Electrochemical Detection Techniques: A Comparative Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of modern electrochemical detection techniques, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical science.

Electrochemical Detection Techniques: A Comparative Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of modern electrochemical detection techniques, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical science. It explores the foundational principles of voltammetry, amperometry, potentiometry, and impedance spectroscopy, detailing their specific applications in critical areas such as biomarker detection for cancer, pathogen identification for infectious diseases, and therapeutic drug monitoring. The content further addresses common troubleshooting and optimization strategies to enhance sensor performance and longevity, and concludes with a rigorous validation framework comparing electrochemical methods against traditional analytical techniques, highlighting their advantages in sensitivity, cost, and suitability for point-of-care diagnostics.

Core Principles and Techniques of Electrochemical Sensing

Electrochemical detection techniques are grounded in the core principles of oxidation and reduction reactions, which form the basis for generating quantifiable analytical signals. These processes involve the transfer of electrons between an electrode surface and chemical species in solution, providing the foundation for a wide range of sensing applications across biomedical, pharmaceutical, and environmental fields. The measurable signals derived from these electron transfer events enable researchers to detect and quantify diverse analytes with remarkable sensitivity and specificity.

The growing significance of electrochemical sensors in research and drug development stems from their exceptional performance characteristics, including low detection limits, rapid response times, portability, and cost-effectiveness. As the global biosensors market expands—projected to grow from $33.16 billion in 2025 to $61.29 billion by 2034—understanding these fundamental processes becomes increasingly critical for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to leverage these technologies for advanced analytical applications [1].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of electrochemical detection techniques, focusing on their underlying mechanisms, operational parameters, and performance characteristics. By examining the fundamental relationship between oxidation-reduction processes and measurable signals across different sensing platforms, we aim to equip researchers with the knowledge needed to select appropriate methodologies for specific applications.

Core Principles: Electron Transfer and Signal Generation

Oxidation and Reduction Mechanisms

At the heart of all electrochemical detection systems are oxidation and reduction reactions, collectively termed redox reactions. Oxidation involves the loss of electrons from a species, while reduction involves the gain of electrons. These complementary processes occur simultaneously at electrode-solution interfaces when an appropriate potential is applied, establishing a continuous flow of electrons through the external circuit that serves as the primary measurable signal.

The working electrode serves as the platform where these redox reactions occur, with its surface properties fundamentally influencing the electron transfer kinetics. The reference electrode maintains a stable potential reference point, while the counter electrode completes the electrical circuit, allowing current to flow. This three-electrode configuration enables precise control and measurement of the electrochemical processes [2]. The nature of the electron transfer varies significantly between inner-sphere and outer-sphere redox markers, with inner-sphere mechanisms (e.g., with dopamine or ferricyanide) demonstrating high sensitivity to electrode surface chemistry and modification, while outer-sphere mechanisms (e.g., with hexaammineruthenium) are relatively insensitive to surface properties [3].

Signal Transduction Pathways

Electrochemical sensors convert recognition events into measurable electrical signals through various transduction mechanisms. Current-based signals arise directly from the flow of electrons during redox reactions, with the magnitude proportional to analyte concentration. Potential-based measurements reflect the thermodynamic favorability of redox reactions under equilibrium conditions. Impedance-based signals monitor changes in the electrical properties of the electrode-electrolyte interface, often without Faraday processes.

The signaling mechanism in conducting polymer-based sensors exemplifies this transduction principle, where the polymer serves as both sensing element and signal transducer simultaneously. Changes in the polymer's electrical properties (conductivity, redox activity, or capacitance) upon interaction with target analytes provide the detectable signal, simplifying sensor design while maintaining high sensitivity [4]. Nanomaterial-modified electrodes significantly enhance these signal transduction processes by providing increased surface area, improved electron transfer kinetics, and additional catalytic activity [5].

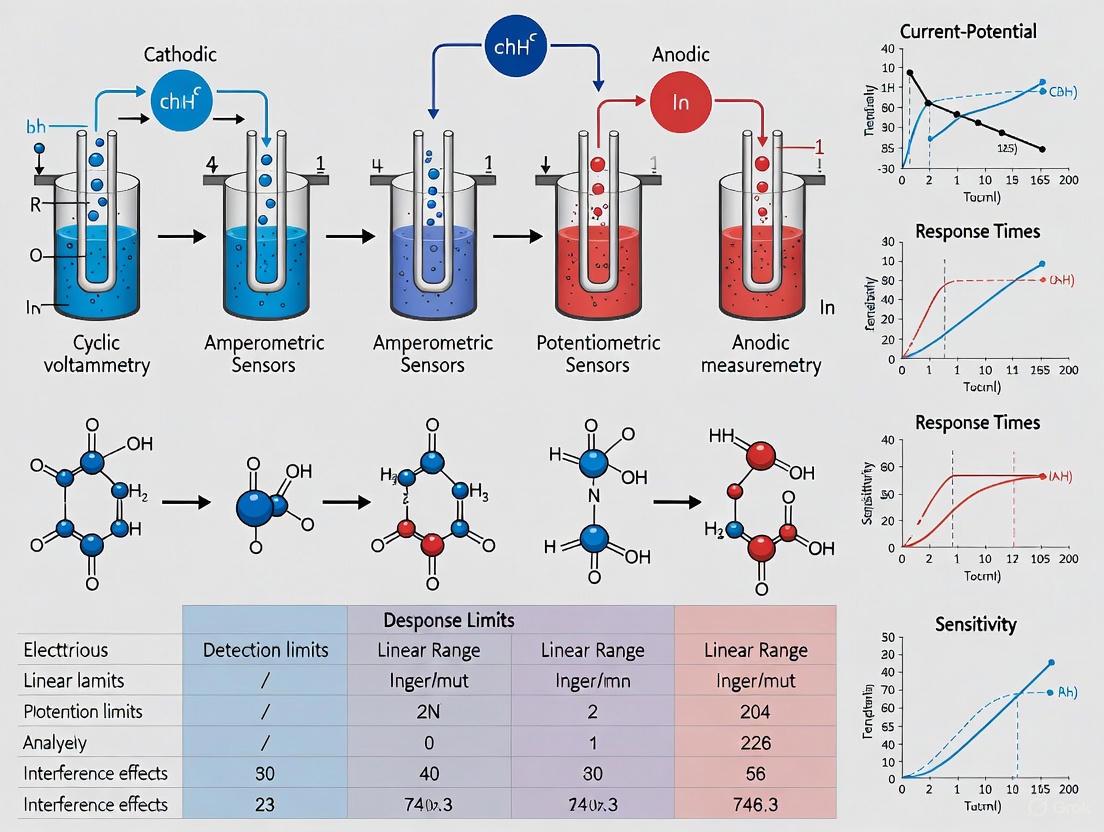

Figure 1: Fundamental electrochemical processes showing the relationship between oxidation-reduction reactions at electrode interfaces and the generation of measurable signals in a three-electrode system.

Comparison of Electrochemical Detection Techniques

Electrochemical detection methodologies vary significantly in their operational principles, sensitivity, and applicability to different analytical challenges. The table below provides a systematic comparison of the primary techniques employed in modern electrochemical sensors.

Table 1: Performance comparison of major electrochemical detection techniques

| Technique | Detection Principle | Measured Signal | Detection Limits | Key Advantages | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voltammetry (Cyclic, Differential Pulse) | Current measurement during controlled potential variation | Faradaic current | Nanomolar range (e.g., 2.5 nM for dopamine) [3] | High sensitivity, rich chemical information, qualitative & quantitative analysis | Neurotransmitter detection, heavy metal analysis, drug monitoring |

| Amperometry | Current measurement at fixed potential | Faradaic current | Piconanomolar range with nanomaterial enhancement | Continuous monitoring, real-time measurement, excellent temporal resolution | Biosensing, enzyme kinetics, gas detection |

| Impedance Spectroscopy | Response to AC potential perturbation | Impedance (Z) and phase shift | Low concentration detection via interfacial changes | Label-free detection, minimal sample perturbation, surface characterization | Affinity biosensing, corrosion studies, membrane characterization |

| Potentiometry | Potential measurement at zero current | Equilibrium potential | Micromolar to millimolar range | Simple instrumentation, wide concentration range, pH sensitivity | Ion-selective electrodes, pH sensing, clinical analyzers |

The selection of an appropriate detection technique depends on multiple factors, including the target analyte's electrochemical activity, required sensitivity, matrix complexity, and desired measurement speed. Voltammetric techniques, particularly differential pulse voltammetry, offer superior sensitivity for trace analysis, with detection limits reaching nanomolar concentrations for neurotransmitters like dopamine when using nanoparticle-modified electrodes [3]. In contrast, impedance-based methods provide exceptional capability for monitoring binding events and interfacial properties without redox labels, making them ideal for affinity-based biosensors.

