing agents generate substantial molecular waste, whereas modern strategies harness electrons, light, and engineered enzymes as fundamentally more atom-efficient redox agents. This comparative guide objectively evaluates these methodologies through experimental data, focusing on atom economy, environmental impact, and practical implementation for research scientists.

Quantitative Comparison of Redox Methodologies

Table 1: Comprehensive Performance Metrics of Redox Methodologies

| Methodology | Typical Atom Economy | Key Waste Products | E-Factor | Volumetric Productivity | Redox Agent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Sacrificial Cofactor | 49-78% | Oxidized/reduced co-substrates (e.g., gluconate from glucose) | Not specified | Variable | Chemical reagents (e.g., glucose, formate) |

| Light-Driven Cyanobacterial Biocatalysis | 88% | Water, cellular biomass | 203 (including water) | 1 g L⁻¹ h⁻¹ | Photosynthetic NADPH regeneration |

| Organic Electrosynthesis | Up to 100% in cross-coupling | Hydrogen gas (valuable), minimal side products | Typically lower | Highly variable | Electrons |

| Conventional Oxidative Coupling | 30-70% | Metal salts, stoichiometric oxidants | Often high | Variable | Chemical oxidants (e.g., AgNO₃) |

Table 2: Economic and Operational Considerations

| Parameter | Traditional Chemical Redox | Electrochemical Synthesis | Photosynthetic Biocatalysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capital Investment | Standard reactor equipment | Specialized electrodes, potentiostats | Photobioreactor, lighting systems |

| Operating Costs | Replenishment of stoichiometric reagents | Electricity, electrolyte recycling | Nutrients, lighting energy |

| Waste Management | Complex purification, metal disposal | Electrolyte recycling, electrode maintenance | Biomass processing, aqueous waste |

| Reaction Scale-Up | Well-established with heat transfer considerations | Current distribution, flow cell design | Light penetration, gas exchange |

Experimental data from light-driven cyanobacterial biotransformations demonstrates substantially improved atom economy (88%) compared to conventional sacrificial cofactor systems (49-78%) [15]. This approach leverages photosynthetic NADPH regeneration from water and light, fundamentally minimizing sacrificial waste components. Similarly, electrochemical C–H amination achieves comparable yields to traditional methods while eliminating stoichiometric silver oxidants, preventing the generation of metallic waste streams [11].

The E-factor (environmental factor) quantifies total waste produced per unit of product, providing a comprehensive environmental impact assessment. The complete E-factor of 203 for cyanobacterial transformations highlights the significance of water usage in cultivation, suggesting optimization priorities for future development [15].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Light-Driven Ene-Reduction in Cyanobacteria

This procedure outlines the photosynthetic reduction of prochiral alkenes using recombinant cyanobacteria expressing ene-reductases, achieving high atom economy through biological cofactor regeneration [15].

Materials and Reagents:

- Recombinant Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 expressing ene-reductases (TsOYE C25G I67T or OYE3)

- BG-11 growth medium with appropriate antibiotics

- Substrate: 50 mM prochiral alkene (e.g., (2E)-but-2-enal)

- Flat panel photobioreactor (1 cm optical path length)

- LED illumination system (photosynthetically active radiation spectrum)

- Centrifuge for cell harvesting

- Organic solvents for product extraction (e.g., ethyl acetate)

- GC-MS or HPLC for product quantification

Experimental Procedure:

- Cyanobacteria Cultivation: Grow recombinant Synechocystis strains in BG-11 medium under continuous illumination (50 μE m⁻² s⁻¹) at 30°C with air bubbling until late exponential phase (OD₇₅₀ ≈ 6-8).

- Cell Harvesting: Concentrate cells to high density (approximately 15-20 gCDW L⁻¹) via centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 minutes.

- Biotransformation Setup: Transfer cell suspension to flat panel photobioreactor, add 50 mM substrate from concentrated stock solution, maintain temperature at 30°C with continuous illumination (150 μE m⁻² s⁻¹) and mixing.

- Reaction Monitoring: Withdraw 1 mL samples at regular intervals over 8 hours, extract with ethyl acetate, and analyze by GC-MS to determine conversion.

- Product Isolation: Terminate reaction after 8 hours (or >95% conversion), centrifuge to remove cells, extract aqueous phase with ethyl acetate (3 × 0.5 volumes), dry organic phase over anhydrous Na₂SO₄, and concentrate under reduced pressure.

