Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Advanced Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS), a powerful, non-destructive analytical technique essential for researchers and drug development professionals.

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Advanced Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS), a powerful, non-destructive analytical technique essential for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, including the theoretical background of measuring a system's impedance to a small AC signal, data representation via Nyquist and Bode plots, and equivalent circuit modeling. The scope extends to advanced methodological applications in biosensing, such as the label-free detection of pathogens and the analysis of bio-recognition events at electrode interfaces, highlighting the impact of nanomaterials on enhancing sensor performance. Practical guidance on troubleshooting data quality, optimizing measurements, and validating results is included, alongside a comparative analysis with other electrochemical techniques. The article synthesizes how EIS serves as a critical tool for advancing biomedical research, from diagnostics to drug development, by enabling sensitive, real-time, and label-free analysis of complex biological systems.

Understanding EIS: Core Principles and System Fundamentals

What is EIS? Defining Impedance in Electrochemical Systems

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) is a powerful analytical technique used to characterize materials and interfaces by measuring their response to an applied alternating current (AC) signal. Fundamentally, impedance is a generalized form of resistance that extends to AC circuits, capturing not only the dissipation of energy but also its storage and release over time [1]. In electrochemical systems, EIS probes the interaction of a sample with a time-varying electric field, yielding information about how the sample stores and dissipates energy, thereby enabling the parameterization of underlying physical and chemical processes [2]. This technique has become a cornerstone for the in-situ characterization of electrochemical, electrical, and interfacial phenomena in fields ranging from energy storage to sensor development [2].

Core Principles of EIS

From Resistance to Complex Impedance

The concept of impedance (Z) is analogous to Ohm's Law but for alternating current systems. Where Ohm's Law defines resistance (R) as the ratio of voltage (E) to current (I) for direct current (DC), impedance is defined as the ratio of the time-varying voltage to the time-varying current [1] [3]:

Z(ω) = E(ω) / I(ω)

In a typical potentiostatic EIS experiment, a small sinusoidal potential (excitation signal) is applied to an electrochemical cell:

E(t) = E₀ sin(ωt)

where E₀ is the amplitude and ω is the radial frequency [1]. In a linear system, the current response is a sinusoid at the same frequency but shifted in phase (Φ):

I(t) = I₀ sin(ωt + Φ)

This phase shift and amplitude change are captured by the complex impedance, which can be expressed using Euler's relationship as [1]:

Z(ω) = Z₀e^(jΦ) = Z₀(cos Φ + j sin Φ)

This formulation separates the impedance into a real part (Z_real = Z₀ cos Φ), representing energy dissipation, and an imaginary part (Z_imag = Z₀ sin Φ), representing energy storage [3].

Table 1: Key Differences Between Resistance and Impedance

| Property | Resistance (R) | Impedance (Z) |

|---|---|---|

| Signal Type | Direct Current (DC) | Alternating Current (AC) |

| Frequency Dependence | Independent of frequency | Dependent on frequency |

| Phase Relationship | Current & voltage are in phase | Current & voltage can be out of phase |

| Mathematical Representation | Real number | Complex number (Real + Imaginary parts) |

Essential Conditions for EIS Measurements

Reliable EIS measurements require two critical conditions [1]:

- Linearity: The electrochemical system must behave in a pseudo-linear manner. This is achieved by applying a very small amplitude excitation signal (typically 1-10 mV), ensuring the response is confined to a nearly linear segment of the current-voltage curve.

- Stability: The system must be at a steady state throughout the measurement, which can take from minutes to hours. Drift in the system due to factors like adsorption, temperature changes, or degradation can lead to inaccurate results.

Data Presentation and Equivalent Circuit Elements

Nyquist and Bode Plots

EIS data is most commonly presented in two types of plots:

- Nyquist Plot: This graph plots the negative imaginary impedance (

-Z'') on the Y-axis against the real impedance (Z') on the X-axis. Each point on the plot represents the impedance at one frequency, though the frequency is not explicitly shown. High-frequency data typically appear on the left side of the plot, with frequency decreasing towards the right. A Nyquist plot for a simple circuit with one "time constant" often results in a semicircle [1] [3]. - Bode Plot: This display uses two separate graphs with logarithmic frequency on the X-axis: the magnitude of the impedance (

|Z|) on a logarithmic Y-axis, and the phase shift (Φ) on a linear Y-axis. Unlike the Nyquist plot, the Bode plot explicitly shows frequency information [1].

Common Equivalent Circuit Elements

EIS data are commonly analyzed by fitting to an equivalent electrical circuit model, where each element represents a specific physical process in the electrochemical system [1]. The impedance of common circuit elements is summarized below.

Table 2: Impedance of Common Electrical Circuit Elements

| Component | Current vs. Voltage Relationship | Impedance (Z) |

|---|---|---|

| Resistor (R) | E = I R |

Z = R |

| Capacitor (C) | I = C dE/dt |

Z = 1 / (jωC) |

| Inductor (L) | E = L di/dt |

Z = jωL |

These fundamental elements can be combined in series and parallel to model more complex electrochemical interfaces, such as a double-layer capacitor in parallel with a charge-transfer resistor.

Experimental Protocol: Basic EIS Measurement

Materials and Equipment

- Potentiostat/Galvanostat: An instrument capable of applying a small sinusoidal potential or current signal and measuring the resulting response. Modern systems often include a Frequency Response Analyzer (FRA) [3].

- Electrochemical Cell: A three-electrode configuration is standard.

- Working Electrode (WE): The electrode of interest, where the reaction occurs.

- Counter Electrode (CE): Completes the electrical circuit.

- Reference Electrode (RE): Provides a stable, known potential against which the WE is measured [3].

- Electrolyte: A solution containing ions to facilitate current flow.

- Software: For instrument control, data acquisition, and analysis (e.g., ZView for circuit modelling) [2].

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Cell Setup: Assemble the electrochemical cell with the working, reference, and counter electrodes immersed in the electrolyte. Ensure all connections are secure.

- Stabilization: Allow the system to reach a stable open-circuit potential (OCP) to ensure a steady state before measurement [1].

- Parameter Configuration:

- Set the DC potential or current bias around which the AC signal will oscillate.

- Define the frequency range. A typical spectrum is collected from a high frequency (~1 MHz or 100 kHz) down to a low frequency (~10 mHz or 1 Hz), with multiple points per decade measured on a logarithmic scale [3] [4].

- Set the amplitude of the AC perturbation. For potentiostatic EIS, this is typically a 1-10 mV sinusoidal potential signal to ensure pseudo-linearity [1] [3].

- Data Acquisition: Initiate the measurement. The potentiostat applies each sinusoidal potential frequency, measures the current response, and uses a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to convert the time-domain signals into frequency-domain data, extracting the potential amplitude (

E₀), current amplitude (I₀), and phase shift (Φ) at each frequency [1] [3]. - Data Validation: Apply checks such as the Kramers-Kronig relations to evaluate the quality, linearity, and stability of the measured impedance data [2].

- Data Analysis: Model the data using an equivalent circuit to extract physical parameters. For example, in a conductivity measurement, the bulk resistance (

R_b) can be obtained from the high-frequency intercept of a Nyquist plot with the real axis, allowing conductivity (σ) to be calculated asσ = t / (R_b * A), wheretis the sample thickness andAis the electrode area [4].