The growing trend toward miniaturization and point-of-care testing has driven the development of screen-printed electrodes and portable systems that maintain analytical performance while offering operational convenience. These advancements are particularly valuable for therapeutic drug monitoring, environmental field testing, and rapid diagnostic applications where laboratory-based instrumentation is impractical [3].

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Voltammetric Detection of Heavy Metals

Principle: This protocol utilizes differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) for the sensitive detection of heavy metal ions (e.g., Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺, Hg²⁺) in environmental samples, leveraging the preconcentration and stripping analysis principle [5].

Materials and Reagents:

- Working Electrode: Glassy carbon electrode modified with bismuth film or mercury film

- Reference Electrode: Ag/AgCl (3M KCl)

- Counter Electrode: Platinum wire

- Supporting Electrolyte: Acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.5)

- Standard Solutions: 1000 ppm stock solutions of target heavy metals

- Deoxygenating Gas: High-purity nitrogen or argon

Procedure:

- Electrode Modification: Polish the glassy carbon electrode with 0.05 μm alumina slurry, rinse with distilled water, and electrodeposit bismuth film at -1.0 V for 120 seconds in a solution containing 400 ppm Bi³⁺.

- Sample Preparation: Mix 10 mL of water sample with 10 mL of acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.5). Add 100 μL of Bi³⁺ stock solution (1000 ppm) if using in-situ bismuth film formation.

- Deoxygenation: Purge the solution with nitrogen for 300 seconds to remove dissolved oxygen.

- Preconcentration Step: Apply a deposition potential of -1.2 V while stirring for 120 seconds to reduce and accumulate metal ions on the electrode surface.

- Equilibration: Stop stirring and allow the solution to become quiescent for 15 seconds.

- Stripping Scan: Record the DP voltammogram from -1.2 V to 0 V using a pulse amplitude of 50 mV, pulse width of 50 ms, and scan rate of 20 mV/s.

- Cleaning Step: Apply a cleaning potential of +0.3 V for 30 seconds to remove residual metals from the electrode.

- Calibration: Perform standard addition with known concentrations of target metals for quantification.

Data Analysis: Identify heavy metals based on their characteristic peak potentials (Pb²⁺: ~ -0.5 V, Cd²⁺: ~ -0.7 V, Hg²⁺: ~ +0.2 V). Quantify concentrations using peak current versus concentration calibration curves.

Enzyme-Free Organophosphorus Pesticide Detection

Principle: This protocol describes the voltammetric detection of organophosphorus (OP) compounds using molecularly imprinted polymers or metal oxide nanomaterials, eliminating enzyme stability issues associated with conventional biosensors [6].

Materials and Reagents:

- Working Electrode: Screen-printed carbon electrode modified with ZrO₂ nanoparticles or molecularly imprinted polymer

- Reference Electrode: Ag/AgCl (screen-printed)

- Counter Electrode: Carbon (screen-printed)

- Supporting Electrolyte: Phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.0)

- Standard Solutions: Chlorpyrifos, malathion, or other OP compounds in acetonitrile

- Modification Materials: ZrO₂ nanoparticles, graphene oxide, conductive polymers

Procedure:

- Electrode Modification: Drop-cast 5 μL of ZrO₂ nanoparticle dispersion (2 mg/mL in DMF) onto the working electrode surface and dry at 60°C for 30 minutes.

- Sample Preparation: Extract OP compounds from environmental samples using solid-phase extraction. Reconstitute in acetonitrile and dilute with phosphate buffer.

- Incubation: Immerse the modified electrode in the sample solution for 300 seconds to allow OP compound adsorption.

- Electrochemical Measurement: Transfer the electrode to a clean electrochemical cell containing phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.0).

- Voltammetric Scan: Record square wave voltammograms from +0.8 V to -0.5 V using a frequency of 25 Hz, amplitude of 25 mV, and step potential of 5 mV.

- Control Measurement: Perform identical measurements in blank solution to establish baseline.

Data Analysis: Monitor the decrease in oxidation current of specific redox probes (e.g., ferricyanide) or appearance of new peaks corresponding to OP compound oxidation. Quantify concentration using standard addition methods.

Nanoparticle-Enhanced Dopamine Sensing

Principle: This protocol demonstrates the enhanced detection of dopamine using gold nanoparticle-modified boron-doped diamond electrodes, leveraging the catalytic properties of nanomaterials for improved sensitivity and selectivity [3].

Materials and Reagents:

- Working Electrode: Boron-doped diamond electrode (BDDE) modified with gold nanoparticles

- Reference Electrode: Ag/AgCl (3M KCl)

- Counter Electrode: Platinum wire

- Supporting Electrolyte: Phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- Standard Solutions: Dopamine hydrochloride (10 mM stock in 0.1 M HClO₄)

- Modification Solutions: HAuCl₄ (1 mM in 0.1 M KCl)

Procedure:

- Electrode Modification: Electrochemically deposit gold nanoparticles on BDDE by cycling potential from -0.2 V to +1.0 V (5 cycles) at 50 mV/s in HAuCl₄ solution.

- Electrode Characterization: Characterize modified electrode in 1 mM K₃[Fe(CN)₆] using cyclic voltammetry (0.1 V to 0.5 V, 50 mV/s).

- Sample Preparation: Dilute dopamine stock solution in phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4) to desired concentrations.

- Standard Addition: Transfer 10 mL of sample to electrochemical cell, deoxygenate with nitrogen for 180 seconds.

- Differential Pulse Voltammetry: Record DP voltammograms from 0 V to +0.5 V using pulse amplitude of 50 mV, pulse width of 50 ms, scan rate of 20 mV/s.

- Selectivity Testing: Perform control experiments with potential interferents (ascorbic acid, uric acid) at physiological concentrations.

Data Analysis: Measure dopamine oxidation peak at approximately +0.25 V. Construct calibration curve of peak current versus dopamine concentration. Calculate detection limit using 3σ/slope method.

Figure 2: Generalized experimental workflow for electrochemical detection methodologies, showing the sequential steps from sample collection to result interpretation, with decision points for method selection based on target analyte characteristics.

Advanced Materials and Electrode Modifications

The performance of electrochemical sensors is profoundly influenced by electrode surface modifications, which enhance sensitivity, selectivity, and stability. Nanomaterials and conducting polymers have emerged as particularly effective modification agents due to their unique electrical and structural properties.

Table 2: Key research reagents and materials for electrochemical sensor development

| Material Category | Specific Examples | Key Functions | Performance Enhancements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Nanomaterials | SWCNTs, MWCNTs, Graphene, Boron-doped diamond | High surface area, excellent conductivity, wide potential window | Enhanced electron transfer, antifouling properties, catalytic activity [5] [3] |

| Metal Nanoparticles | Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), Silver nanoparticles, Bismuth nanoparticles | Electrocatalysis, signal amplification, large surface-to-volume ratio | Decreased detection limits, improved reversibility, higher sensitivity [3] |

| Conducting Polymers | Polypyrrole (PPy), Polyaniline (PANI), PEDOT | Intrinsic conductivity, redox activity, biocompatibility, 3D structure | Increased active sites, rapid ion transmission, efficient electron transfer [7] [2] |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks | ZIF-8, UiO-66, MIL-101 | Ultrahigh porosity, tunable functionality, molecular sieving | Selective preconcentration, size exclusion, enhanced stability [5] |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers | Polymer matrices with template-shaped cavities | Synthetic recognition elements, biomimetic specificity | Enzyme-free operation, high stability, selective binding sites [6] |

The strategic selection and combination of these advanced materials enable researchers to tailor electrode properties for specific analytical challenges. Gold nanoparticles, for instance, have demonstrated remarkable catalytic effects when modifying boron-doped diamond electrodes, achieving dopamine detection limits of 2.5 nM compared to unmodified electrodes [3]. Similarly, conducting polymers like polypyrrole and polyaniline provide not only excellent conductivity but also unique three-dimensional structures that increase active sites and facilitate rapid ion transmission during electrochemical reactions [2].