- Purification: Purify crude product via flash chromatography (silica gel, hexane/ethyl acetate gradient) to yield pure reduced product.

Analytical Methods:

- Specific Activity Determination: Measure initial reaction rates (first 30 minutes) and normalize to cell dry weight (U gCDW⁻¹ where 1 U = 1 μmol product formed per minute).

- Enantiomeric Excess: Analyze chiral products using chiral GC or HPLC columns.

- Product Validation: Confirm structure via ¹H NMR, ¹³C NMR, and mass spectrometry.

Key Performance Metrics: This protocol typically achieves specific activities up to 56.1 U gCDW⁻¹, volumetric productivity of 1 g L⁻¹ h⁻¹, 87% isolated yield, and 88% atom economy [15].

Protocol 2: Electrochemical C–H Amination

This method enables oxidant-free amination of aromatic C–H bonds using electrons as traceless reagents, eliminating stoichiometric metal oxidants [11].

Materials and Reagents:

- Aromatic amide substrate (1.0 mmol)

- Secondary amine coupling partner (1.2 mmol)

- Cobalt catalyst (e.g., Co(OAc)₂, 10 mol%)

- Supporting electrolyte: NBu₄PF₆ (0.1 M)

- Solvent: tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-one (renewable solvent)

- Electrodes: Graphite anode and cathode

- Divided electrochemical cell

- Potentiostat/Galvanostat

- Nitrogen gas for degassing

Experimental Procedure:

- Electrochemical Cell Setup: Assemble divided cell with ion exchange membrane separating anode and cathode compartments.

- Anolyte Preparation: Dissolve aromatic amide substrate (1.0 mmol), cobalt catalyst (10 mol%), and supporting electrolyte (0.1 M) in tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-one (10 mL) in anode compartment.

- Catholyte Preparation: Dissolve supporting electrolyte (0.1 M) in same solvent (10 mL) in cathode compartment.

- Reaction Conditions: Degass solutions with nitrogen for 10 minutes, maintain constant current (5-10 mA/cm²) at room temperature for 2-4 hours under nitrogen atmosphere.

- Reaction Monitoring: Track conversion by TLC or LC-MS.

- Workup: After completion, combine compartments, dilute with ethyl acetate, wash with water, dry organic phase over MgSO₄, and concentrate.

- Purification: Purify crude material via flash chromatography.

Analytical Methods:

- Conversion Analysis: Quantify by ¹H NMR or GC-MS.

- Faradaic Efficiency: Calculate based on charge passed versus product formed.

- Product Characterization: Confirm via NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry.

Key Performance Metrics: This electrochemical method achieves yields comparable to traditional approaches (which use 2.5 equiv. AgNO₃) while eliminating metallic waste and generating hydrogen gas as the only byproduct [11].

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Comparative experimental workflows for photosynthetic biocatalysis (A) and electrosynthesis (B), highlighting energy inputs and byproducts.

Diagram 2: Atom economy and waste output comparison across redox methodologies, highlighting environmental impact differences.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Advanced Redox Methodologies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Ene-Reductases | Biocatalytic reduction of C=C bonds | Asymmetric synthesis of chiral intermediates | High stereoselectivity, NADPH-dependent |

| Two-Dimensional Silicon Nanosheets | Redox-mediated gold recovery from waste streams | Precious metal recycling from electronic waste | 1500 mg Au/g capacity, operates at ppb concentrations |

| Boron-Doped Diamond Electrodes | High-overpotential redox transformations | Wastewater treatment, organic electrosynthesis | Wide potential window, chemical stability |

| Vanadium Redox Flow Components | Large-scale electrochemical energy storage | Grid-scale energy storage, renewable integration | Long cycle life, decoupled power/energy |

| Ion Exchange Membranes | Separation of anolyte and catholyte | Divided electrochemical cells, flow batteries | Selective ion transport, pH stability |

| Tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-one | Renewable solvent for electrochemistry | Green alternative to traditional organic solvents | Biodegradable, good conductivity |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that electrochemical and photosynthetic biocatalytic methods offer substantial improvements in atom economy and waste reduction compared to traditional redox processes. The experimental data confirms that these approaches can achieve dramatically lower environmental impact while maintaining synthetic efficiency, with light-driven cyanobacterial systems reaching 88% atom economy and electrochemical methods potentially approaching 100% atom efficiency in optimized cases.