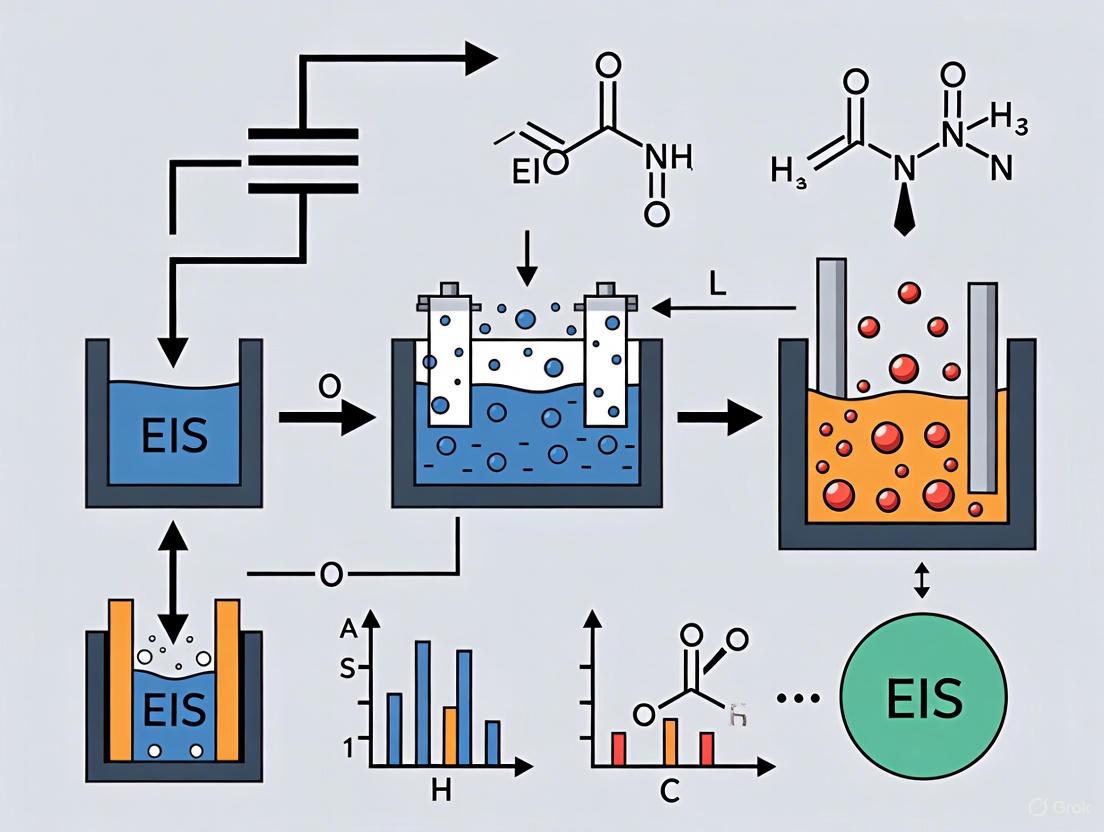

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of an EIS experiment:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for EIS

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Potentiostat with FRA | Core instrument for applying precise potential/current signals and measuring the high-precision frequency response [3]. |

| Standard Electrolytes (e.g., KCl, K3Fe(CN)6) | Provide conductive medium; redox-active species allow study of charge-transfer kinetics. |

| Reference Electrodes (e.g., Ag/AgCl, SCE) | Provide a stable, known reference potential for the working electrode [3]. |

| Electrode Polishing Kits (Alumina, Diamond Paste) | Ensure reproducible, clean, and smooth working electrode surfaces. |

| Software for Circuit Fitting (e.g., ZView, EC-Lab) | Enables modeling of impedance data with equivalent circuits to extract physical parameters [2]. |

| Faraday Cage | Shields the electrochemical cell from external electromagnetic interference for low-noise measurements. |

Advanced Applications and Emerging Techniques

EIS finds widespread application in the characterization of energy storage and conversion devices like batteries, fuel cells, and solar cells [2] [5] [6]. In battery research, EIS is used to quantify charge-transfer resistance, double-layer capacitance, and diffusion coefficients, which are critical for determining State of Charge (SOC) and State of Health (SOH) [6].

Emerging techniques are pushing the boundaries of traditional EIS. Mechano-electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (MEIS) is a novel technique that complements EIS by probing coupled mechanical-electrochemical dynamics. MEIS applies a sinusoidal current and measures the resulting pressure fluctuations, linking mechanical properties like stiffness to electrochemical states [5]. The field is also moving towards digitalization, with open-source platforms being developed to automate EIS data analysis and apply machine learning for improved diagnostics, such as precise battery temperature estimation using Support Vector Regression (SVR) [7]. Future developments are expected to further integrate machine learning and analyze higher harmonics for more sensitive analysis of in-situ phenomena [2].

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) is a powerful analytical technique used to investigate the properties of electrochemical systems. By applying a small amplitude sinusoidal potential (or current) across a range of frequencies and measuring the system's response, EIS provides a non-destructive method to probe complex electrochemical processes [1] [3]. The analysis of this response rests on a robust mathematical framework of key equations and transfer functions, which allow researchers to model the system as an equivalent electrical circuit. This application note details the core mathematical principles, data presentation formats, and experimental protocols essential for employing EIS in research, particularly for scientists and drug development professionals.

Fundamental Principles and Key Equations

The fundamental principle of EIS is the extension of Ohm's Law to systems subjected to an alternating current (AC) signal. While Ohm's Law ((E = I \times R)) describes the relationship between a direct current (DC) voltage ((E)) and current ((I)) via a resistance ((R)), impedance ((Z)) is the analogous property for AC circuits, encompassing both resistance and reactance [3].

In a potentiostatic EIS experiment, a sinusoidal potential of the form shown in Equation 1 is applied to the electrochemical cell. Equation 1: Applied Potential [ Et = E0 \times \sin(\omega t) ] Where (Et) is the potential at time (t), (E0) is the amplitude of the signal, and (\omega) is the radial frequency (in radians/second), related to frequency (f) (in Hertz) by (\omega = 2\pi f) [1].

The current response from a linear, time-invariant system will be a sinusoid at the same frequency but shifted in phase, as described in Equation 2. Equation 2: Current Response [ It = I0 \times \sin(\omega t + \phi) ] Where (I_0) is the current amplitude and (\phi) is the phase shift [1].

The impedance is then defined as the ratio of the voltage to the current in the frequency domain. Using Euler's relationship, this can be elegantly expressed as a complex function (Equation 3), which is the fundamental transfer function for EIS [1]. Equation 3: Complex Impedance [ Z(\omega) = \frac{E(\omega)}{I(\omega)} = Z0 \times e^{j\phi} = Z0 (\cos\phi + j\sin\phi) ] This complex impedance can be separated into a real part, (Z{re}), and an imaginary part, (Z{im}) (Equation 4). Equation 4: Real and Imaginary Impedance [ Z(\omega) = Z{re} + jZ{im} ] Where:

- (Z{re} = Z0 \cos\phi)

- (Z{im} = Z0 \sin\phi) [3]

The magnitude of the impedance is given by (|Z| = \sqrt{Z{re}^2 + Z{im}^2}) and the phase angle by (\phi = \arctan(Z{im} / Z{re})) [1].

Circuit Elements and Their Impedance

The building blocks for equivalent circuit models are standard electrical components. Their impedance behaviors are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Impedance of Common Electrical Circuit Elements

| Component | Current vs. Voltage Relationship | Impedance ((Z)) |

|---|---|---|

| Resistor | (E = I R) | (R) |

| Capacitor | (I = C \frac{dE}{dt}) | (\frac{1}{j\omega C}) |

| Inductor | (E = L \frac{di}{dt}) | (j\omega L) |

As shown, the impedance of a resistor is real and independent of frequency. A capacitor's impedance is purely imaginary and decreases with frequency, while an inductor's impedance is also purely imaginary but increases with frequency [1]. The current through a resistor is in phase with the voltage, whereas for a capacitor, the current leads the voltage by 90 degrees.

Data Presentation and Visualization

Nyquist and Bode Plots

Impedance data is most commonly presented in two types of plots, each offering different insights.

Nyquist Plot: This plot displays the negative of the imaginary impedance ((-Z{im})) on the vertical axis against the real impedance ((Z{re})) on the horizontal axis. Each point on the plot represents the impedance at one frequency, though the frequency is not explicitly shown. The plot typically results in one or more semicircles or arcs. The high-frequency data appears on the left side of the plot, and the low-frequency data on the right [1] [3]. The impedance vector at a given frequency can be represented as an arrow from the origin to a data point, with a length (|Z|) and an angle (\phi) to the real axis.

Bode Plot: This presentation uses two separate graphs. The first plots the logarithm of the impedance magnitude ((\log |Z|)) against the logarithm of frequency ((\log f)). The second plots the phase shift ((\phi)) in degrees against (\log f). Unlike the Nyquist plot, the Bode plot explicitly shows the frequency dependence of both the impedance magnitude and the phase angle [1].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow from the initial EIS experiment to data transformation and final presentation.

Equivalent Circuit Modeling

To extract physical meaning from EIS data, the total impedance of the system is modeled using an equivalent circuit composed of the basic elements in Table 1. A common model for a simple electrode-electrolyte interface is the Randles circuit, which includes the solution resistance ((Rs)), the charge transfer resistance ((R{ct})), and the double-layer capacitance ((C_{dl})), often with a constant phase element (CPE) to account for non-ideal capacitive behavior.