The integration of multiple nanomaterials in composite structures often yields synergistic effects that surpass the performance of individual components. For example, combining carbon nanotubes with metal nanoparticles or conducting polymers creates hierarchical structures that leverage the advantages of each material class, resulting in sensors with exceptional sensitivity, stability, and selectivity [5].

Electrochemical detection techniques continue to evolve, driven by advances in fundamental understanding of electron transfer processes and the development of novel sensing materials. The core principles of oxidation and reduction provide a robust foundation for generating measurable signals across diverse applications, from environmental monitoring to clinical diagnostics and pharmaceutical analysis.

Future developments in electrochemical sensing are likely to focus on several key areas. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning for data analysis will enhance pattern recognition capabilities and improve the accuracy of multi-analyte detection systems [1]. The growing emphasis on point-of-care testing and wearable sensors will drive innovations in miniaturization, flexibility, and wireless connectivity, enabling real-time health monitoring and environmental surveillance [8]. Additionally, the development of increasingly sophisticated nanomaterials and biomimetic recognition elements will address current challenges in selectivity, stability, and multiplexing capability.

As these technologies advance, the fundamental electrochemical processes of oxidation, reduction, and signal generation will remain central to sensor operation, providing the critical link between molecular recognition and analytical measurement. Researchers and drug development professionals who master these fundamental principles will be well-positioned to leverage the full potential of electrochemical detection in their scientific endeavors and product development initiatives.

Voltammetry encompasses a suite of electrochemical techniques widely employed to study electroactive species by measuring current as a function of applied potential. These methods are indispensable in pharmaceutical research, environmental monitoring, and materials science for quantifying analytes, investigating electron transfer kinetics, and understanding redox mechanisms [9] [10]. The selection of a specific voltammetric technique is crucial, as it directly influences the sensitivity, selectivity, and temporal resolution of an analysis, particularly in complex matrices like biological fluids and pharmaceutical formulations [11] [9].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of three foundational voltammetric methods: Cyclic Voltammetry (CV), Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV), and Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV). Each technique possesses unique waveform characteristics, data acquisition protocols, and areas of application. The objective is to equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the knowledge to select the most appropriate method for their specific analytical challenges, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols.

Principles and Waveform Characteristics

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV)

Principle: CV applies a linear potential sweep between two set limits (initial and final potentials) and reverses the sweep direction upon reaching each limit, creating a cyclic triangular waveform [12]. The resulting current response is plotted against the applied potential to form a cyclic voltammogram, which provides information on the thermodynamics of redox processes, reaction kinetics, and coupled chemical reactions [12].

Waveform: The potential is scanned at a constant rate (scan rate, V/s) from a starting potential to an upper potential, then back to a lower potential, and often finally back to the starting potential [12] [13]. The key parameters are the scan rate and the vertex potentials.

Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV)

Principle: DPV is a pulse technique designed to minimize the contribution of non-Faradaic (charging) current, thereby enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio for the Faradaic (redox) current [13] [14]. Small potential pulses are superimposed on a linear baseline potential ramp. The current is sampled twice for each pulse: just before the pulse application and at the end of the pulse. The difference between these two current measurements is plotted against the baseline potential, producing a peak-shaped voltammogram where the peak current is proportional to analyte concentration [13].

Waveform: The waveform consists of a series of pulses of fixed height (typically ~100 mV) and duration. The baseline potential increases linearly with each pulse. Critical parameters include pulse height, pulse width, and the time interval during which current is sampled [13].

Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV)

Principle: SWV combines the advantages of pulse techniques with speed [15]. A symmetrical square wave is superimposed onto a staircase potential ramp. The current is measured at the end of both the forward (positive-going) and reverse (negative-going) pulses of each square-wave cycle. The difference between the forward and reverse currents is plotted against the applied potential, yielding a peak-shaped output. This differential current measurement effectively suppresses capacitive currents and can provide insights into the reversibility of the electrode reaction [14] [15].

Waveform: The waveform is defined by parameters such as the square-wave amplitude, step potential (of the staircase), and frequency. The high frequency of the square wave allows for very fast scans, making SWV one of the fastest voltammetric techniques [14].

The logical relationship between the core principles of these three techniques is summarized in the following diagram:

Comparative Performance Analysis

The choice between CV, DPV, and SWV involves trade-offs between sensitivity, speed, resolution, and the type of information required. The following table summarizes their key performance characteristics and optimal application ranges based on experimental data.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of cyclic, differential pulse, and square-wave voltammetry.

| Feature | Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Application | Mechanistic studies, reversibility assessment, kinetic analysis [12] | High-sensitivity quantitative analysis, trace-level detection [13] [14] | Fast, high-resolution quantitative analysis, trace-level detection [14] [15] |

| Sensitivity | Moderate (measures total current) [14] | High (minimizes capacitive current) [13] [14] | Very High (effectively rejects background) [14] [15] |

| Scan Speed | Slow to moderate (scan rate dependent) | Moderate | Very Fast (due to high-frequency pulses) [14] |

| Background Suppression | Poor | Excellent [13] [14] | Excellent [14] |

| Resolution | Good for separated reactions | Excellent for closely spaced redox peaks [14] | Superior for closely spaced redox peaks [14] |

| Kinetic Information | Provides rich kinetic and thermodynamic data [11] [12] | Limited | Provides information on reversibility [14] [15] |

| Optimal Electron Transfer Rate (kHET, s⁻¹) | ~0.5 - 70 [11] | Broad range, excellent for slow to moderate rates | ~5 - 120 (broad range, suitable for faster rates) [11] |

| Typical Detection Limit | Micromolar (µM) range | Nanomolar (nM) to picomolar (pM) range [9] [14] | Nanomolar (nM) to picomolar (pM) range [14] |

| Data Output Shape | Sigmoidal (for a surface-confined species) or peak (for diffusion-controlled) | Peak [13] | Peak [14] |

Quantitative data on the optimal working ranges for electron transfer rates further highlights the complementary nature of these techniques. For instance, in a study interrogating electron transfer rates of immobilized cytochrome c, CV was most applicable for rates of approximately 0.5 - 70 s⁻¹, while SWV was suitable for a broader range of 5 – 120 s⁻¹ [11].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Electrode Modification and Setup

A critical step in enhancing sensor performance is electrode modification. The following workflow is a generalized protocol for modifying a Carbon Paste Electrode (CPE) with nanomaterials, adapted from studies on fabricating highly sensitive sensors [16] [17].

Table 2: Key research reagents and materials for electrode modification.

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Graphite Powder | Conductive base material for the carbon paste electrode [16] [17] | Used in CPE and MoS2-CILPE preparation [16] [17] |

| Paraffin Oil | Binder for graphite powder to form a cohesive paste [16] [17] | Binder in CPE and nRGO-modified electrodes [16] [17] |

| Ionic Liquid (e.g., 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate) | Enhances conductivity and electron transfer rate [16] | Component in MoS2-CILPE for folic acid sensing [16] |

| Nanomaterial (e.g., MoS2, nRGO) | Increases active surface area, improves electrocatalysis, and enhances sensitivity/selectivity [16] [17] | MoS2 nanosheets for folic acid sensor [16]; nRGO for bumadizone sensor [17] |

| Britton-Robinson (BR) Buffer / Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS) | Supporting electrolyte; maintains pH and ionic strength [16] [17] [15] | PBS (pH 7.0) for folic acid detection [16]; BR buffer for bumadizone [17] |

Representative Experimental Procedures

A. Protocol for Drug Detection using DPV (e.g., Folic Acid) [16]

- Sensor Fabrication: Prepare a MoS₂-modified carbon ionic liquid paste electrode (MoS₂-CILPE) by thoroughly mixing 0.04 g of MoS₂ nanosheets, 0.96 g graphite powder, and an appropriate amount of ionic liquid (1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate) and paraffin oil (30/70 w/w) in a mortar and pestle. Pack the resulting paste into a glass tube and insert a copper wire for electrical contact.

- Measurement: Place the MoS₂-CILPE (working electrode), a Pt wire (auxiliary electrode), and an Ag/AgCl reference electrode into a cell containing 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.0) as the supporting electrolyte.

- DPV Parameters: Use typical DPV parameters such as a pulse height of 100 mV, pulse width of 50 ms, and a step potential of 10 mV.

- Analysis: Record DPV curves after standard additions of the folic acid solution. Plot the peak current (typically around +0.7 V vs. Ag/AgCl) against concentration to build a calibration curve for quantifying unknown samples.