Future research directions should address remaining challenges, including the scalability of photobioreactors, electrode fouling in electrosynthesis, and the development of continuous-flow systems for both methodologies. The integration of artificial intelligence for reaction optimization and the discovery of novel redox-active biomolecules and electrode materials represent promising frontiers. As these technologies mature, their adoption in pharmaceutical development and industrial synthesis will be crucial for advancing sustainable chemical manufacturing.

The Role of Renewable Solvents and Materials in Modern Synthesis

The transition from traditional solvents to green alternatives represents a pivotal shift toward sustainable science, reducing toxicity and environmental impact while maintaining analytical efficacy [16]. This movement is particularly evident in modern synthetic chemistry, where renewable solvents—derived from plant-based materials rather than petroleum-based sources—are gaining significant traction across research and industrial applications [16] [17]. The adoption of these solvents aligns with the principles of green chemistry, focusing on reducing or eliminating hazardous substances throughout chemical processes [18]. In parallel, electrochemical synthesis has emerged as a powerful green alternative to traditional methods, offering unique opportunities to conduct redox reactions under milder conditions without stoichiometric oxidants or reductants [11] [14]. This comparative analysis examines the performance, applications, and practical implementation of renewable solvents and materials, with a specific focus on their role in advancing sustainable electrochemical synthesis for researchers and drug development professionals.

Green Solvents: Types, Properties, and Comparative Performance

Classification and Characteristics of Renewable Solvents

Renewable solvents are primarily categorized based on their origin and chemical structure. Bio-based solvents obtained from natural and renewable resources represent some of the most promising alternatives to conventional petrochemical solvents [16]. These can be further classified into cereal/sugar-based solvents (e.g., bio-ethanol from sugarcane and corn), oleo-proteinaceous-based solvents (e.g., fatty acid esters from oilseed plants), and wood-based solvents (e.g., terpenes like D-limonene from orange peels) [16]. Another significant category includes ionic liquids (ILs), which are composed entirely of ions with melting points below 100°C, offering negligible vapor pressure and high thermal stability [16]. Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) represent a related class, formed by combining a hydrogen bond donor and acceptor, sharing similar advantages with ILs but with simpler synthesis and cheaper components [16]. Supercritical fluids, particularly supercritical carbon dioxide (scCO₂), offer additional green alternatives with tunable solvent properties based on pressure and temperature conditions [16] [19].

The ideal green solvent exhibits specific characteristics that align with sustainability goals. Biodegradability and low toxicity are essential properties ensuring minimal environmental harm upon disposal [16]. Furthermore, low volatility reduces VOC emissions, contributing to better air quality and reduced health risks, while reduced flammability enhances safety during handling and storage [16]. Perhaps most critically, these solvents must maintain compatibility with analytical techniques and diverse synthetic procedures without compromising performance [16]. For industrial applicability, green solvents should demonstrate recyclability and be produced through energy-efficient methods using renewable feedstocks, as the sustainability assessment must consider the entire lifecycle from synthesis to disposal [16].

Performance Comparison: Renewable vs. Conventional Solvents

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Solvent Properties and Environmental Impact

| Solvent Type | Renewable Source | Boiling Point (°C) | Toxicity (LD50 mg/kg) | Environmental Impact | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terpenes (e.g., d-limonene) | Citrus peels, wood | 175-190 | >2,500 (similar to table salt) [17] | Low carbon footprint (0.4 kg CO₂ eq/kg) [17] | Organic electronics, cleaning, degreasing [17] |

| Bio-ethanol | Sugarcane, corn, wheat | 78 | Variable by grade | Renewable feedstock | Extraction, reaction medium [16] |

| Ethyl lactate | Lactic acid (fermentation) | 154 | Low toxicity | Biodegradable | Cleaning, coatings, pharmaceuticals [19] |

| Supercritical CO₂ | Industrial byproduct | 31 (at critical point) | Non-toxic | Non-flammable, recyclable | Decaffeination, extraction [19] |

| Chloroform (conventional) | Petroleum-based | 61 | ~900 [17] | High carbon footprint (3.4 kg CO₂ eq/kg) [17] | Organic synthesis, previously electronics |

| DMF (conventional) | Petroleum-based | 153 | ~2,800 | "Substance of very high concern" (EU REACH) [20] | Dipolar aprotic solvent |