The total impedance of a circuit is the sum of the impedances of elements in series. For elements in parallel, the total admittance (the inverse of impedance, (Y = 1/Z)) is the sum of the individual admittances. The impedance for the Randles circuit is given by: Equation 5: Randles Circuit Impedance [ Z(\omega) = Rs + \frac{1}{j\omega C{dl} + \frac{1}{R_{ct}}} ]

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Basic Potentiostatic EIS Measurement

1. Objective: To acquire the electrochemical impedance spectrum of a sample in a three-electrode configuration. 2. Materials: See Section 5, "The Scientist's Toolkit". 3. Procedure: - Cell Setup: Place the working, counter, and reference electrodes into the electrochemical cell containing the electrolyte and analyte. Ensure stable positioning and connection to the potentiostat. - DC Potential Selection: Determine a stable DC potential (setpoint, (E{dc})) around which the small AC signal will be applied. This is often the open circuit potential (OCP) or a potential of interest for a Faradaic process. - AC Parameters: Set the AC potential amplitude ((E0)) to a value that ensures the system response is pseudo-linear, typically 1-10 mV [1]. Define the frequency range, usually from a high frequency (e.g., 100 kHz or 1 MHz) down to a low frequency (e.g., 10 mHz or 0.1 Hz). Use 5-10 measurement points per decade of frequency on a logarithmic scale. - Data Acquisition: Initiate the EIS sequence. The instrument will apply the DC potential with the superimposed AC sine wave at each frequency, measure the current response, and use a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to calculate the impedance components ((Z{re}), (Z{im}), (|Z|), (\phi)) [3]. - Data Validation: Ensure the system is at a steady state throughout the measurement, which can take from minutes to hours. Drift can lead to inaccurate results. Check data consistency using the Kramers-Kronig relations if supported by the instrument software [1] [8].

Protocol for Rapid EIS for Sorting/Screening

For high-throughput applications, such as screening battery materials or biological samples, a rapid EIS method can be employed [8]. 1. Objective: To acquire sufficient EIS data for sample differentiation in a significantly reduced time. 2. Key Modifications: - Excitation Signal: Use a multisine excitation signal containing multiple frequencies simultaneously instead of a single-frequency sine wave. - Partial Frequency Band: Focus on a specific, diagnostically relevant frequency band (e.g., 1 Hz to 10,000 Hz) to reduce acquisition time. Data acquisition can be reduced to as little as 5 seconds [8]. - Feature Selection: For sorting applications where absolute parameter values are less critical than consistency, use the imaginary part of the impedance ((Z_{im})) from selected frequency bands for analysis, as it is less susceptible to drift caused by fixture connections [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for EIS

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Potentiostat/Galvanostat with FRA | The core instrument that applies the potential/current and measures the response. The Frequency Response Analyzer (FRA) is essential for impedance measurements [3]. |

| Electrochemical Cell | A container that holds the electrolyte solution and provides a controlled environment for the experiment. |

| Three-Electrode Setup | Working Electrode (WE): The electrode where the reaction of interest occurs (e.g., glassy carbon, gold disk). Counter Electrode (CE): A conductor (e.g., platinum wire) that completes the circuit. Reference Electrode (RE): Provides a stable, known potential (e.g., Ag/AgCl, SCE) against which the WE potential is measured [3]. |

| Electrolyte | A solution containing ions to support electrical conductivity. The choice of electrolyte (e.g., PBS for biological systems, lithium salts for battery research) is critical. |

| Redox Probe (for Faradaic EIS) | A reversible redox couple (e.g., ([Fe(CN)_6]^{3-/4-})) added to the electrolyte to study electron transfer kinetics at the electrode surface. |

| Data Fitting Software | Software used to fit the obtained EIS data to an equivalent circuit model to extract quantitative parameters (e.g., resistances, capacitances). |

The relationships and workflow of a standard EIS experimental setup are visualized below.

Table 3: Summary of Key EIS Equations and Parameters

| Parameter | Symbol | Equation / Description | Notes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complex Impedance | (Z(\omega)) | (Z = \frac{E(\omega)}{I(\omega)} = Z{re} + jZ{im}) | Fundamental transfer function [1]. | ||||

| Impedance Magnitude | ( | Z | ) | ( | Z | = \sqrt{Z{re}^2 + Z{im}^2}) | - |

| Phase Angle | (\phi) | (\phi = \arctan(\frac{Z{im}}{Z{re}})) | - | ||||

| Radial Frequency | (\omega) | (\omega = 2\pi f) | (f) is frequency in Hz [1]. | ||||

| Resistor Impedance | (Z_R) | (Z_R = R) | Purely real, frequency-independent [1]. | ||||

| Capacitor Impedance | (Z_C) | (Z_C = \frac{1}{j\omega C}) | Purely imaginary, decreases with frequency [1]. | ||||

| Inductor Impedance | (Z_L) | (Z_L = j\omega L) | Purely imaginary, increases with frequency [1]. | ||||

| Solution Resistance | (R_s) | Found from high-frequency x-intercept on Nyquist plot. | Represents uncompensated electrolyte resistance. | ||||

| Charge Transfer Resistance | (R_{ct}) | Diameter of semicircle on Nyquist plot. | Related to the kinetics of the electron transfer reaction; higher (R_{ct}) indicates slower kinetics. |

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) is a powerful steady-state technique that utilizes small-signal analysis to probe relaxations over a wide frequency range, from less than 1 mHz to greater than 1 MHz [9]. In a typical EIS experiment, a small sinusoidal potential (or current) is applied to an electrochemical cell, and the resulting current (or voltage) response is measured [1]. For a linear system, the response signal is a sinusoid at the same frequency but shifted in phase [9]. The impedance, a more general circuit parameter than simple resistance, is then calculated from the ratio of the voltage to the current [1]. Unlike resistance, impedance accounts for phase shifts and frequency-dependent behavior, making it indispensable for characterizing complex electrochemical systems such as batteries, sensors, and corrosion processes [9] [10].

The raw EIS data, comprising magnitude and phase information across a frequency spectrum, are most commonly visualized through two types of plots: Nyquist plots and Bode plots. These representations are not merely different ways of looking at the same data; they offer complementary insights. The Nyquist plot provides an intuitive, consolidated view of the system's impedance, while the Bode plot preserves explicit frequency information, which is crucial for understanding the kinetics of electrochemical processes [9] [1]. Mastering the interpretation of these plots is a fundamental skill for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals using EIS to study interfacial properties, bio-recognition events, and material characteristics in applications ranging from biomedical diagnostics to battery development [9] [10].

Fundamental Principles of Nyquist and Bode Plots

The Nyquist Plot

A Nyquist plot is a parametric plot used to visualize the frequency response of a system. In the context of EIS, it represents the imaginary component of the impedance (-Zimag) plotted against the real component (Zreal) across a sweep of frequencies [9] [1]. Each point on the curve corresponds to the impedance at one specific frequency. In these plots, the radial frequency decreases from left to right, meaning high-frequency data appears on the left and low-frequency data on the right [9]. The impedance can also be represented as a vector whose length is the magnitude |Z| and whose angle with the real axis is the phase angle (Φ) [1]. A significant shortcoming of the standard Nyquist plot is that the frequency information for each data point is not directly visible, making it necessary to annotate characteristic frequencies (e.g., the top of a semicircle) for proper interpretation [11].

The Bode Plot

A Bode plot, in contrast, displays the impedance information across frequency in two separate graphs, preserving frequency as the primary axis [1]. It consists of:

- A magnitude plot: The decimal logarithm of the impedance magnitude (log |Z|) is plotted against the decimal logarithm of frequency (log f).

- A phase plot: The phase angle (Φ, in degrees) is plotted against the decimal logarithm of frequency (log f) [11] [9].

This dual-plot structure makes Bode plots particularly useful for identifying capacitive behavior and evaluating the frequency dependence of different electrochemical processes [9]. The magnitude plot directly shows how the system resists the flow of current at different excitation frequencies, while the phase plot reveals the delay between the applied voltage and the measured current.

Theoretical Foundation and Complementary Nature

Both plots originate from the same fundamental complex impedance expression. The impedance (Z) is represented as a complex number Z = Z' + jZ'', where Z' is the real part, Z'' is the imaginary part, and j is the imaginary unit [1]. The magnitude and phase are derived as:

The Nyquist and Bode plots are mathematically equivalent representations of this data [11]. The choice between them often depends on the research field's conventions and the specific information the researcher wishes to emphasize. Nyquist plots excel at visualizing the number and approximate time constants of different processes, while Bode plots are superior for understanding the frequency ranges over which these processes operate.

Data Presentation and Interpretation

Visualizing and Interpreting Nyquist Plots

In a Nyquist plot, the shape of the curve reveals key information about the electrochemical system. A common feature is one or more semicircular arcs. Each semicircle is characteristic of a single "time constant" in the system, often representing a parallel combination of a resistor and a capacitor in the equivalent circuit model [1]. The diameter of a semicircle along the real Z-axis corresponds to a resistance, such as the charge transfer resistance (Rct), which is a critical parameter in analyzing the kinetics of an electrochemical reaction [9]. At low frequencies, a rising linear section with a 45° slope often indicates a mass-transfer controlled process, known as Warburg impedance [9].