B. Protocol for Analysis in Complex Media using SWV (e.g., Blood Serum) [15]

- Electrode Selection: Use an edge-plane pyrolytic graphite electrode (EPGE) for its superior electrocatalytic properties.

- Sample Preparation: Dilute human blood serum in a phosphate buffer solution (pH 7.34, 0.1 mol/L). No further chemical treatment is required.

- SWV Parameters: Optimize SWV conditions (frequency, amplitude, step potential) to resolve the signals of uric acid, bilirubin, and albumin.

- Measurement: Immerse the EPGE in the diluted serum. After a brief equilibration, run the SWV scan. The voltammogram will show well-defined, separated peaks for each analyte, allowing for their characterization in a single experiment.

Applications in Pharmaceutical and Biological Analysis

The comparative advantages of CV, DPV, and SWV make them suited for different applications within drug development and bioanalysis.

Cyclic Voltammetry for Mechanistic Studies: CV is extensively used to understand the redox behavior and stability of drug molecules. For example, it can be employed to study the irreversible oxidation of serotonin, which helps explain its fouling propensity on electrodes [18]. It is also ideal for initial characterization to determine the formal reduction potential and reversibility of a new electroactive compound [12] [10].

Differential Pulse Voltammetry for Sensitive Quantification: DPV's low detection limits make it ideal for drug monitoring. It has been successfully used to determine folic acid in tablets and urine samples [16] and to detect anti-inflammatory drugs like bumadizone in pharmaceutical forms and biological fluids at nano-concentrations without preliminary separation [17]. Its ability to minimize background current is crucial for analyzing complex matrices.

Square-Wave Voltammetry for High-Throughput and Multi-Analyte Detection: The speed and sensitivity of SWV are advantageous for direct analysis in highly complex media. A key application is the simultaneous detection of uric acid, bilirubin, and albumin in human blood serum without electrode modification or sample pre-treatment [15]. SWV is also pivotal in advanced research, such as the development of rapid-pulse voltammetry (RPV) waveforms for simultaneous monitoring of neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine [18].

Cyclic, Differential Pulse, and Square-Wave Voltammetry are complementary techniques that form a powerful analytical toolkit. CV remains the primary method for exploratory mechanistic and kinetic studies. In contrast, DPV and SWV are the techniques of choice for high-sensitivity quantitative analysis, with SWV offering additional speed and resolution benefits.

The ongoing development of novel electrode materials, such as 2D transition metal dichalcogenides (e.g., MoS₂) and nano-reduced graphene oxide (nRGO), continues to push the detection limits and selectivity of all these methods [16] [17]. Furthermore, the emergence of machine-learning-guided optimization of voltammetric waveforms promises to unlock new levels of performance and selectivity, particularly for challenging analytes in complex biological environments [18]. This evolution ensures that voltammetry will maintain its critical role in advancing pharmaceutical research and bioanalytical science.

Amperometry is an electrochemical technique characterized by applying a constant potential to an electrochemical cell and measuring the resulting current as a function of time. This method is fundamental in analytical chemistry for detecting and quantifying various analytes, offering significant advantages for continuous monitoring applications in fields ranging from drug development to environmental analysis [19] [20].

Core Principle and Comparative Advantage

Amperometry falls under the broader category of electroanalytical methods, specifically distinguished by its operation at a fixed potential. This sets it apart from related techniques like voltammetry, where the potential is systematically varied, and potentiometry, where the potential is measured under conditions of zero current [19]. The core principle involves measuring the faradaic current generated by the oxidation or reduction of an electroactive species at the working electrode surface. This current is directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte in the bulk solution [21].

The technique's simplicity, high sensitivity, and fast response time make it particularly suitable for continuous, real-time monitoring [20]. Unlike batch methods that provide a single data point, amperometry can track concentration changes dynamically, offering a window into evolving chemical processes. This is invaluable for applications such as tracking drug pharmacokinetics, monitoring metabolic biomarkers, or detecting environmental pollutants [20] [22]. Furthermore, the method's compatibility with miniaturization and portable instrumentation underpins its use in point-of-care diagnostic devices, such as glucose biosensors for diabetes management [23].

Performance Comparison of Electrochemical Techniques

To objectively evaluate amperometry's performance, it is essential to compare it with other standard electrochemical and analytical methods. The following table summarizes key performance metrics based on experimental data from recent research for the detection of various analytes.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Detection Techniques

| Detection Method | Target Analyte | Linear Range | Detection Limit | Sensitivity | Key Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amperometry | Hydroxylamine [24] | 10–4000 µM | 0.47 µM | 408 μA mM⁻¹ cm⁻² | Environmental/Industrial Safety |

| Amperometry | Glucose [23] | 0.04–2.18 mM | 0.021 mM | 19.38 μA mM⁻¹ cm⁻² | Clinical Diagnostics (Biosensor) |

| Amperometry | Quercetin [25] | N/R | 1.22 × 10⁻⁷ mol L⁻¹ | N/R | Cosmetic/Pharmaceutical Analysis |

| Voltammetry (DPV) | Quercetin [25] | N/R | 5.64 × 10⁻⁸ mol L⁻¹ | N/R | Cosmetic/Pharmaceutical Analysis |

| Colorimetry | Hydrogen Sulfide (H₂S) [26] | Millimolar (mM) range | Micromolar (µM) range | N/R | Research - Physiological Solutions |

| Chromatography (HPLC) | Hydrogen Sulfide (H₂S) [26] | Micromolar (µM) range | Nanomolar (nM) range | N/R | Research - Physiological Solutions |

N/R: Not Reported in the cited source.

A direct comparison of techniques for quantifying hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) in simulated physiological solutions further highlights the relative performance of amperometry. Researchers found that while colorimetric and chromatographic methods quantified H₂S in the millimolar and micromolar ranges, respectively, electrochemical methods, including amperometry, were capable of quantification in the nanomolar and picomole ranges and were less time-consuming [26].

Experimental Protocols for Amperometric Sensing

The development of a functional amperometric sensor involves a multi-step process, from electrode modification to analytical validation. Below are detailed protocols for two distinct types of amperometric sensors: a material-based sensor for a small molecule and an immunosensor for a protein.

Protocol: Hydroxylamine Sensor using NiCo₂O₄ Nanoparticles

This protocol outlines the creation of a high-performance, enzyme-free sensor for toxic hydroxylamine (HYA) [24].

- 1. Synthesis of NiCo₂O₄ (NCO) Nanoparticles: Use a hydrothermal method. Dissolve 10 mmol of nickel(II) nitrate hexahydrate and 20 mmol of cobalt(II) nitrate hexahydrate in 60 mL of distilled water. Slowly add 0.25 g of urea to the solution with stirring. Transfer the mixture to a Teflon-lined autoclave and heat at 120°C for 6 hours. After cooling, collect the precipitate by centrifugation, wash with water and ethanol, and dry. Finally, calcine the product at 300°C for 2 hours [24].

- 2. Electrode Modification: Prepare a homogeneous ink by dispersing the synthesized NCO nanoparticles in a solvent (e.g., water or ethanol). Deposit a precise volume (e.g., 5-10 µL) of this ink onto a cleaned Fluorine-doped Tin Oxide (FTO) electrode surface and allow it to dry, resulting in the NCO@FTO working electrode [24].

- 3. Amperometric Measurement (Chronoamperometry): Use a standard three-electrode system with the NCO@FTO as the working electrode, a Ag/AgCl reference electrode, and a platinum wire auxiliary electrode. Apply a constant potential of 0.66 V vs. Ag/AgCl in a stirred solution. Upon successive additions of hydroxylamine standard solution, measure the steady-state current. The increase in current is proportional to the HYA concentration [24].

Protocol: SARS-CoV-2 S1 Protein Immunosensor

This protocol details a sensitive sandwich-type amperometric immunosensor for detecting a viral protein, demonstrating the technique's applicability in diagnostics [27].

- 1. Electrode Activation: Activate a Screen-Printed Carbon Electrode (SPCE) electrochemically by applying +0.9 V for 60 s in acetate buffer (pH 4.80). Then, chemically activate the surface by depositing a mixture of 50 mM EDC and 50 mM NHS (1:1 ratio) and incubating for 1 hour to activate carboxyl groups for antibody binding [27].