Table 2: Electrochemical Performance in Different Solvent Systems

| Solvent System | Conductivity | Functional Group Tolerance | Reaction Efficiency | Scalability Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water/Organic Mixtures | Moderate to high with electrolytes | Variable; improved with cosolvents | Good for many transformations | High with proper waste treatment [20] |

| Pure Water | High with electrolytes | Limited by substrate solubility | Limited to water-soluble compounds | Requires extraction steps [20] |

| Pure Organic Solvents | Lower; requires higher electrolyte concentration | Generally excellent | High for diverse reactions | Solvent recovery challenges [20] |

| Renewable Solvents (e.g., Cyrene) | Moderate | Comparable to traditional dipolar aprotic | Promising for various electrosyntheses | Developing; requires optimization [20] |

The data reveals that renewable solvents offer substantially improved safety profiles and reduced environmental impact compared to conventional solvents, while maintaining competitive performance in various applications. Terpene solvents, for instance, demonstrate particular promise for organic electronics fabrication, achieving device performances comparable to those processed with toxic halogenated solvents like chloroform [17]. In electrochemical applications, solvent systems significantly influence conductivity and compatibility, with water-organic mixtures offering a balanced approach for many electrosynthetic processes [20].

Electrochemical vs. Traditional Synthesis: A Comparative Framework

Fundamental Principles and Advantages

Electrochemical synthesis represents a transformative approach to chemical transformations, utilizing electrons as clean reagents to drive oxidation and reduction processes. This methodology aligns with nine of the twelve principles of green chemistry, offering significant environmental benefits over traditional approaches [10]. A key advantage includes inherent sustainability, as electrochemical reactions can proceed under exogenous-oxidant-free and reductant-free conditions, eliminating the need for stoichiometric amounts of chemical oxidants or reductants that inevitably generate hazardous waste [11]. This characteristic makes electrochemistry particularly valuable for pharmaceutical applications where purification from excess reagents can be challenging.

The environmental benefits of electrochemical synthesis extend beyond reagent elimination. These methods typically operate under milder conditions (room temperature and ambient pressure) compared to many traditional thermal reactions, resulting in lower energy consumption [11]. Electrochemical processes also demonstrate superior atom economy in many cases, particularly for oxidative cross-coupling reactions where the only byproduct is hydrogen gas rather than the waste associated with chemical oxidants [11]. Additionally, the reaction control afforded by electrochemical methods—through adjustment of current or potential—enables selective transformations that might be difficult to achieve with conventional reagents, along with enhanced functional group tolerance [11]. The scalability potential of electrochemical synthesis has been demonstrated in industrial processes such as the Monsanto adiponitrile process, highlighting its practical applicability [14].

Limitations and Practical Challenges

Despite its significant advantages, electrochemical synthesis faces several practical challenges that must be addressed for wider adoption. The specialized equipment requirement represents a substantial barrier, as electrochemical cells (often needing three-electrode systems) and potentiostats entail higher initial investment compared to traditional glassware [11] [10]. Solvent and electrolyte limitations also present challenges, as most electrochemical reactions require supporting electrolytes to provide sufficient conductivity, and solvent choice is constrained by conductivity requirements—with poorly conductive solvents like tetrahydrofuran and toluene presenting difficulties [11]. Furthermore, the use of metal catalysts in undivided cells is relatively limited because metal cations may be reduced at the cathode to zero-valent metals, and expensive ion exchange membranes are often necessary for divided cell setups [11]. Finally, the perception of electrochemistry as a "black box" with complex optimization parameters (electrode materials, cell design, potential/current control) discourages some synthetic chemists from adopting these methods [14].

Table 3: Direct Comparison: Electrochemical vs. Traditional Synthesis Methods

| Parameter | Electrochemical Synthesis | Traditional Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Oxidants/Reductants | Electron transfer at electrodes; no stoichiometric reagents needed [11] | Stoichiometric oxidants/reductants required (e.g., AgNO₃, MnO₂) [11] |

| Reaction Byproducts | Often H₂ gas in cross-couplings (valuable) [11] | Metal salts, oxidized/reduced reagent derivatives [11] |

| Reaction Conditions | Typically mild (room temperature, ambient pressure) [11] | Often elevated temperatures/pressures required |

| Functional Group Tolerance | Generally excellent due to tunable potential [11] | Variable; depends on reagent selectivity |

| Reaction Control | Precise via potential/current adjustment [11] | Limited to temperature, concentration, catalyst |

| Scalability | Demonstrated in industrial processes (e.g., adiponitrile) [14] | Well-established for many transformations |

| Equipment Cost | Higher initial investment (cell, potentiostat) [10] | Standard glassware typically sufficient |

| Operator Expertise | Requires electrochemical knowledge [14] | Familiar to most synthetic chemists |

| Solvent Constraints | Must support electrolyte conductivity [20] | Broader solvent selection possible |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Representative Electrochemical Synthesis Protocol