Table 1: Interpretation of Common Features in a Nyquist Plot

| Plot Feature | Physical Interpretation | Common Electrochemical Process |

|---|---|---|

| High-Frequency Intercept on Real Axis | The ohmic solution resistance (Rs) of the electrolyte [9]. | Uncompensated resistance between working and reference electrodes. |

| Semicircular Arc | A single time constant, representing a parallel combination of a resistance and a capacitance [1]. | Charge transfer resistance (Rct) at the electrode-electrolyte interface combined with the double-layer capacitance (Cdl). |

| Multiple Semicircles | Multiple time constants with distinct relaxation frequencies [1]. | Separate processes at different interfaces (e.g., grain boundary and bulk effects in solid-state batteries [10]). |

| Low-Frequency 45° Line | Warburg impedance (W), signifying a diffusion-controlled or mass-transfer limited process [9]. | Diffusion of redox species from the bulk solution to the electrode surface. |

Visualizing and Interpreting Bode Plots

Bode plots provide a more direct link to frequency, which is essential for understanding the kinetics of electrochemical processes. The magnitude plot shows how the system's impedance changes with frequency. A horizontal line indicates a purely resistive behavior, while a line with a constant negative slope (e.g., -1 in log-log scale) suggests a capacitive-dominated response [9]. The phase plot reveals the number of time constants present; a peak in the phase plot indicates a process with a specific relaxation frequency, and overlapping processes can be identified by broad or multiple peaks.

Table 2: Interpretation of Common Features in a Bode Plots

| Plot Feature | Physical Interpretation | Information Revealed |

|---|---|---|

| Magnitude Plot: High-Frequency Plateau | Dominated by ohmic resistance (Rs). | The value of the solution resistance. |

| Magnitude Plot: Linear Region with -1 Slope | Dominated by capacitive behavior. | Double-layer capacitance or other capacitive elements in the system. |

| Magnitude Plot: Low-Frequency Plateau | Dominated by the sum of Rs and Rct. | The total DC resistance of the system. |

| Phase Plot: Peak(s) | Time constant(s) of the system. | The number of distinct electrochemical processes and their characteristic frequencies. |

| Phase Plot at 45° | Can indicate the presence of Warburg impedance [9]. | Mass-transfer limitations are significant at that frequency. |

Experimental Protocols for EIS Measurement

Pre-Experimental Setup and Calibration

A successful EIS experiment requires meticulous preparation to ensure data quality and reliability.

- Instrumentation: Use a potentiostat/galvanostat equipped with an FRA (Frequency Response Analyzer) or a dedicated EIS spectrometer. Ensure the device is properly calibrated according to the manufacturer's specifications [1].

- Electrode System: Set up a standard three-electrode configuration (Working Electrode, Counter Electrode, Reference Electrode) for accurate potential control. Ensure the working electrode surface is clean, well-defined, and reproducible. For biosensing applications, the working electrode may be functionalized with a biorecognition element (e.g., antibody, enzyme, DNA probe) [9].

- Electrolyte: Use a stable, degassed electrolyte solution with sufficient conductivity. Eliminate dissolved oxygen if it interferes with the redox reaction of interest by purging with an inert gas like nitrogen or argon.

- Steady-State Establishment: A critical and often overlooked step is to ensure the electrochemical system is at a steady state before commencing measurements. Drift in the system due to adsorption, reaction product buildup, or temperature changes during the measurement can lead to inaccurate and distorted results [1].

Step-by-Step EIS Measurement Procedure

The following protocol outlines a standard procedure for acquiring EIS data.

- DC Potential/Bias Application: Apply the desired DC potential (for potentiostatic EIS) to the working electrode versus the reference electrode. This potential should be chosen based on the system under study, often at the open-circuit potential (OCP) or at a potential relevant to a specific redox reaction [9] [1].

- Stability Check: Monitor the current until it stabilizes, confirming the system has reached a steady state. This may take from minutes to hours.

- Frequency Parameter Setting:

- Select the frequency range. A broad range (e.g., 100 kHz to 10 mHz) is common, but it should cover the time constants of the processes of interest [9].

- Set the number of frequency points per decade (e.g., 10 points/decade) for adequate resolution.

- Define the AC excitation amplitude. A small sinusoidal potential of 1 to 10 mV is standard to ensure the system response is pseudo-linear [1].

- Data Acquisition: Initiate the frequency sweep, typically from high to low frequency. The instrument applies the AC potential at each frequency and measures the amplitude and phase shift of the resulting current response [1].

- Data Validation: Modern software often provides real-time plotting. Check the acquired data for signs of instability, such as significant scatter or open-ended semicircles in the Nyquist plot. It is good practice to measure a known equivalent circuit (e.g., from a test box) to validate the system's performance [11].

- Data Export: Export the raw data, which should include at minimum the frequency (

f), the real part of impedance (Z'), and the imaginary part of impedance (Z'').

Post-Measurement Data Processing

- Data Review: Visualize the data in both Nyquist and Bode formats to check for quality and consistency.

- Kramers-Kronig Validation (Optional but Recommended): Apply the Kramers-Kronig transforms to test the data for linearity, causality, and stability. Data that violates these criteria may be unreliable.

- Equivalent Circuit Modeling: Use specialized software (e.g., ZView, EC-Lab, equivalent circuit model fitters in Python/R) to fit the data to a physically meaningful equivalent circuit. The choice of circuit should be based on the physical and chemical properties of the system [9] [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting EIS experiments, particularly in the context of biosensing and battery research.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for EIS

| Item Name | Function/Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Potentiostat/Galvanostat with FRA | Core instrument for applying potential/current and measuring the high-precision, low-amplitude AC response. | Essential for all EIS measurements [11] [1]. |

| Three-Electrode Cell | Electrochemical cell comprising Working, Counter, and Reference electrodes for precise potential control. | Standard setup for accurate EIS in corrosion, battery, and biosensor studies [9] [1]. |

| Redox Probe | A well-characterized, reversible redox couple (e.g., [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻) added to the electrolyte. | Probes interfacial properties and charge transfer resistance; used to monitor surface modification and biorecognition events [9]. |

| Nanomaterials (NPs, CNTs, Nanowires) | Enhance signal by providing catalytic activity, increased surface area for immobilization, and faster electron transfer. | Critical for enhancing the sensitivity of impedimetric biosensors for pathogens, DNA, or biomarkers [9] [10]. |

| Biorecognition Elements | Molecules (antibodies, antigens, enzymes, aptamers, whole cells) that specifically bind to the target analyte. | The core of an impedimetric biosensor; binding events alter the interface, changing the impedance signal [9]. |

| Solid-State Electrolyte | A solid ion-conducting material (e.g., polymer, ceramic) that replaces liquid electrolytes. | Key material for EIS characterization in the development of solid-state batteries for energy density and safety [10]. |

| Equivalent Circuit Modeling Software | Software used to fit EIS data to an electrical circuit model to extract quantitative parameters (R, C, W). | Used for quantitative analysis of all EIS data to deconvolute contributions from different processes [1] [10]. |

Equivalent Circuit Modeling from Plots

The ultimate goal of EIS analysis is often to extract quantitative physical parameters from the Nyquist and Bode plots. This is achieved by fitting the data to an equivalent circuit model, which is an electrical circuit composed of passive elements (resistors R, capacitors C, inductors L, and specialized elements like the Warburg impedance W) that simulates the electrochemical processes [9] [1].

For a simple system exhibiting one time constant (e.g., a bare electrode in a redox probe solution), the Randles circuit is a common model. It consists of:

- Solution Resistance (

Rs) in series with... - A parallel combination of Charge Transfer Resistance (

Rct) and Double-Layer Capacitance (Cdl). - A Warburg element (

W) may be added in series withRctto model diffusion.

For more complex systems like solid-state batteries, the equivalent circuit can include multiple (RQ) elements in series, where Q is a constant phase element (CPE) used to account for surface inhomogeneity, each representing a different physical region or interface (e.g., bulk electrolyte, grain boundaries, electrode-electrolyte interfaces) [10].

The process involves:

- Hypothesis: Propose a circuit based on the physical structure of the system.

- Fitting: The software adjusts the circuit element values to achieve the best fit to the experimental data.

- Validation: The quality of the fit is assessed, and the physical reasonableness of the extracted parameters is evaluated. A good fit does not guarantee the model is correct, so physical insight is paramount.

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) is a powerful analytical technique used to characterize the physical and electrochemical properties of systems ranging from biosensors to energy storage devices [12]. The technique operates by applying a small amplitude sinusoidal potential or current excitation across a wide frequency range and analyzing the system's response [1] [13]. The interpretation of EIS data relies heavily on modeling the electrochemical system using equivalent electrical circuits composed of discrete components [14]. This application note details the essential electrical elements—resistors, capacitors, and the Constant Phase Element (CPE)—that form the building blocks of these equivalent circuit models, providing researchers in drug development and related fields with the foundational knowledge required for accurate EIS data interpretation.