- 2. Antibody Immobilization and Assay Procedure:

- Immobilize the capture antibody by depositing 10 µL of anti-SARS-CoV-2 S1 antibody (6 µg/mL in PBS) onto the activated SPCE and incubate for 1 hour.

- Block non-specific sites by adding 10 µL of 1% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) solution and incubate for 30 minutes.

- Incubate the electrode with 10 µL of the sample containing the S1 protein antigen for 1 hour at 37°C.

- Form a sandwich complex by incubating with 10 µL of a secondary antibody solution for 1 hour, followed by incubation with 10 µL of Horseradish Peroxidase-labeled IgG (HRP-IgG) for 30 minutes.

- Wash the electrode thoroughly with PBS after each incubation step [27].

- 3. Amperometric Detection: Deposit 40 µL of 3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate onto the electrode and incubate for 3 minutes to allow the enzymatic reaction. Apply a constant potential of -0.1 V vs. the onboard Ag reference and record the current for 150 seconds. The reduction current of the oxidized TMB product is measured and is proportional to the S1 protein concentration [27].

Amperometric Measurement Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The performance of an amperometric sensor is highly dependent on the materials used in its construction. The following table catalogs key components and their functions in typical sensor development.

Table 2: Essential Materials for Amperometric Sensor Development

| Material/Reagent | Function in Experiment | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Screen-Printed Carbon Electrode (SPCE) | Disposable, miniaturized platform serving as the working electrode; provides a conductive carbon surface for immobilization. | Used as the base transducer for the SARS-CoV-2 S1 protein immunosensor [27]. |

| Fluorine-doped Tin Oxide (FTO) Electrode | A transparent, conductive substrate used as a base electrode, particularly useful when optical monitoring is also required. | Served as the substrate for NiCo₂O₄ nanoparticles in the hydroxylamine sensor [24]. |

| NiCo₂O₄ (NCO) Nanoparticles | Binary metal oxide nanozyme; acts as an electrocatalyst to lower the oxidation overpotential for the target analyte, enhancing sensitivity. | The key catalytic material for hydroxylamine oxidation [24]. |

| Glucose Oxidase (GOx) | Biological recognition element; an enzyme that specifically catalyzes the oxidation of glucose, providing high selectivity. | The biorecognition element in the amperometric glucose biosensor [23]. |

| Nafion Perfluorinated Resin | A cation-exchange polymer membrane; used to coat the electrode surface to prevent fouling and reject interfering anionic species. | Employed as a protective outer membrane in the glucose biosensor to enhance selectivity [23]. |

| EDC/NHS Crosslinkers | A carbodiimide-based coupling system; activates carboxyl groups on the electrode surface to facilitate covalent immobilization of biomolecules like antibodies. | Used to chemically activate the SPCE surface for antibody binding in the immunosensor [27]. |

| 3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) | An enzymatic substrate; used in conjunction with Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) label. The oxidized product is electrochemically detected at low potentials. | Served as the mediator for the HRP label in the sandwich immunosensor assay [27]. |

Amperometry stands as a powerful and versatile technique within the electrochemical toolkit. Its capacity for continuous, real-time monitoring at a constant potential, combined with high sensitivity and compatibility with miniaturized systems, makes it indispensable for modern analytical challenges. As demonstrated by its successful application in detecting diverse targets—from small molecules like hydroxylamine and glucose to complex proteins like SARS-CoV-2 S1—amperometry offers a reliable pathway for researchers and drug development professionals to obtain dynamic quantitative data. The ongoing development of novel materials, such as nanozymes and advanced electrode modifications, continues to push the boundaries of its sensitivity, selectivity, and application scope, ensuring its continued relevance in scientific research and industrial analysis.

Voltage Measurement and Ion-Selective Electrodes

Potentiometry is an electroanalytical technique that measures the electrical potential (voltage) between two electrodes under conditions of zero or negligible current flow. This method is fundamentally based on the Nernst equation, which describes the relationship between the measured potential and the activity (or concentration) of a specific ion in solution [28] [29]. The core principle involves using a potentiometer or high-impedance voltmeter to measure the potential difference between a reference electrode (which maintains a stable, known potential) and an indicator electrode (which responds to the activity of the target analyte) [28] [30].

Ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) represent the most significant application of potentiometry, serving as the indicator electrode that selectively responds to a particular ion species. These membrane-based devices convert the chemical activity of a specific ion dissolved in a solution into an electrical potential [28] [31]. The voltage produced is theoretically dependent on the logarithm of the ionic activity, as predicted by the Nernst equation [32] [31]. ISEs have revolutionized analytical chemistry by enabling rapid, selective measurements of ionic concentrations across diverse fields including clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, pharmaceutical analysis, and food safety [33] [34].

The development of ISEs has expanded the scope of potentiometric analysis beyond simple redox reactions. Since the discovery of the glass pH electrode in 1909 and subsequent development of membranes selective to other ions, potentiometry has evolved into a versatile technique capable of detecting numerous cations and anions with remarkable selectivity and sensitivity [29] [33]. Modern research continues to advance ISE technology through improved membrane materials, miniaturization, and integration with portable and wearable sensing platforms [33] [35].

Principles of Potentiometric Measurement

Fundamental Theory and the Nernst Equation

The theoretical foundation of potentiometry rests on the Nernst equation, which quantitatively relates the measured electrode potential to the activity of ions in solution. For a general redox reaction: ( aA + bB \rightleftharpoons cC + dD + ne^- ), the Nernst equation is expressed as:

[ E = E^0 - \frac{RT}{nF} \ln \frac{aC^c aD^d}{aA^a aB^b} ]

where:

- ( E ) is the measured electrode potential

- ( E^0 ) is the standard electrode potential

- ( R ) is the universal gas constant (8.314 J/mol·K)

- ( T ) is the temperature in Kelvin

- ( n ) is the number of electrons transferred in the redox reaction

- ( F ) is Faraday's constant (96,485 C/mol)

- ( a ) represents the activities of the species involved [28] [29]

For ion-selective electrodes, the simplified form of the Nernst equation for an ion ( I^{z+} ) with charge ( z ) is:

[ E = E^0 + \frac{2.303RT}{zF} \log a_I ]

At 25°C, this simplifies to ( E = E^0 + \frac{0.05916}{z} \log a_I ) volts, where the term ( \frac{0.05916}{z} ) represents the theoretical Nernstian slope per tenfold change in ion activity [28]. This logarithmic relationship means that ISEs can measure ion concentrations across several orders of magnitude with consistent relative precision.

Electrochemical Cell Configuration

A complete potentiometric measurement requires an electrochemical cell consisting of two half-cells:

- Indicator/Working Electrode: The ion-selective electrode whose potential varies with the activity of the target ion

- Reference Electrode: Maintains a stable, fixed potential independent of the solution composition [29]

The overall cell potential is measured as ( E{cell} = E{ise} - E{ref} ), where ( E{ise} ) includes the potential of the internal reference electrode and the boundary potential across the ion-selective membrane [31]. The reference electrode is typically a standard system such as silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl) or saturated calomel electrode (SCE), immersed in the same sample solution as the ISE [29] [31].

A critical requirement for accurate potentiometric measurements is the use of a high-impedance voltmeter that draws negligible current (typically < 1 pA) from the electrochemical cell. This prevents significant electrochemical reactions from occurring at the electrode surfaces and maintains the system at or near equilibrium conditions, ensuring that the measured potential relates directly to ion activities according to the Nernst equation [28] [29].

Ion-Selective Electrode Technology

ISE Components and Construction

Ion-selective electrodes share a common fundamental architecture regardless of the specific ion they detect. The key components include:

- Ion-Selective Membrane: The heart of the ISE, this component determines the electrode's selectivity and response characteristics. The membrane contains active sites that selectively interact with the target ion [28] [31].

- Internal Reference Electrode: Typically a Ag/AgCl wire immersed in a solution containing a fixed concentration of the target ion, providing a stable reference potential inside the electrode body [28] [32].

- Internal Filling Solution: Contains a known, constant concentration of the ion being measured, which contacts both the internal reference electrode and the inner surface of the ion-selective membrane [28].

- Electrode Body: Houses the internal components and provides structural integrity, often made of chemically resistant materials like glass or polymers [31].

In traditional ISE designs with liquid membranes, the internal solution serves as a bridge between the internal reference electrode and the ion-selective membrane. However, all-solid-state ISEs have gained prominence recently, where the internal solution is replaced by a solid contact material that acts as an ion-to-electron transducer [33] [34]. This design offers advantages including simplified construction, miniaturization potential, and resistance to pressure changes.