The following detailed methodology illustrates a specific electrochemical C–H amination reaction, demonstrating the integration of renewable solvents in modern electrosynthesis:

Reaction Setup: Conduct the electrochemical transformation in an undivided cell equipped with a platinum plate cathode and a carbon rod anode [10]. The reaction employs tetrabutylammonium acetate as both electrolyte and hydrogen-bond acceptor, facilitating the breaking of nitrogen-hydrogen bonds [10].

Reaction Conditions: Prepare a solution of the sulfonamide substrate (5, 0.2 mmol) and tetrabutylammonium acetate (0.4 mmol) in the chosen renewable solvent (e.g., tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-one, 10 mL) [11] [10]. Apply a constant current of 8 mA and stir the reaction mixture at room temperature for 4-6 hours under nitrogen atmosphere [10].

Reaction Mechanism: The process begins with complex formation between sulfonamide and acetate. Anodic oxidation generates an N-centered radical intermediate, which undergoes 1,5-hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) to form a carbon-centered radical. Further oxidation yields a carbocation intermediate, which undergoes nucleophilic attack and proton elimination to form the cyclized pyrrolidine product [10]. Concurrent reduction of protons at the cathode produces hydrogen gas as the only byproduct [10].

Workup and Isolation: After complete conversion (monitored by TLC or LCMS), evaporate the solvent under reduced pressure. Purify the crude product by flash chromatography on silica gel to obtain the pure pyrrolidine derivatives in good to excellent yields (typically 70-85%) [10].

Terpene Solvent Formulation for Organic Electronics

Ink Preparation: For organic electronic applications such as OPV fabrication, prepare terpene-based binary solvent formulations using HSP (Hansen Solubility Parameters) guidance. Specifically, for PM6:BTP-eC9 systems, formulate eucalyptol:tetralin (Eu:Tet), limonene:indan (Lim:Ind), pinene:ethyl phenyl sulfide (Pin:EPS), or menthone:tetralin (Men:Tet) mixtures at optimal volumetric ratios determined through solubility studies [17].

Film Formation: Dissolve the organic semiconductor materials in the terpene-based formulations at concentrations of 5-10 mg/mL. Spin-coat or blade-coat the resulting inks onto pre-cleaned substrates, controlling the drying kinetics through precise temperature regulation (typically 80-100°C for initial drying, followed by 110-130°C for annealing) [17].

Device Fabrication: Complete the device structure by evaporating electrode materials under high vacuum. Encapsulate the finished devices for performance testing and stability assessments [17].

Performance Validation: Characterize the resulting organic electronic devices (OPVs, OLEDs, OFETs) using current-density-voltage measurements, external quantum efficiency analysis, and charge transport studies. Compare performance metrics with devices fabricated using conventional toxic solvents like chloroform [17].

Visualization of Key Concepts and Workflows

Diagram 1: Renewable solvent selection framework based on Hansen Solubility Parameters (HSP), toxicity, and renewability criteria [17].

Diagram 2: Comparative pathways highlighting the waste-reduction advantage of electrochemical synthesis over traditional methods [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Renewable Solvent Electrochemical Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Renewable Alternatives | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolytes | Provide conductivity in solvent systems | Tetrabutylammonium acetate [10] | Also acts as hydrogen-bond acceptor in C–H amination |

| Electrode Materials | Electron transfer surfaces; influence reaction selectivity | Carbon-based electrodes (rods, felt) [10] | Preferable to precious metals for sustainability |

| Terpene Solvents | Renewable processing medium for diverse applications | d-Limonene, eucalyptol, pinene [16] [17] | Use HSP framework for formulation optimization [17] |

| Bio-based Co-solvents | Modify solubility and drying properties | Tetralin, indan (from biomass) [17] | Enable processing of high-performance organic semiconductors |

| Ionic Liquids | Tunable solvents with negligible vapor pressure | Bio-derived cations/anions [16] | Ensure comprehensive lifecycle assessment for green claims [16] |

| Metal Catalysts | Mediate electron transfer; improve selectivity | Earth-abundant metals (Fe, Co, Ni) [10] | Preferable to precious metals; consider electrochemical recycling |