Essential Circuit Elements in EIS Modeling

In equivalent circuit modeling, individual physical and electrochemical processes are represented by specific electrical components whose behavior can be mathematically described [14]. The table below summarizes the core components, their impedance, and their primary electrochemical significance.

Table 1: Essential Electrical Components for EIS Equivalent Circuit Modeling

| Component | Impedance Formula | Phase Angle | Electrochemical Significance | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resistor (R) | ( Z = R ) [1] | 0° [1] | Solution resistance (RΩ), Polarization resistance (Rp) [14] | Independent of frequency; current in phase with voltage [1] |

| Capacitor (C) | ( Z = \frac{1}{j\omega C} ) [1] [14] | -90° [1] | Double-layer capacitance (Cdl), Coating capacitance (Cc) [14] | Impedance decreases with frequency; current leads voltage [1] |

| Inductor (L) | ( Z = j\omega L ) [1] [14] | +90° [1] | Adsorption processes, measurement artifacts [14] | Impedance increases with frequency; current lags voltage [1] |

| Constant Phase Element (Q) | ( Z = \frac{1}{(j\omega)^n Y_0} ) [15] [14] | ( -\frac{n\pi}{2} ) (typically -90° to 0°) [14] | Surface heterogeneity, roughness, porous layers [15] [14] | Empirically models non-ideal capacitive behavior; ( n ) is a dispersion factor (0-1) [14] |

The Resistor

The resistor represents a system's pure opposition to current flow, with no phase shift between the applied voltage and the resulting current [1]. In electrochemical systems, two resistors are particularly significant. The ohmic resistance (RΩ) represents the uncompensated resistance between the working and reference electrodes, which is dependent on the electrolyte's conductivity and the cell's geometry [14]. The polarization resistance (Rp) models the resistance to charge transfer across the electrode-electrolyte interface at the corrosion potential and is directly related to reaction kinetics, such as the corrosion current via the Butler-Volmer equation [14].

The Capacitor

An ideal capacitor's impedance decreases as frequency increases [1]. In electrochemistry, the most common capacitor is the double-layer capacitance (Cdl), which models the charge separation at the electrode-electrolyte interface, where ions from the solution approach the electrode surface [14] [3]. Its value is influenced by electrode potential, temperature, ionic concentrations, and electrode roughness [14]. Another example is the coating capacitance (Cc), which can be used to monitor water uptake in protective coatings, as the ingress of water (high dielectric constant) significantly increases the measured capacitance [14].

The Constant Phase Element (CPE)

The Constant Phase Element is a non-ideal capacitive component used extensively to model the complexity of real electrochemical interfaces [15]. Its impedance is given by ( Z = 1/(Y0 (j\omega)^n) ), where ( Y0 ) is the CPE coefficient or admittance constant, and ( n ) is an empirical exponent [14]. The CPE describes a frequency-independent phase angle of ( -n \times 90^\circ ) [15].

The CPe behavior is attributed to surface heterogeneity, roughness, and variations in current or potential distribution [15]. The parameter ( n ) indicates the degree of deviation from ideal capacitive behavior:

- ( n = 1 ): The CPE behaves as an ideal capacitor.

- ( n = 0 ): The CPE acts as a pure resistor.

- ( n = 0.5 ): The CPE is equivalent to a Warburg element, modeling semi-infinite linear diffusion [14] [15].

The physical meaning of the CPE is often interpreted as a statistical distribution of time constants due to a structural or energetic inhomogeneity at the electrode interface [15]. It can also be modeled using circuits with time-varying component values, such as a resistor in series with an inductor whose value increases linearly with time, correlating with known time-varying properties in applications [15].

Experimental Protocols for EIS Measurement

Prerequisites and Measurement Setup

- Instrumentation: A potentiostat/galvanostat with Frequency Response Analyzer (FRA) capabilities [3] [13].

- Electrochemical Cell: A standard three-electrode configuration is recommended, comprising a Working Electrode (WE), a Counter Electrode (CE), and a Reference Electrode (RE) [3].

- Connections: Use shielded, low-noise cables. For high-impedance systems (e.g., coatings, biosensors), minimize stray capacitance by using short cables and a Faraday cage [16]. For low-impedance systems (e.g., batteries), minimize stray inductance by twisting current-carrying cables together and avoiding large wire loops [16].

- Software: Instrument control and data acquisition software (e.g., EC-Lab, NOVA) [14] [16].

Step-by-Step Measurement Procedure

- System Stabilization: Bring the electrochemical system to a steady state at the desired DC potential or current. Monitor the open circuit potential (OCP) or current until it stabilizes to ensure stationarity [13].

- Parameter Definition:

- Set the DC bias potential (for potentiostatic EIS) or DC current (for galvanostatic EIS) corresponding to the system's operating point [3] [13].

- Select a frequency range, typically from high frequency (100 kHz - 1 MHz) to low frequency (10 mHz - 1 Hz), spaced logarithmically (e.g., 10 points per decade) [3] [13].

- Choose a perturbation signal amplitude small enough to ensure pseudo-linearity. A common range is 1-10 mV RMS for potential perturbations [1] [13].

- Linearity Verification: Utilize quality indicators such as Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) to confirm that the system's response is linear. A THD below 5% is generally acceptable [13].

- Data Acquisition: Initiate the frequency sweep. The instrument applies the AC perturbation at each frequency, measures the amplitude and phase shift of the current (or voltage) response, and calculates the impedance [1] [3].

- Stationarity Check: Use the Non-Stationary Distortion (NSD) indicator to verify that the system did not drift during the measurement, particularly during the lengthy low-frequency segment [13].

- Data Validation: Apply the Kramers-Kronig relations to assess the data's causality, linearity, and stability [13].

Equivalent Circuit and Data Interpretation Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow for constructing an equivalent circuit and interpreting EIS data, using a common Randles circuit model as an example.

Diagram Title: EIS Data Analysis and Circuit Fitting Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for EIS Experiments

| Item | Function/Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Potentiostat/Galvanostat with FRA | Instrument for applying controlled potentials/currents and measuring the resulting response with high precision [3] [13]. | Foundational for all EIS measurements. |

| Faraday Cage | A grounded metallic enclosure that shields the electrochemical cell from external electromagnetic noise, crucial for high-impedance measurements [16]. | Biosensor development, coating analysis. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known reference potential for the working electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl, Saturated Calomel) [3]. | Essential for all 3-electrode setups to ensure accurate potential control. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | An electrochemically inert salt (e.g., KCl, KNO3) at high concentration to provide ionic conductivity and minimize solution resistance (Rs) [14]. | Fundamental for any aqueous or non-aqueous electrochemical experiment. |

| Redox Probe | A reversible redox couple (e.g., [Fe(CN)6]3-/4-, [Ru(NH3)6]3+) used to probe charge-transfer kinetics at the electrode interface [12]. | Characterizing electrode modification, studying reaction kinetics. |

| Equivalent Circuit Modeling Software | Software (e.g., ZView, EC-Lab's ZFit) used to fit experimental EIS data to an equivalent circuit model and extract parameters [2] [16]. | Data analysis for all EIS studies. |

Building Equivalent Circuit Models to Simulate Real-World Behavior

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) is a powerful, non-destructive analytical technique that investigates complex electrochemical systems by applying a small sinusoidal excitation signal and measuring the system's response across a frequency spectrum [1] [13]. A fundamental aspect of EIS analysis involves using Equivalent Circuit Models (ECMs) to interpret impedance data. These models represent physical electrochemical processes—such as charge transfer, double-layer charging, and diffusion—using an arrangement of passive electrical circuit elements like resistors, capacitors, and inductors [1] [17]. The primary strength of this approach is its ability to quantify key parameters (e.g., charge transfer resistance, double-layer capacitance) that define the properties and performance of materials and electrochemical interfaces, providing a bridge between measured data and physical interpretation [17].

The practice is grounded in the concept of a "pseudo-linear" system. While electrochemical cells are inherently non-linear, applying a very small amplitude alternating current (AC) perturbation—typically 1 to 10 mV—ensures the system's response is approximately linear around its operating point, thus validating the use of linear circuit theory for analysis [1] [18] [13]. Selecting an appropriate ECM requires a balance between model complexity and physical justification. The model must be complex enough to capture the essential electrochemical phenomena but avoid overfitting the data with elements that lack a physical basis in the system under study [19].