Types of Ion-Selective Membranes

The selectivity and performance of ISEs are primarily determined by the composition of the ion-selective membrane. Four main membrane types have been developed, each with distinct characteristics and applications:

Glass Membranes

- Composition: Silicate or chalcogenide glass with ion-exchange properties

- Selectivity: Primarily for single-charged cations (H+, Na+, Ag+)

- Applications: pH electrodes are the most common example

- Advantages: Excellent chemical durability, works in aggressive media

- Limitations: Limited to certain cations, exhibits alkaline and acid errors in extreme pH conditions [32] [31]

Crystalline Membranes

- Composition: Mono- or polycrystalline materials (e.g., LaF3 for fluoride ISE)

- Selectivity: For ions that can incorporate into the crystal lattice

- Applications: Fluoride detection, heavy metal monitoring

- Advantages: Excellent selectivity, no internal solution required

- Limitations: Limited to specific crystal-compatible ions [32] [31]

Liquid/Polymer Membranes

- Composition: Organic polymer matrix (typically PVC) plasticized with specific ionophores

- Selectivity: Determined by the incorporated ionophore; can be designed for numerous ions

- Applications: Most widespread ISE type, used for K+, Ca2+, NO3-, and many other ions

- Advantages: Versatile, can be tailored for many ions, well-characterized

- Limitations: Limited physical and chemical durability, potential for leaching [32] [31] [34]

Enzyme Electrodes

- Composition: Enzyme layer immobilized over a conventional ISE (often pH electrode)

- Mechanism: Enzyme reacts with specific substrate, producing a detectable product

- Applications: Glucose detection, biochemical sensing

- Advantages: Extends ISE capability to non-ionic analytes

- Limitations: Complex construction, limited enzyme stability [32] [31]

Table 1: Comparison of Ion-Selective Membrane Types

| Membrane Type | Selectivity | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glass | H+, Na+, Ag+ | pH measurement, sodium detection | High chemical durability, long lifetime | Limited to few cations, pH errors |

| Crystalline | F-, Cu2+, Cd2+, Pb2+ | Fluoride monitoring, heavy metals | Excellent selectivity, no internal solution | Limited to compatible crystal structures |

| Liquid/Polymer | K+, Ca2+, NO3-, Cl- | Clinical analysis, environmental monitoring | Highly versatile, tunable selectivity | Shorter lifespan, leaching potential |

| Enzyme-Based | Glucose, urea, neurotransmitters | Biomedical sensing, biochemical analysis | Extends to non-ionic analytes | Complex fabrication, enzyme stability |

Comparison with Other Electrochemical Techniques

Electrochemical analysis encompasses multiple techniques, each with distinct operating principles, capabilities, and limitations. Understanding how potentiometry compares with other major electrochemical methods is essential for selecting the appropriate analytical approach for specific applications.

Table 2: Comparison of Major Electrochemical Analysis Techniques

| Technique | Measured Quantity | Control Parameter | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potentiometry | Potential (voltage) | Zero current | pH, ion concentration (Na+, K+, Ca2+, F-, Cl-) | Simple, portable, wide concentration range | Moderate sensitivity, ionic interference |

| Voltammetry | Current | Applied potential | Trace metal analysis, organic compounds, reaction mechanisms | High sensitivity, qualitative & quantitative data | Requires supporting electrolyte, more complex |

| Amperometry | Current | Constant potential | Glucose biosensors, gas detection | High sensitivity, rapid response | Requires electroactive species, fouling issues |

| Coulometry | Total charge | Current or potential | Karl Fischer titration, quantitative analysis | Absolute method (no calibration), high accuracy | Long analysis times, requires complete reaction |

Potentiometry vs. Voltammetry The fundamental distinction lies in what is measured and under what conditions. Potentiometry measures potential at zero current, providing direct information about ion activities via the Nernst equation. In contrast, voltammetry applies a controlled potential and measures the resulting current, which provides information about redox properties and concentrations of electroactive species [30]. Potentiometry excels at direct ion activity measurements with simple instrumentation, while voltammetry offers higher sensitivity for trace analysis and capability for multi-analyte detection.

Potentiometry vs. Amperometry Amperometry measures current at a fixed applied potential, typically used for continuous monitoring of electroactive species. While amperometry provides superior sensitivity for certain applications (e.g., glucose monitoring), it requires the analyte to be electroactive at the applied potential. Potentiometry has wider applicability to non-electroactive ions and generally offers better selectivity through the ion-selective membrane [30].

Key Advantages of Potentiometry

- Simplicity: Instrumentation is straightforward and portable

- Wide concentration range: Typically 4-6 orders of magnitude

- Selectivity: Ion-selective membranes provide excellent discrimination

- Non-destructive: Minimal current flow preserves sample integrity

- Cost-effective: Inexpensive instrumentation and operation [32] [30] [34]

Limitations of Potentiometry

- Moderate sensitivity: Detection limits typically in micromolar range for conventional ISEs

- Ionic interference: Selectivity is not absolute, interfering ions can affect measurements

- Activity vs. concentration: Measures ion activity rather than direct concentration

- Drift and calibration: Requires frequent calibration for precise measurements [28] [31]

Recent advancements have addressed many limitations, with modern ISEs achieving nanomolar detection limits and improved selectivity through novel membrane materials and engineered ionophores [36] [33] [35].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Potentiometric Measurement Procedure

The following protocol outlines the general procedure for conducting potentiometric measurements with ion-selective electrodes, based on established methodologies from analytical chemistry literature [28] [29] [32]:

Equipment and Reagents

- Ion-selective electrode for target ion

- Appropriate reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl double junction)

- High-impedance pH/mV meter or potentiometer

- Magnetic stirrer and stir bars

- Standard solutions for calibration (minimum of 3 concentrations spanning expected range)

- Ionic strength adjustment buffer (if required)

- Deionized water for rinsing

Calibration Procedure

- Prepare standard solutions covering the concentration range of interest (typically 10-6 to 10-1 M or according to manufacturer's specifications).

- Immerse the ISE and reference electrode in the lowest concentration standard.

- Stir solutions gently and consistently throughout measurements.

- Record the potential (mV reading) once stable (typically 1-3 minutes, depending on electrode response time).

- Rinse electrodes with deionized water between measurements, blotting gently with laboratory tissue.

- Repeat steps 2-5 for all standard solutions in increasing concentration order.

- Plot potential (mV) versus logarithm of ion activity (or concentration) to obtain the calibration curve.

- Verify the slope is close to Nernstian (approximately 59/z mV per decade at 25°C).

Sample Measurement

- Calibrate the ISE as described above.

- Immerse electrodes in the sample solution (with ionic strength adjustment if necessary).

- Record the stable potential reading.

- Determine sample concentration from the calibration curve.

- For precise work, use the method of standard additions to account for matrix effects.

Quality Control

- Check electrode slope regularly (should be 95-102% of Nernstian)

- Perform duplicate measurements

- Monitor temperature and maintain consistency (±1°C for precise work)

- Store electrodes according to manufacturer recommendations

Advanced Experimental Approach: Temperature Pulse Potentiometry

Recent research has demonstrated innovative approaches to enhance ISE performance. The following protocol for Temperature Pulse Potentiometry (TPP) illustrates how thermal modulation can improve detection limits and measurement precision [35]:

Specialized Equipment

- All-solid-state ISE with integrated heating element

- Temperature controller capable of precise pulse generation

- Data acquisition system with high temporal resolution

- Custom electrode design with poly(3-octylthiophene) as intermediate layer

Experimental Workflow

- Fabricate solid-contact ISE with conducting polymer (POT) as ion-to-electron transducer.

- Deposit ion-selective membrane (e.g., copper-selective membrane with ionophore) over POT layer.

- Condition electrode in primary ion solution (e.g., 10-3 M Cu(NO3)2 for 24 hours).

- Implement temperature pulse protocol:

- Apply heating pulses (20-second duration) at specific intervals

- Follow with 50-second cooling periods

- Allow 2 minutes for potential stabilization between pulses

- Measure potential during heating and cooling cycles.

- Correlate potential changes with analyte concentration.

Key Findings and Advantages

- Heating pulses increase electrode slope (e.g., from 31 mV to 43 mV per decade for copper)

- Improved reproducibility (1% at 10 µM copper levels)

- Reduced detection limit by half an order of magnitude

- Lower potential drift (0.2 mV/h)

- Additional dimension for differential measurements [35]

This advanced methodology demonstrates how modified operation protocols can enhance conventional ISE performance, particularly for trace analysis applications.