The integration of renewable solvents with electrochemical synthesis represents a powerful combination for advancing sustainable chemical production. The comparative data presented demonstrates that bio-based solvents can match or even exceed the performance of conventional solvents while offering substantially improved environmental and safety profiles [17]. Similarly, electrochemical methods provide distinct advantages over traditional synthesis in terms of waste reduction, energy efficiency, and reaction control [11]. Future developments in this field will likely focus on addressing current limitations, including the development of more economical electrochemical equipment, minimization or elimination of supporting electrolytes, and creation of specialized continuous-flow electrochemical reactors for improved scalability [11] [14]. Additionally, the expansion of asymmetric electrochemical synthesis and further exploration of paired electrolysis approaches that simultaneously utilize both anodic and cathodic reactions will enhance the overall atom economy of these processes [11]. As the field progresses, the ongoing collaboration between material scientists, electrochemists, and process engineers will be essential for optimizing these sustainable synthesis platforms and accelerating their adoption across pharmaceutical development and industrial chemical production.

Innovative Electro-organic Methods and Their Drug Discovery Applications

Oxidant- and Reductant-Free C–H Functionalization for Streamlined Synthesis

The landscape of organic synthesis, particularly in pharmaceutical development, is undergoing a significant transformation driven by the pursuit of sustainability and efficiency. Traditional synthetic methodologies for constructing carbon-carbon and carbon-heteroatom bonds often rely on pre-functionalized substrates and stoichiometric quantities of oxidants or reductants, generating substantial waste and increasing process complexity. Against this backdrop, oxidant- and reductant-free C–H functionalization has emerged as a powerful paradigm offering improved atom economy and step-economy. This review provides a comparative analysis of two dominant approaches enabling this transformation: electrochemical methods and advanced transition metal catalysis. We objectively evaluate these strategies through quantitative performance metrics, detailed experimental protocols, and sustainability assessments to guide researchers in selecting optimal methodologies for streamlined synthesis.

Two primary technological platforms have enabled oxidant- and reductant-free C–H functionalization: electrochemical synthesis that utilizes electrons as traceless redox agents, and advanced transition metal catalysis that employs designed catalyst systems operating without external oxidants.

Electrochemical C–H Functionalization

Electrochemical methods leverage electrical energy to drive synthetic transformations through direct electron transfer at electrode surfaces, eliminating requirement for stoichiometric chemical oxidants or reductants. This approach uses electrons and electron holes as traceless redox equivalents, significantly enhancing atom economy while diminishing dependence on fossil-derived energy resources [21]. The methodology enables precise modulation of redox conditions through optimized electrical parameters (current, voltage, current density) and electrochemical conditions (electrode materials, electrolyte, temperature) [21].

Recent advances have demonstrated the versatility of electrochemical C–H functionalization for diverse bond-forming reactions. Frontiera and colleagues have developed metal catalyst- and oxidant-free electrochemical C–H functionalization of nitrogen-containing heterocycles for constructing C–C and C–X bonds [22]. Similarly, Lei and coworkers have established exogenous-oxidant-free electrochemical oxidative C–H phosphonylation protocols that accommodate both C(sp²)–H and C(sp³)–H substrates without metal catalysts [23].

Transition Metal-Catalyzed C–H Functionalization Without External Oxidants

Traditional transition metal-catalyzed C–H functionalization typically requires stoichiometric oxidants to turn over catalytic cycles by re-oxidizing the metal catalyst. Recent innovations in catalyst design have enabled oxidant-free systems through several mechanistic approaches:

Catalyst Systems with Inherent Oxidant-Free Cycles: Awuah and colleagues developed stable tricoordinate Au(I) catalysts that facilitate direct C–H arylation of simple arenes with aryl iodides under aerobic conditions without external oxidants [24]. These systems leverage the unique redox properties of gold catalysis, where the challenge of oxidant-free catalysis is particularly acute due to high redox potentials that make Au(I) sluggish in undergoing oxidative addition [24].