Common Equivalent Circuit Elements and Models

An ECM is constructed from fundamental elements whose individual impedance behaviors are well-defined. The core components and their impedance expressions are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Fundamental Circuit Elements Used in EIS Equivalent Circuit Modeling

| Component | Current vs. Voltage Relationship | Impedance (Z) | Physical Electrochemical Analogy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resistor (R) | E = I R | Z = R | Solution resistance, charge transfer resistance |

| Capacitor (C) | I = C dE/dt | Z = 1/(jωC) | Ideal double-layer capacitance |

| Inductor (L) | E = L di/dt | Z = jωL | Cable inductance, adsorbed intermediates |

| Constant Phase Element (CPE) | - | Z = 1/((jω)^α Q) | Non-ideal capacitance (surface roughness, porosity) |

| Warburg Element (W) | - | Z = σ(1-j)/√ω | Semi-infinite linear diffusion |

These elements are combined in series and parallel to create models that represent the behavior of real-world systems. Table 2 describes some of the most frequently encountered ECMs in electrochemical research.

Table 2: Common Equivalent Circuit Models and Their Applications

| Model Name / Diagram | Circuit Description | Typical Applications | Nyquist Plot Signature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Randles Circuit [17] | RΩ + (Cdl // Rct) | Simple electrode interface with charge-transfer control. | One depressed semicircle. |

| Randles with Warburg [17] | RΩ + (Cdl // (Rct + W)) | Systems with charge-transfer and diffusion control (batteries, sensors). | A semicircle followed by a 45° diagonal line. |

| Coated Metal / Two-Time-Constant [17] [19] | RΩ + (Cc // Rpo) + (Cdl // Rct) | Metal with an organic coating, or a battery with two electrodes. | Two overlapping or distinct semicircles. |

| Simple Coating Model [17] | RΩ + C | An undamaged, high-impedance coating on a metal. | A straight, vertical line (capacitive). |

The Constant Phase Element (CPE) is often used instead of an ideal capacitor to account for non-ideal behaviors such as surface roughness, porosity, or current distribution inhomogeneities [20] [17] [19]. The CPE's impedance is defined by two parameters: Q (magnitude) and α (exponent). An α value of 1 represents an ideal capacitor, while lower values indicate a deviation from ideal capacitive behavior, leading to a "depressed" semicircle in the Nyquist plot [20].

The Model Building and Fitting Workflow

Constructing and validating an ECM is a systematic process that requires careful attention to experimental conditions and data quality. The following workflow outlines the key stages.

Prerequisites: Ensuring Data Quality

Before fitting, verifying that the data meets the fundamental requirements for EIS analysis is imperative.

- Linearity: The system must respond linearly to the applied AC perturbation. This is achieved by using a sufficiently small excitation amplitude (e.g., 10 mV). Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) analysis is a quantitative method to check for non-linearity, with a THD threshold of 5% often considered acceptable [18] [13].

- Stationarity: The system must be at a steady state and not drift during the measurement, which can take hours. Non-Stationary Distortion (NSD) indicators can monitor this. Measurements on a commercial battery during discharge, for instance, show that data below 0.1 Hz can become invalid due to non-stationarity [13].

- Causality, Linearity, and Stability (Kramers-Kronig Relations): These relations are used to validate the quality of impedance data, checking if it is physically meaningful [13].

Protocol: Circuit Fitting and Parameter Extraction

Once quality data is acquired, the fitting procedure can begin.

- Step 1: Initial Circuit Hypothesis. Propose an initial ECM based on prior knowledge of the system's physical electrochemistry. For a simple electrode interface, start with a Randles circuit [17].

- Step 2: Numerical Fitting. Use software to perform non-linear least squares regression to find the ECM parameters that minimize the difference between the model and the data. Advanced statistical methods like Bayesian Inference (BI) are increasingly used as they provide parameter estimates with quantifiable uncertainty, helping to mitigate overfitting [19].

- Step 3: Fit and Physical Validation. Assess the fit quality visually (on Nyquist and Bode plots) and through error analysis (e.g., chi-squared values). Crucially, evaluate whether the extracted parameter values are physically plausible. For example, a solution resistance should typically be in the range of 1-100 Ω for many aqueous systems [19].

Advanced Considerations and Non-Ideal Behavior

While ECMs are highly useful, researchers must be aware of their limitations and the complexities of real-world systems.

Addressing the Linearity Paradox

Most real electrochemical systems are non-linear, yet EIS analysis requires a pseudo-linear response. Test circuits with diodes and transistors demonstrate that in non-linear systems, the measured impedance can depend on both the DC bias potential (EWE) and the AC modulation amplitude (Va) [18]. Therefore, a single impedance measurement is insufficient to characterize a non-linear system fully. The standard practice is to use a low modulation amplitude and perform measurements at multiple DC potentials to map the system's behavior across different operating conditions [18].

Moving Beyond Lumped ECMs with Physics-Based Modeling

Equivalent circuits are lumped models that sometimes cannot fully capture distributed or coupled physical processes. In such cases, physics-based modeling offers a more robust alternative. Platforms like COMSOL Multiphysics allow researchers to model the fundamental governing equations for:

- Adsorption-Desorption Dynamics: Changing surface coverage of adsorbed species during a reaction can introduce additional time constants, even causing low-frequency inductive loops in the impedance spectrum [20] [21].

- Mass Transport Limitations: In fuel cells, the contribution of gas diffusion to the impedance spectrum can be modeled and distinguished from charge-transfer kinetics, showing how these processes merge and dominate at different operating potentials [20].

- Electrode Surface Roughness: Explicitly modeling a rough electrode geometry (e.g., a Koch snowflake) can reproduce the "depressed" semicircles often observed in experiments, which are otherwise modeled empirically with a CPE [20].

Bayesian Assessment of ECM Suitability

A critical challenge is selecting the right model complexity. A 2024 study used Bayesian Inference to systematically assess three common corrosion ECMs [19]. The key findings were:

- ECMs can contain elements that the data cannot reliably support; Occam's razor should be applied to use simpler models where possible.

- Low-frequency data collection, which is time-consuming, can often be reduced without substantially compromising the accuracy of parameter extraction, thus expediting EIS acquisition [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for EIS Modeling

| Item | Function / Description | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Potentiostat/Galvanostat with EIS Capability | Instrument that applies precise potentials/currents and measures the cell's response. | Fundamental for all EIS data acquisition. |

| Three-Electrode Cell Setup | A standard configuration using Working, Counter, and Reference electrodes. | Ensures accurate control and measurement of the interfacial potential. |

| Standard Test Solutions (e.g., KCl) | Electrolyte with well-known and stable properties. | Used for validating instrument performance and ECMs on predictable systems. |

| ECM Fitting Software (e.g., DECiM, ZFit, Custom Code) | Software tools for constructing ECMs and performing complex non-linear regression fits to the data. | DECiM is an open-source option; ZFit is bundled in EC-Lab; custom scripts offer maximum flexibility [18] [22]. |

| Physics-Based Simulation Software (e.g., COMSOL) | Models impedance by solving underlying physical equations (mass transport, kinetics) rather than fitting circuit elements. | Used when ECMs are insufficient for capturing coupled phenomena like adsorption and diffusion [20]. |

Building equivalent circuit models is a critical skill for interpreting EIS data and extracting meaningful parameters from electrochemical systems. The process begins with acquiring high-quality, linear, and stationary data, followed by hypothesizing a physically justified circuit, and culminates in rigorous fitting and validation. While ECMs rooted in electrical analogs are immensely powerful, researchers must be cognizant of their limitations, particularly for highly non-ideal or non-linear systems. The field is advancing with the adoption of Bayesian statistical methods for model selection and uncertainty quantification, and with the integration of physics-based modeling to capture complex real-world effects that lie beyond the reach of simple resistor-capacitor networks. By understanding and applying these principles and protocols, researchers can reliably use EIS to deepen their understanding of material degradation, battery performance, sensor design, and other critical electrochemical technologies.

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) is a powerful analytical technique that provides critical insights into interfacial properties and processes by measuring a system's response to an applied alternating current (AC) or voltage across a wide frequency range [23] [24]. Its applications span corrosion studies, battery development, biosensors, and material characterization [23]. A fundamental aspect of interpreting EIS data lies in understanding the nature of the charge transfer process occurring at the electrode-electrolyte interface, broadly classified as Faradaic or Non-Faradaic [25] [26].

This application note delineates the distinctions between Faradaic and Non-Faradaic processes within the context of EIS measurements. It provides a structured comparison, detailed experimental protocols for both approaches, and guidance on selecting the appropriate measurement mode for specific research applications in drug development and diagnostic biosensing.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Differences

The core difference between Faradaic and Non-Faradaic processes lies in the presence or absence of sustained net charge transfer across the electrode-electrolyte interface.

Faradaic Processes

Faradaic processes involve charge transfer across the interface, leading to oxidation or reduction of electroactive species [26] [27]. These are governed by Faraday's law, where the amount of chemical reaction caused by current flow is proportional to the amount of electricity passed. In EIS, Faradaic processes are studied using a system that includes a redox probe like Ferrycianide/KFerrycianide in the electrolyte solution [25]. The impedance response provides information about the charge transfer resistance (Rct), which is sensitive to surface modifications and the presence of specific biomarkers [25] [24].