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Successful potentiometric analysis requires specific materials and reagents optimized for each application. The following table outlines essential research reagents and their functions in ISE development and application.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Potentiometric Analysis with ISEs

| Reagent/Material | Function | Examples/Specific Types | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionophores | Selective ion recognition | Valinomycin (K+), BME-44 (Ca2+), tetracyclines (Cd2+) | Determine selectivity; often require co-immobilization with additives |

| Polymer Matrices | Membrane support matrix | PVC, polyurethanes, silicone rubbers | Affect diffusion coefficients and membrane stability |

| Plasticizers | Provide membrane mobility | o-NPOE, DOS, DBP | Influence dielectric constant and ionophore mobility |

| Lipophilic Additives | Counterion immobilization | NaTFPB, KTpClPB | Minimize anion interference in cation-selective electrodes |

| Ionic Strength Adjusters | Fix ionic background | NH4NO3, KNO3, NaCl | Eliminate variation in activity coefficients |

| Reference Electrode Fillers | Stable reference potential | 3M KCl, 1M LiOAc | Match sample ion mobility to minimize junction potentials |

Membrane Composition Guidelines Typical ion-selective membrane formulations include:

Recent Material Advances

- Conducting Polymers: Poly(3-octylthiophene), polyaniline as solid contacts [36] [33]

- Nanocomposites: Graphene, carbon nanotubes for enhanced conductivity [33]

- Novel Ionophores: Molecularly engineered carriers for specific ions [33] [34]

- Non-biofouling Materials: Poly(2-methyl-2-oxazoline)s for biological samples [36]

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The operational principle of ion-selective electrodes can be visualized as a sequential process involving several key stages from sample introduction to signal generation. The following diagram illustrates the signaling pathway and measurement workflow:

The experimental workflow for a complete potentiometric analysis involves multiple systematic stages, as illustrated in the following methodology flowchart:

Potentiometry with ion-selective electrodes represents a powerful analytical technique that combines theoretical elegance with practical utility. The method's foundation in the Nernst equation provides a robust theoretical framework, while ongoing advancements in membrane technology, electrode design, and measurement protocols continue to expand its capabilities.

When compared to other electrochemical techniques, potentiometry offers distinct advantages in simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and direct measurement of ionic activities. While methods like voltammetry may provide superior sensitivity for trace analysis of electroactive species, ISEs excel in selective determination of specific ions across wide concentration ranges with minimal sample preparation.

The development of all-solid-state ISEs, novel membrane materials, and advanced operation protocols like temperature pulse potentiometry are addressing traditional limitations and opening new application areas. These innovations, coupled with the inherent advantages of potentiometry, ensure that ISEs will remain indispensable tools in analytical chemistry, clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and pharmaceutical analysis.

As research continues to push the boundaries of detection limits, selectivity, and miniaturization, potentiometric methods are poised to play an increasingly important role in addressing analytical challenges across diverse scientific and industrial domains.

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) is a powerful, non-destructive diagnostic technique that resolves the kinetic and interfacial processes of electrochemical systems in the frequency domain [37]. Analysis typically relies on fitting data to equivalent circuit models (ECMs), but selecting the correct model is a significant challenge, as different models can yield deceptively similar spectra, complicating accurate representation of the underlying physics [38]. This guide objectively compares EIS against other common electrochemical detection techniques, highlighting its unique role in probing interface properties.

Comparative Analysis of Electrochemical Detection Techniques

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of EIS alongside other prevalent electrochemical methods, based on current research and application trends.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Electrochemical Detection Techniques

| Technique | Core Principle | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) | Measures system impedance across a frequency spectrum [37]. | Probing charge transfer, diffusion, and interfacial processes; biosensing; corrosion monitoring; energy storage materials [38] [37] [39]. | Label-free; non-destructive; provides rich information on interfacial properties and kinetics [37]. | Model selection is subjective and prone to error; analysis can be complex [38] [37]. |

| Voltammetry | Measures current as a function of applied potential. | Detection of heavy metal ions [5], cancer biomarkers [40] [41]. | High sensitivity; capable of simultaneous multi-analyte detection [5]. | Can be susceptible to electrode fouling; invasive as it alters the electrode surface. |

| Amperometry | Measures current at a constant potential. | Real-time monitoring; biosensing [40]. | Provides continuous data; high temporal resolution. | Provides less information on interfacial structure than EIS. |

Experimental Protocols: EIS in Practice

Standard EIS Measurement Protocol

A typical EIS experiment involves the following steps, which yield the data necessary for the comparisons in this guide:

- System Setup: A standard three-electrode system (working, reference, and counter electrode) is used. The experiment is conducted at the system's open circuit potential or under an applied DC bias [37] [39].

- Signal Application: A small-amplitude AC sinusoidal potential (typically 1-10 mV) is applied across a wide frequency range (e.g., 0.001 Hz to 105 Hz) [37] [42]. The small signal ensures the system response is pseudo-linear [42].

- Response Measurement: The resulting AC current signal is measured. In a linear system, this will be a sinusoid at the same frequency but shifted in phase [42].

- Impedance Calculation: The impedance, Z(ω), is calculated as the ratio of the voltage to current at each frequency and is expressed as a complex number: Z(ω) = Z' + jZ'', where Z' is the real part and Z'' is the imaginary part [42].

- Data Validation: The system must be at a steady state throughout the measurement to avoid drift. Data consistency can be checked using the Kramers-Kronig transformations [37].

Protocol for Automated ECM Selection

Traditional ECM selection relies on expert experience, making it subjective. The following automated, data-driven protocol addresses this limitation:

- Data Acquisition & Construction: Experimental EIS data is acquired. To ensure robust model training, this dataset is significantly augmented with simulated data designed to mimic electrochemical evolution by systematically varying parameters of relevant equivalent circuits [37].

- Initial Model Screening: A global heuristic search algorithm performs an initial screening of multiple potential ECMs [37].

- Error-Adaptive Optimization: An integrated classifier (e.g., based on XGBoost) uses multiple error metrics to dynamically adjust model weights, guiding an adaptive optimization for circuit classification [37].

- Parameter Estimation: After the optimal circuit is classified, a hybrid Differential Evolution–Levenberg–Marquardt (DE-LM) algorithm is used for precise parameter estimation. This combines a global search with local refinement [37].

- Validation: The fitted model is validated using dual-mode visualization (e.g., Nyquist and Bode plots) and a suite of error metrics (e.g., chi-square test, R²) [37].

This automated framework has demonstrated a model classification accuracy of 96.32% and a 72.3% reduction in parameter estimation error on a diverse dataset of 480,000 spectra [37].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of the automated EIS data interpretation process.

Diagram 1: Automated EIS Interpretation Workflow

The core of EIS analysis is modeling the electrochemical interface with an Equivalent Circuit Model (ECM). The foundational Randles circuit and a common modification are shown below.

Diagram 2: Key Equivalent Circuit Models for EIS

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for EIS

| Item | Function in EIS Experiments |

|---|---|

| Electrochemical Cell (3-electrode) | Standard setup consisting of a Working Electrode, Reference Electrode, and Counter Electrode for controlled potential application and current measurement [37]. |

| Redox Probe (e.g., [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻) | A well-characterized redox couple added to the solution to facilitate the charge transfer process, making it easier to monitor interfacial changes [37]. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | A common supporting electrolyte that maintains a constant ionic strength and pH, ensuring the electrochemical signal is dominated by the analyte of interest. |

| Nanomaterial-modified Electrodes | Electrodes functionalized with nanomaterials (e.g., CNTs, graphene, nanoparticles) to enhance sensitivity, selectivity, and signal amplification by increasing surface area and improving electron transfer [5] [40]. |

| Constant Phase Element (CPE) | A circuit model component used in place of a pure capacitor to more accurately represent the non-ideal, frequency-dependent capacitive behavior of real-world, heterogeneous electrode surfaces [37]. |

Advanced Applications in Biomarker and Pathogen Detection

The early detection of cancer is a pivotal factor in improving patient survival rates. Statistics indicate that cancers diagnosed at stage I have a five-year survival rate exceeding 90%, which declines sharply in advanced stages [40] [43]. Conventional diagnostic methods, including imaging techniques and tissue biopsies, are often limited by low sensitivity for early-stage tumors, high costs, and limited accessibility [44] [40]. Consequently, there is a pressing clinical need for diagnostic technologies that can detect trace levels of cancer biomarkers with high precision.