Ruthenium-Catalyzed Remote C–H Functionalization: Modern ruthenium catalysis has enabled remarkable position-selectivity in C–H functionalization. As demonstrated in recent pharmaceutical applications, ruthenium catalysts can leverage inherent Lewis-basic motifs in complex drug molecules to direct meta-C–H alkylation with complete position-selectivity without requiring external oxidants [25].

Table 1: Comparison of Oxidant-Free C–H Functionalization Methodologies

| Methodology | Key Features | Typical Yield Range | Catalyst System | Position Selectivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical C–H Functionalization | Traceless electrons, mild conditions, divided/undivided cells | 33-92% [23] [21] | Metal-free or catalytic metal usage | Controlled by substrate electronics and electrode potential |

| Gold Catalysis | Aerobic conditions, shelf-stable catalysts, functional group tolerance | Up to >80% [24] | Tricoordinate Au(I) complexes with phenanthroline ligands | Directed by coupling partner electronics |

| Ruthenium Catalysis | Remote meta-selectivity, broad directing group compatibility | Moderate to excellent yields [25] | [Ru(O₂CMes)₂(p-cymene)] with phosphine ligands | Proximity-induced with Lewis-basic sites |

Experimental Protocols and Performance Data

Electrochemical C–H Phosphonylation Protocol

Representative Procedure for Electrochemical C–H Phosphonylation (adapted from Yuan et al. [23]):

- Reaction Setup: Conduct reactions in an undivided electrochemical cell equipped with a carbon rod anode (6 × 70 mm) and platinum plate cathode (10 × 10 mm).

- Reaction Conditions: Charge the cell with 2-phenylimidazo[1,2-a]pyridine (0.3 mmol), triethyl phosphite (0.6 mmol), and nBu₄NPF₆ (0.1 mmol) in anhydrous MeCN (10 mL).

- Electrolysis: Perform electrolysis at constant current (4 mA) for 6 hours (3 F mol⁻¹) at 50°C with magnetic stirring.

- Workup: After completion, concentrate the reaction mixture under reduced pressure and purify by flash column chromatography (silica gel, ethyl acetate/petroleum ether) to obtain the phosphonylation product.

- Scale-Up: For gram-scale synthesis (6.0 mmol), maintain similar conditions with proportional scaling of reagents and solvent, achieving 55% yield for C(sp²)–H phosphonylation and 50% yield for C(sp³)–H phosphonylation [23].

Performance Analysis: This protocol demonstrates exceptional breadth, successfully accommodating diverse heteroarenes including 2-phenylimidazo[1,2-a]pyridines with electron-donating groups (yields: moderate to good), electron-withdrawing groups (moderate yield), and various methyl-substituted derivatives (moderate to good yields). The methodology extends to challenging C(sp³)–H substrates including xanthene (87% yield) and N-methyl-9,10-dihydroacridine (74% yield) [23].

Ruthenium-Catalyzed Meta-C–H Alkylation Protocol

Representative Procedure for Meta-C–H Alkylation (adapted from [25]):

- Catalyst Preparation: Employ [Ru(O₂CMes)₂(p-cymene)] as catalyst in combination with P(4-CF₃C₆H₄)₃ ligand.

- Reaction Setup: In a glovebox, combine substrate (1.0 equiv), alkyl bromide (2.0 equiv), K₂CO₃ (2.0 equiv), catalyst (10 mol%), and ligand (20 mol%) in 2-MeTHF (0.1 M concentration).

- Reaction Conditions: Heat the mixture at 80°C for 16-24 hours with stirring.

- Workup: After cooling, dilute with ethyl acetate, wash with brine, dry over Na₂SO₄, concentrate, and purify by flash chromatography.

- HTE Approach: High-throughput experimentation employing automation technologies enables rapid optimization with minimized resource consumption [25].

Performance Analysis: This transformation exhibits remarkable directing group scope, successfully leveraging heterocycles ubiquitous in pharmaceuticals including pyrimidines, pyrazoles, oxazolines, triazines, and thiazoles. The system maintains efficiency across diverse alkyl bromides with different electronic properties (nucleophilic and electrophilic), though slightly reduced efficacy was observed for phosphonate and cyclopropyl derivatives [25].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics for Oxidant-Free C–H Functionalization

| Reaction Type | Specific Transformation | Representative Yield | Catalyst Loading | Reaction Conditions | Functional Group Tolerance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|