Non-Faradaic Processes

Non-Faradaic (or capacitive) processes involve charge storage at the interface without a net, sustained Faradaic current [26]. Here, the applied potential leads to the charging of the electrical double layer (like a capacitor) or ion adsorption/desorption, without causing permanent electrochemical reactions [25] [27]. The impedance response in Non-Faradaic EIS is dominated by changes in interfacial capacitance, making it suitable for label-free biosensing where the binding of a target biomolecule (e.g., an antibody-antigen interaction) alters the capacitive properties of the electrode surface [25] [28].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Faradaic and Non-Faradaic EIS Modes

| Feature | Faradaic EIS | Non-Faradaic EIS |

|---|---|---|

| Charge Transfer | Direct electron transfer across the interface (redox reactions) [26]. | No sustained Faradaic current; electrostatic charge accumulation [26]. |

| Primary Mechanism | Electron transfer to/from redox species in solution [25]. | Change in interfacial capacitance or charge storage [25]. |

| Key Measured Parameters | Charge transfer resistance (Rct), Warburg impedance (diffusion) [29] [24]. | Double-layer capacitance (Cdl), often modeled with a Constant Phase Element (CPE) [29]. |

| Typical Circuit Element | Resistance (R) and Warburg element (W) in the equivalent circuit [29]. | Capacitance (C) or Constant Phase Element (CPE) in the equivalent circuit [29]. |

| Detection Principle | Measures hindrance to a redox reaction caused by surface binding events [25]. | Measures changes in the dielectric properties or insulating layer at the electrode interface [25] [28]. |

| Common Applications | Detection of electroactive biomarkers (e.g., dopamine); battery electrode kinetics [25] [30]. | Label-free detection of biomolecules (e.g., proteins, antibodies); material capacitance studies [25] [28]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Faradaic EIS Measurements

This protocol is designed for detecting a specific biomarker, such as alpha-synuclein oligomers for Parkinson's disease research [25].

1. Electrode Preparation and Functionalization

- Materials: Gold disk working electrode, Pt wire counter electrode, Ag/AgCl reference electrode, alkanethiol solution (e.g., 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid), EDC/NHS crosslinking mixture, specific capture probe (e.g., aptamer or antibody) [25].

- Procedure:

- Clean the gold working electrode: Polish with alumina slurry (0.05 µm), rinse with deionized water, and sonicate in ethanol and water for 5 minutes each. Perform electrochemical cleaning in 0.5 M H₂SO₄ via cyclic voltammetry (CV) until a stable CV is obtained.

- Incubate the clean electrode in a 1 mM solution of 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid in ethanol for 12 hours to form a self-assembled monolayer (SAM).

- Rinse thoroughly with ethanol and deionized water to remove physically adsorbed thiols.

- Activate the carboxyl termini by immersing the electrode in a mixture of 0.4 M EDC and 0.1 M NHS in water for 1 hour.

- Rinse with water and incubate with the specific capture probe (e.g., 1 µM alpha-synuclein aptamer in PBS) for 2 hours. The aptamer/antibody covalently binds to the activated SAM.

- Rinse with PBS and block non-specific sites by incubating with 1 mM 6-mercapto-1-hexanol for 1 hour.

2. EIS Measurement in the Presence of Redox Probe

- Materials: Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, pH 7.4) containing 5 mM K₃[Fe(CN)₆]/K₄[Fe(CN)₆] (1:1 mixture) as a redox probe [25].

- Procedure:

- Place the functionalized working electrode, counter electrode, and reference electrode in the cell containing the redox probe solution.

- Use a potentiostat to apply a DC potential set to the formal potential of the redox couple (e.g., +0.22 V vs. Ag/AgCl for Ferrycianide) with a superimposed AC voltage amplitude of 10 mV.

- Measure the impedance spectrum over a frequency range of 0.1 Hz to 100 kHz, recording at 10 points per decade.

- Introduce the sample containing the target analyte (e.g., alpha-synuclein) and incubate for 15-30 minutes.

- Rinse gently to remove unbound analyte and repeat the EIS measurement under identical conditions.

- The binding of the target biomarker impedes electron transfer to the redox probe, resulting in an increase in the measured charge transfer resistance (Rct).

Protocol for Non-Faradaic EIS Measurements

This protocol is ideal for label-free detection of biomolecules in samples like tear fluid, where capacitive changes are monitored [28].

1. Electrode Preparation and Bio-functionalization

- Materials: Interdigitated microelectrodes (IDEs), specific antibody (e.g., for TNF-α or lipocalin-1), ethanolamine blocking solution, PBS [28].

- Procedure:

- Clean the IDEs with oxygen plasma for 2 minutes to activate the surface and ensure hydrophilicity.

- Silanize the surface by vapor deposition of (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) for 1 hour at 70°C to create amine-reactive groups.

- Functionalize the electrode by incubating with a solution of the specific capture antibody (e.g., 10 µg/mL in PBS) for 2 hours, allowing covalent bonding to the silane layer.

- Block non-specific binding sites by incubating with 1 M ethanolamine solution (pH 8.5) for 30 minutes.

- Rinse the functionalized IDE with PBS to prepare for measurement.

2. EIS Measurement without Redox Probe

- Materials: A low-ionic-strength buffer (e.g., 1 mM PBS) to enhance capacitive sensitivity [28].

- Procedure:

- Place a small droplet (e.g., 10 µL) of the low-ionic-strength buffer onto the functionalized IDE.

- Using a potentiostat, measure the impedance spectrum from 1 Hz to 1 MHz with an AC voltage amplitude of 10-25 mV at 0 V DC bias (open circuit potential can be used).

- Record the baseline spectrum.

- Carefully introduce the sample (e.g., tear fluid) to the IDE surface and incubate for 15 minutes to allow target antigen-antibody binding.

- Gently rinse with the measurement buffer to remove unbound material.

- Measure the impedance spectrum again under identical conditions.

- The binding of the target analyte (a large biomolecule) to the electrode surface alters the dielectric properties and thickness of the interfacial layer, leading to a measurable change in capacitance, typically observed as a shift in the imaginary part of the impedance at low frequencies.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Their Functions

| Reagent/Material | Function in EIS Experiment |

|---|---|

| Redox Probe (e.g., [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻) | Enables Faradaic EIS by providing a reversible electron transfer reaction at the working electrode. Changes in Rct are monitored [25]. |

| Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM) Reagents | Forms an organized, thin film on the electrode (e.g., gold). Provides functional groups (-COOH, -NH₂) for subsequent immobilization of biorecognition elements [25]. |

| Crosslinkers (EDC/NHS) | Activates carboxyl groups on the SAM, facilitating covalent immobilization of proteins (antibodies) or aminated DNA/RNA aptamers onto the electrode surface [25]. |

| Biorecognition Elements (Aptamers/Antibodies) | The core of biosensor specificity. Binds selectively to the target biomarker, altering the interfacial properties of the electrode [25] [28]. |

| Blocking Agents (e.g., BSA, Ethanolamine, MCH) | Passivates unreacted sites on the functionalized electrode surface to minimize non-specific adsorption of non-target molecules, ensuring signal fidelity [25]. |

| Interdigitated Electrodes (IDEs) | Microfabricated electrodes that maximize surface area and enhance sensitivity for capacitive/Non-Faradaic measurements in small sample volumes [25] [28]. |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Equivalent Circuit Modeling

EIS data is typically interpreted by fitting to an electrical equivalent circuit that models the physical processes at the electrode-electrolyte interface [29] [24].

- For Faradaic EIS: The Randles circuit is most common. It includes the solution resistance (Rs), the charge transfer resistance (Rct), the double-layer capacitance (Cdl), and the Warburg impedance (ZW), which models diffusion. The key parameter is Rct, which increases upon successful binding of the target analyte [24].

- For Non-Faradaic EIS: A simpler circuit omitting the Faradaic elements is used, often consisting of Rs in series with a parallel combination of a pore resistance (Rpore) and a Constant Phase Element (CPE). The CPE is used instead of an ideal capacitor to account for the non-ideal, frequency-dependent capacitive behavior of real-world, heterogeneous surfaces [29]. The change in CPE parameters indicates successful binding.

Data Representation

Data is commonly visualized using:

- Nyquist Plot: Plots the negative imaginary impedance (-Z'') against the real impedance (Z'). A Faradaic system typically shows a semicircle (characterizing Rct/Cdl) at high frequencies followed by a 45° Warburg tail (diffusion) at low frequencies. A Non-Faradaic system may show a more vertical line, indicative of capacitive behavior [29] [24].

- Bode Plot: Shows impedance modulus |Z| and phase angle (δ) as a function of frequency, providing a complementary view [29].