Electrochemical biosensors have emerged as powerful tools for this purpose, offering portability, cost-effectiveness, and rapid analysis [45] [46]. Their performance, particularly sensitivity and limit of detection (LOD), is profoundly enhanced by the integration of functional nanomaterials. These materials provide high surface areas, excellent electrical conductivity, and facile functionalization, which are critical for interfacing biological recognition events with efficient signal transduction [47] [46]. This guide objectively compares the performance of various nanomaterial-enhanced electrochemical techniques, providing a detailed analysis for researchers and drug development professionals.

Comparison of Electrochemical Detection Techniques

Electrochemical biosensors transduce biological recognition events into measurable electrical signals. The choice of detection technique significantly influences the sensor's sensitivity, specificity, and applicability. The table below compares the core electrochemical techniques used in conjunction with nanomaterials for cancer biomarker detection.

Table 1: Comparison of Electrochemical Detection Techniques for Cancer Biomarkers

| Technique | Measured Signal | Key Advantages | Reported Limits of Detection (LOD) | Common Biomarkers Detected |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | Current difference in pulsed potential | High sensitivity, low background current, rejects non-Faradaic currents | CA 125: 6 μU mL⁻¹ [47] [46] | PSA, CYFRA 21-1, CA 125, CEA [47] |

| Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) | Impedance (Resistance & Capacitance) | Label-free, real-time monitoring, studies binding kinetics and surface changes | NSE: 3 pg mL⁻¹ [46] | PSA, CEA, MUC1 [47] [40] |

| Amperometry | Current from redox reaction at constant potential | Simple, high signal-to-noise ratio, suitable for miniaturization | Not specified in results | Glucose, cholesterol, other metabolites [40] |

| Linear Sweep Voltammetry (LSV) | Current during linear potential sweep | Rapid screening, simple setup | Not specified in results | Carcinoembryonic Antigen (CEA) [47] |

The Role of Nanomaterials in Enhancing Sensor Performance

Nanomaterials are not merely passive supports; they actively enhance the analytical performance of biosensors. Their high surface-to-volume ratio increases the loading capacity of biorecognition elements (e.g., antibodies, aptamers), while their excellent electrical properties facilitate faster electron transfer, leading to signal amplification.

Table 2: Comparison of Nanomaterials Used in Electrochemical Biosensors

| Nanomaterial Class | Specific Examples | Key Properties | Impact on Biosensor Performance | Reported Experimental LOD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon-Based | Graphene, CNTs, rGO | High conductivity, large surface area, good biocompatibility | Signal amplification, enhanced stability, high biomolecule loading | NSE: 3 pg mL⁻¹ (Graphene/g-C₃N₄) [46] |

| Metal Nanoparticles | Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Excellent conductivity, biocompatibility, surface plasmon resonance | Facilitates electron transfer, acts as a platform for antibody immobilization | Various, in fM range [43] [48] |

| Composite Nanomaterials | AuNP/PEI/rGO, 3D rGO-MWCNT | Synergistic effects, combined properties of individual components | Superior sensitivity and stability compared to single-material sensors | CA 125: 6 μU mL⁻¹ [47] [46] |

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between nanomaterial properties and the resulting enhancements in biosensor performance.

Nanomaterial Enhancement Mechanism

Experimental Protocols for Key Setups

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for comparison, this section outlines detailed experimental protocols for two common and high-performance sensor configurations cited in the research.

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a Nanocomposite-based Immunosensor for CA-125 Detection

This protocol is adapted from studies describing ultra-sensitive detection of the ovarian cancer biomarker CA-125 [47] [46].

- Electrode Modification: A glassy carbon electrode (GCE) or screen-printed electrode (SPE) is used as the base platform. The electrode is polished with alumina slurry and thoroughly rinsed with deionized water.

- Nanocomposite Coating: A homogeneous suspension of a 3D reduced graphene oxide-multiwalled carbon nanotube (rGO-MWCNT) composite is prepared in a suitable solvent (e.g., DMF). A precise volume (e.g., 5-10 µL) of this suspension is drop-casted onto the clean electrode surface and allowed to dry, forming a highly conductive network.

- Immobilization of Capture Element: Polyamidoamine dendrimers stabilized with gold nanoparticles (PAMAM/AuNPs) are immobilized onto the nanocomposite-modified electrode. The AuNPs provide a biocompatible surface for the attachment of anti-CA-125 antibodies via covalent bonding or physical adsorption.

- Blocking: The electrode is treated with a blocking agent, such as bovine serum albumin (BSA), to cover any non-specific binding sites and minimize background signal.

- Detection and Signal Transduction: The sample containing CA-125 is introduced. For signal generation, a tracer label consisting of ortho-tolidine blue bonded to succinyl chitosan-coated magnetic nanoparticles is used. The electrochemical signal is measured using Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV), where the current response is proportional to the CA-125 concentration.

Protocol 2: Developing an Aptasensor for Biomarker Detection using EIS

This protocol outlines the creation of a label-free aptasensor, a common approach for detecting various cancer biomarkers [44] [46].

- Surface Functionalization: A gold disk electrode is cleaned and modified with a self-assembled monolayer (SAM) of thiolated molecules to create a well-ordered surface for biomolecule attachment.

- Aptamer Immobilization: Thiol-terminated DNA or RNA aptamers, selected for a specific cancer biomarker (e.g., PSA, MUC1), are incubated with the SAM-modified electrode. The thiol groups form strong Au-S bonds, covalently anchoring the aptamers to the surface.

- Blocking: The electrode is treated with a solution of 6-mercapto-1-hexanol (MCH) to passivate unoccupied gold sites and ensure the aptamer probes are upright, minimizing non-specific adsorption.

- Target Incubation: The functionalized electrode is incubated with the sample containing the target biomarker.

- Impedance Measurement: Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) is performed in a solution containing a redox probe (e.g., [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻). The binding of the target biomarker to the aptamer hinders electron transfer to the electrode surface, increasing the measured charge-transfer resistance (Rₑₜ). The change in Rₑₜ is correlated with the target concentration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful development of nanomaterial-enhanced biosensors relies on a specific set of reagents and materials. The following table details these key components and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Sensor Development

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable, portable, and mass-producible platform for electrochemical measurements; often made with carbon or gold working electrodes. | Used as a base for constructing a CA-125 immunosensor [46]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Act as excellent electron conductors and provide a stable surface for immobilizing biomolecules via thiol chemistry or electrostatic interactions. | Used in PAMAM/AuNP complexes for antibody immobilization [47] [48]. |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) & Reduced GO (rGO) | Provide a high-surface-area scaffold. GO's oxygen functional groups aid in dispersion and biomolecule attachment, while rGO offers superior conductivity. | Formed a 3D nanocomposite with MWCNTs to enhance sensor surface area and electron transfer [46]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs/SWCNTs) | Their high aspect ratio and conductivity facilitate electron transfer between the biorecognition element and the electrode. | Integrated with rGO to create a highly porous and conductive sensing layer [46]. |

| Specific Biorecognition Elements | Provide the high specificity required to identify and bind the target biomarker from a complex sample matrix. | Antibodies (for immunosensors) and aptamers (for aptasensors) against targets like PSA, CEA, and CA 125 [47] [44] [46]. |

| Electrochemical Redox Probes | Used in solution (e.g., for EIS) or as labels to generate or amplify the electrochemical signal. | [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ is commonly used in EIS. Ortho-tolidine blue was used as a tracer in a CA-125 sensor [47] [46]. |

The convergence of electrochemical detection techniques with nanomaterial science has unequivocally advanced the field of cancer biomarker detection. As demonstrated by the comparative data, nanomaterials such as graphene, carbon nanotubes, and gold nanoparticles can push detection limits to the picomolar range and beyond, offering sensitivities that surpass many conventional assays. Techniques like DPV and EIS, each with distinct advantages, provide researchers with versatile tools for developing both labeled and label-free sensing strategies.

While the performance metrics are promising, the successful translation of these technologies from research laboratories to clinical settings hinges on overcoming challenges related to manufacturing scalability, long-term stability, and rigorous validation using diverse clinical samples [40] [49]. Future research will likely focus on the intelligent design of multifunctional nanocomposites, the integration of AI for data analysis, and the development of standardized protocols to ensure reproducibility and reliability across the field.