The choice between Faradaic and Non-Faradaic EIS is application-dependent. Faradaic EIS is preferred when high specificity for an electroactive analyte is needed or when using a well-defined redox probe to quantify surface modifications, such as in the detection of dopamine or alpha-synuclein in neurological disease research [25]. Non-Faradaic EIS offers a label-free, often simpler approach ideal for detecting non-electroactive proteins, hormones, and for point-of-care diagnostics where minimal sample preparation is crucial, as demonstrated in tear fluid analysis for diseases like cancer, Alzheimer's, and Parkinson's [28].

In conclusion, understanding the fundamental distinctions between these two modes is essential for designing effective EIS-based biosensors. Faradaic processes provide information on charge-transfer resistance linked to redox reactions, while Non-Faradaic processes reveal capacitive changes at the interface. The selection hinges on the nature of the target analyte, the required sensitivity, and the desired simplicity of the assay protocol. As EIS technology advances, including its use in operando battery studies [31] and advanced impedance techniques [30], its role in diagnostic and therapeutic development is poised to expand significantly.

EIS in Practice: Techniques and Breakthroughs in Biomedical Research

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) is a powerful analytical technique that provides critical insights into the properties of electrochemical systems by measuring their impedance across a range of frequencies [3]. Within pharmaceutical development, EIS serves as an indispensable tool for characterizing drug-delivery mechanisms, biosensor interfaces, and biophysical properties of cellular membranes. The reliability of EIS data, however, is profoundly dependent on appropriate instrument selection and meticulous experimental configuration. This application note provides detailed protocols for selecting potentiostat systems and implementing optimal electrode configurations to ensure the generation of high-fidelity, reproducible EIS data suitable for rigorous scientific research.

Technical Specifications of Potentiostats for EIS

Selecting a potentiostat with specifications matched to your experimental needs is foundational to a successful EIS study. Key performance metrics include frequency range, current resolution, and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) accuracy. The table below summarizes the specifications of several research-grade potentiostats capable of EIS measurements.

Table 1: Comparison of Potentiostat Specifications for EIS Applications

| Model | Max Frequency for EIS | Min Current Resolution | Potential Range | Current Range | EIS Accuracy Verification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gamry Interface 1010E [32] | 2 MHz | 3.3 fA | ±12 V | ±1 A | Accuracy Contour Plots provided |

| PalmSens EmStat4S HR [33] | 200 kHz | 9.2 pA (on 100 nA range) | ±6 V | ±200 mA | Accuracy Contour Plots provided |

| Solartron Analytical 1287A [34] | 1 MHz (with 1260A FRA) | 1 pA | ±14.5 V (Polarization) | ±2 A | High-accuracy DVMs and patented conversion technique |

Beyond the specifications in Table 1, considerations should include:

- Floating Measurements: Essential for grounded setups like autoclaves or pipelines, a feature available in the Gamry Interface 1010E and Solartron 1287A [32] [34].

- Software and Control: All mentioned systems come with sophisticated software for experiment control and data analysis, with some offering scripting capabilities (e.g., Gamry's eChemAC Toolkit, PalmSens' MethodSCRIPT) for advanced customization and automation [32] [33].

Fundamentals of EIS and Electrode Configurations

Core EIS Theory

EIS operates on the application of a sinusoidal potential (or current) to an electrochemical cell and analysis of the resulting current (or potential) response [3]. The applied potential is described by:

( v(t) = V_o \sin(ωt) )

where ( V_o ) is the amplitude and ( ω ) is the angular frequency. The system's response is a current signal shifted by a phase angle (φ):

( i(t) = I_o \sin(ωt - φ) )

The impedance (Z) is a complex number with a real (Z') and imaginary (Z'') component, calculated as ( Z(ω) = v(t)/i(t) ) and represented as ( Z(ω) = Z' + jZ'' ) [3] [30]. Data is typically visualized using a Nyquist plot ( -Z'' vs. Z' ) or a Bode plot ( |Z| and φ vs. frequency ) [3].

Electrode Configuration Selection

The choice of electrode configuration is critical and depends on the system under study and the information required.

- Two-Electrode Configuration: Used for studying complete cells, such as batteries [35] or characterization of bulk electrolyte properties. The working and counter electrode leads are connected to the two poles of the cell. This configuration is simple but convolutes the responses of both electrodes.

- Three-Electrode Configuration (Recommended for most interfacial studies): This is the standard configuration for isolating the processes at the working electrode (WE) surface, which is critical in sensor development and corrosion studies [32] [3]. It introduces a reference electrode (RE) to provide a stable potential reference for the WE, while the counter electrode (CE) completes the current path.

- Four-Electrode Configuration: Employed when measuring solutions with high resistivity or to eliminate the impact of lead resistance, as it uses separate pairs of electrodes for current application and potential sensing [34].

Diagram: Workflow for Potentiostat and Electrode Configuration Selection

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Three-Electrode EIS

Research Reagent and Material Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for a Three-Electrode EIS Experiment

| Item | Function / Rationale | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Potentiostat with FRA | Applies potential perturbation and measures current response. | See Table 1 for system options. |

| Faraday Cage | Electrically shielded enclosure to block external electromagnetic noise. | Gamry Instruments offers accessory cages [32]. |

| Electrochemical Cell | Container for the electrolyte and electrodes. | Glass cell, or Flat Cell Kit (e.g., Solartron K0235) [34]. |

| Working Electrode (WE) | Electrode at which the reaction of interest occurs. | Glassy Carbon, Gold, or Platinum disk electrode (e.g., 3 mm diameter). |

| Reference Electrode (RE) | Provides a stable, known potential for the WE. | Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE) or Ag/AgCl (3 M KCl). |

| Counter Electrode (CE) | Completes the circuit, allowing current to flow. | Platinum wire or mesh. |

| Electrolyte Solution | Conducting medium containing the analyte. | Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) or other relevant buffer. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

System Setup and Connection

- Place the electrochemical cell inside the Faraday cage.

- Fill the cell with the electrolyte solution. If studying an analyte, ensure it is dissolved at the desired concentration.

- Polish the working electrode (if solid) sequentially with finer grades of alumina slurry (e.g., 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm) on a microcloth, then rinse thoroughly with deionized water.

- Insert the clean working, reference, and counter electrodes into the cell, ensuring they are immersed and not touching each other.

- Connect the electrode leads from the potentiostat to the corresponding electrodes using high-quality, shielded cables. The working electrode connection is the most sensitive and must be secure.

Initial Potentiostat Configuration

- Open the controlling software on the computer.

- Initialize the potentiostat and allow it to thermally stabilize for the time recommended by the manufacturer (typically 15-30 minutes).

- Check the open circuit potential (OCP) of the system. Allow the potential to stabilize to a steady value (e.g., drift < 2 mV/min). This stable OCP will often be used as the DC bias potential for the EIS measurement.

Parameter Setting and EIS Experiment Execution

- Navigate to the EIS experiment setup in the software.

- Set DC Bias Potential: Input the stabilized OCP value.

- Set AC Amplitude: Choose a sufficiently small amplitude to ensure a linear system response, typically 10 mV for non-biological systems. For sensitive systems like biological layers, 5 mV may be more appropriate.

- Set Frequency Range: A broad range from 100 kHz (or the maximum of your instrument) down to 100 mHz (or 10 mHz for slower processes) is a common starting point.

- Set Points per Decade: 10 points per decade provides a good balance of resolution and measurement time.

- Run the experiment. The software will automatically step through the frequencies and record the impedance data.

Data Quality Validation and Post-Measurement

- Visual Inspection: Immediately plot the acquired data in a Nyquist format. Look for signs of obvious noise or instability, such as severe scatter in the low-frequency data.

- Kramers-Kronig Test: Use the built-in software tool (available in advanced packages like Gamry's) to validate the stability, linearity, and causality of the data [32].

- Data Saving: Save the data in a secure location, noting all experimental conditions (electrode types, electrolyte, temperature, etc.) in the file metadata.

- Post-experiment: Clean the working electrode and reference electrode according to standard procedures to prevent contamination.

Diagram: Signal Flow in a Three-Electrode EIS Potentiostatic Measurement

Troubleshooting and Best Practices

Avoiding Common Artifacts

- High-Frequency Artifacts in 3-Electrode Setup: As highlighted in recent battery research, three-electrode configurations can be prone to high-frequency artifacts that are not present in two-electrode data [35]. These can manifest as an unexpected additional arc in the Nyquist plot. To mitigate this, ensure the reference electrode is placed correctly (close to the working electrode but not obstructing current lines) and has a sufficiently low impedance itself.

- Inductive Loops from Cables: Long, unshielded, or coiled cables can introduce inductive artifacts, which appear as arcs in the negative -Z'' region of the Nyquist plot. Use short, high-quality shielded cables and keep them straight.